Hybrid pythons could threaten beyond Florida Everglades

Pythons as long as SUV’s are tightening their grip on the Florida Everglades and with no natural predators in the state, the snakes native to Southeast Asia have quickly risen to the top of the food chain. A new study in the journal “Ecology and Evolution” suggests the python problem could slither beyond just the swamp

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. – With no natural predators in the Sunshine State, pythons native to Southeast Asia have taken over the Florida Everglades.

The slithering creatures killed off a large swath of native habitat when they became king of the Everglades, wreaking havoc on the system’s sensitive ecosystem.

But now experts say the python problem has slithered beyond the swamp and could impact ecosystems all across Florida. It’s unclear how far north the reptiles can go – the only conditions they seem to be susceptible to are colder climates – but experts worry they could easily adapt and invade other parts of the state.

“We set out to investigate the Burmese python in the Everglades to help provide information for management and conservation agencies…we found 13 of the 400 snakes that we analyzed had portions of Indian python within their genome,” said Margaret Hunter, a USGS geneticist and the lead author of a study by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in the journal Ecology and Evolution, which concluded the snakes will become a growing problem in the U.S.

Unlike the marsh-loving Burmese python, the Indian python prefers a high, drier habitat.

“This might allow this population to expand into drier environments…maybe further to the north or outside of the Everglades…where the population is right now,” Hunter said.

She said more research needs to be done to determine when the hybridization of the two python species occurred, but there are three likely scenarios: they could have crossed in their native Southeast Asia, in the pet trade or after arriving in the Everglades.

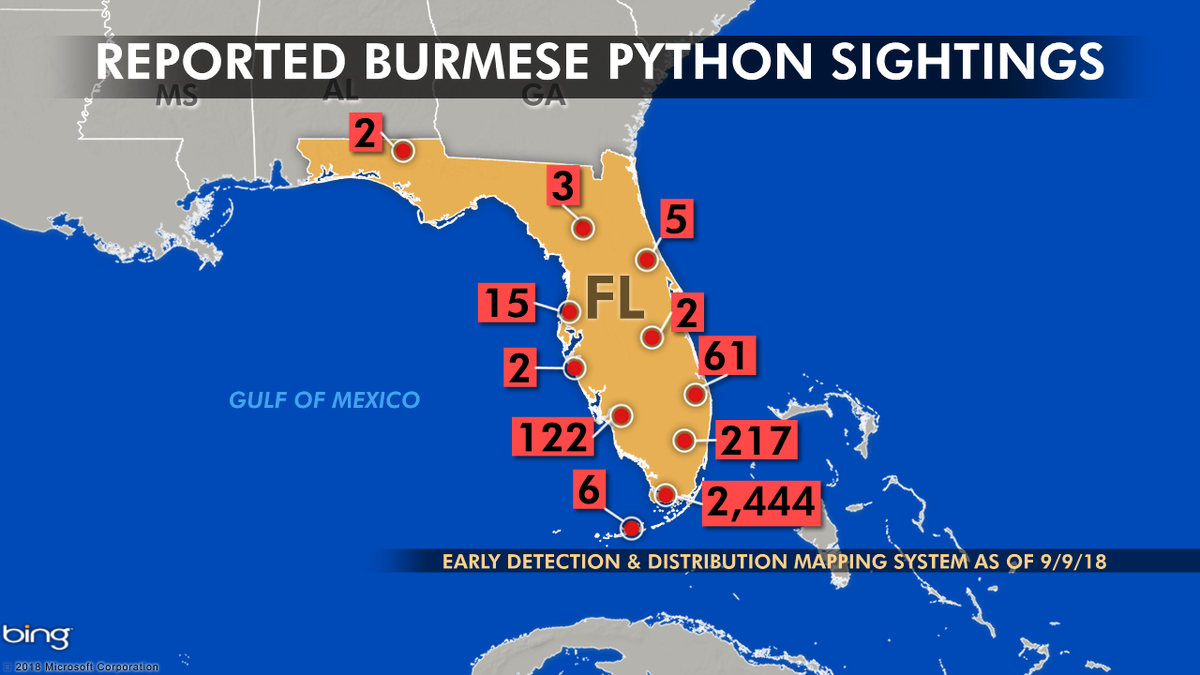

Researchers say it is difficult to determine whether python sightings north of the Florida Everglades are a result of migration or pet releases. (Fox News)

But no matter how the species developed, one thing is certain: If the pythons expand beyond the Everglades, it would upend the state’s entire ecosystem.

“There has been evidence of severe small mammal declines linked to the Burmese python invasion in South Florida,” Hunter said. “Presumably, this trend could continue if the python population expands to the north.”

Experts are hoping that the animals would not survive colder climates, but the adaptability of the snakes has them concerned.

“The only thing we can hope for is to have cold snaps come through, that’s the only thing that’s been shown to throw the population back, but it also kills a ton of our native animals,” said Chris Gillette, an animal expert at Everglades Holiday Park in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “As you go north, there are also a lot more burrowing animals like gopher tortoises and armadillos and the pythons will utilize their burrows to avoid the cold. So, as they continue expanding north, it’s going to be real interesting to see how this plays out.”

Python hatchlings were first found in Everglades National Park in the 1980s. Today, they’ve turned into what scientists consider Florida’s largest invasive species, killing off huge numbers of animal life native to the Everglades.

“We’ve seen that these pythons can remove 90 percent or greater of the mammals throughout the Everglades,” Hunter said. “So, we’re quite concerned about the populations of these animals in South Florida potentially leading to local extinctions of these populations.”

“Marsh rabbits are the first to go, rats, cotton tail rabbits, raccoons, possums…,” said python hunter Tom Rahill.

The South Florida Water Management District's Python Elimination Program has brought in over one thousand snakes. The largest recorded was a whopping 18 feet long. (Associated Press)

Even deer and alligators have been found in the stomach of the silent predator.

According to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, approximately 99,000 Burmese pythons were imported to the U.S. between 1996 and 2006. In 2012, all constrictor snakes were banned from importation into the U.S. and interstate commerce of the animals was also made illegal.

Up to 100,000 pythons are believed to be creeping through Florida’s wetlands, most of them descendants of pets illegally released into the wild after getting too big and dangerous for their owners. A Burmese python can reach an impressive 23 feet long and weigh up to 200 pounds, growing from a 20-inch hatchling into an eight-foot predator in just one year.

Because of their wide dietary preferences, long lifespan of 15 to 25 years, high reproductive output, and impressive swimming abilities, the snakes have been able to thrive in South Florida, using the region’s widespread and elaborate canal systems to spread across the state.

State and federal wildlife managers have tried all available options to combat the problem: tracking the snakes with dogs, using traps, fitting snakes with radio trackers, public hunting contests and even using what scientists call “Judas snakes” to lead them to other pythons.

Last year, the South Florida Water Management District created the Python Elimination Program, hiring 25 licensed contractors to hunt and kill the invasive predators known to be so cryptic, you could be “standing right on top of one and not even know it,” said Rahill, who founded a non-profit called “Swamp Apes” and takes war veterans out python hunting with him to help them cope with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

The wranglers are paid $8 per hour to drive, hike and probe through the hot and humid Everglades looking for the well-camouflaged constrictors, receiving $50 for every snake killed and an extra $25 for every foot longer than four. A pregnant python rakes in an additional $100.

“Once you make contact, it’s game on…it’s an incredibly invigorating adrenaline-pumping experience,” said Rahill. “These will never be eliminated, unfortunately, but the pythons have to be managed.”