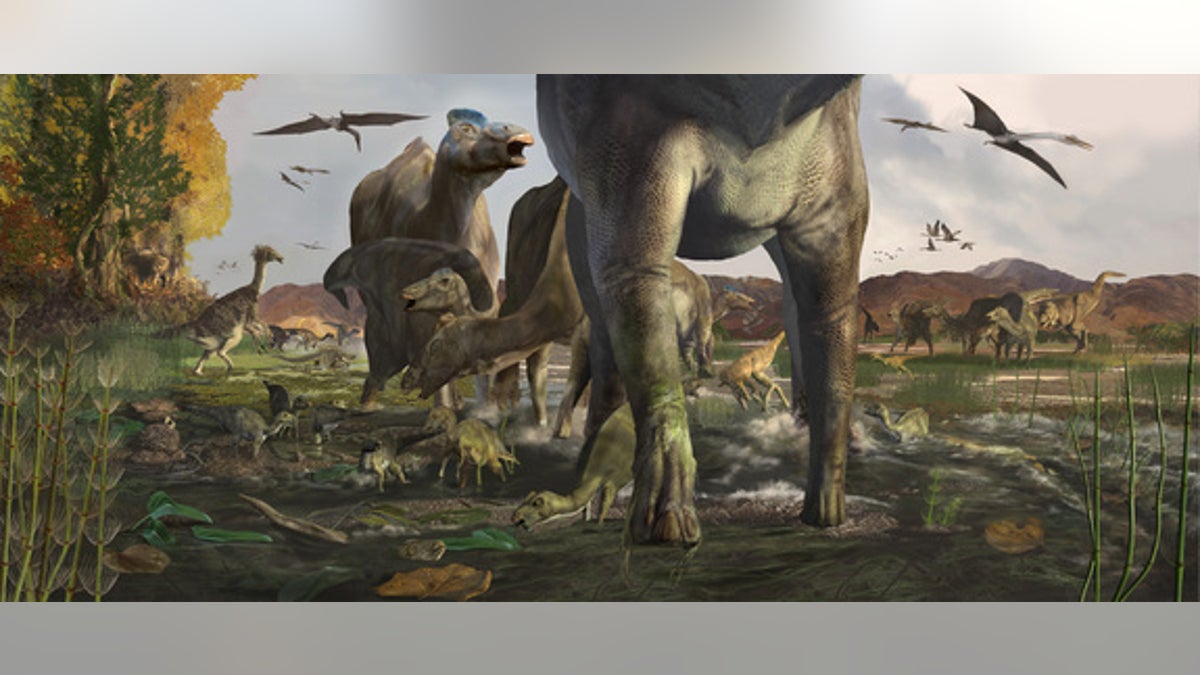

Artist's conception of how the trace fossils were formed roughly 70 million years ago. (Karen Carr/Perot Museum)

A "world-class" dinosaur track site discovered in Alaska's Denali National Park shows that herds of duck-billed dinosaurs thrived under the midnight sun.

"We had mom, dad, big brother, big sister and little babies all running around together," said paleontologist Anthony Fiorillo, who is studying the dinosaur tracks. "As I like to tell the park, Denali was a family destination for millions of years, and now we've got the fossil evidence for it."

The discovery adds to Fiorillo's growing conviction that dinosaurs lived at polar latitudes year-round during the Late Cretaceous Period, about 70 million years ago. [Images: Denali National Park's Amazing Dinosaur Tracks]

"Even back then the high latitudes were biologically productive and could support big herds of pretty big animals," said Fiorillo, curator of earth sciences at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas.

Dino dance party

The dinosaur track site, near Cabin Peak in the park's northeast corner, has thousands of tracks from hadrosaurs, or duck-billed dinosaurs. Many of the deep tracks contain preserved skin and "nail" impressions from the plant-eating hadrosaurs.

"This is definitely one of the great track sites of the world. We were so happy to find it," Fiorillo said.

Fiorillo and his collaborators also found traces from birds, clams, worms and bugs intermingled with the dinosaur tracks. Other dinosaur denizens who left behind footprints in Denali were ceratopsians, therizinosaurs and the flying reptiles called pterosaurs. Ferns and redwood cones complete the picture of a rich Cretaceous ecosystem.

The muddy ground is so rumpled by footprints that the researchers were hard-pressed to pull out tracks from individual hadrosaurs. Instead, they counted each print and grouped them by size. The results were published June 30 in the journal Geology.

There are four distinct size ranges, varying in length from 5 inches to 24 inches. More than 80 percent of the tracks are from adults, and 13 percent are from young duckbills less than a year old. Just 3 percent are juvenile hadrosaurs. The researchers think the small number of juvenile prints suggest the young underwent a rapid growth spurt, spending only a short time as tiny, vulnerable dinosaurs (a theory also supported by studies of hadrosaur bones).

Duck-billed dinosaurs are the most common dinosaur fossils from the Late Cretaceous, with a wide range of species found on several continents. Call them the buffalo of the dinosaurs, grazing on the fern prairie and protecting their young in big herds.

Polar patrol

The evidence emerging from the Denali hadrosaur tracks show babies and juvenile dinosaurs living in Alaska during the summer. The juveniles probably couldn't endure a long migration, so the tracks suggest the dinosaurs spent their entire lives in the Arctic, rather than migrating from somewhere else, the researchers said.

Some researchers have speculated that dinosaurs migrated north to Alaska, perhaps even coming from Canada like huge caribou herds.

"If you take a great big herd of plains eaters, they have to move at some level, otherwise they strip out all the vegetation," Fiorillo said. "But there's a growing data set that suggests they didn't do the thousand and thousands of miles of migration that was originally considered."

During the Late Cretaceous, Alaska sat at about the same latitude as today, but it was a tectonic jigsaw puzzle that had yet to assemble into today's stunning topography. Mountain-fed rivers and streams flowed through Denali, but not the same mountains: the Alaska Range was just being born. Mount McKinley, now the tallest mountain in North America, didn't exist. The climate was warmer, similar to coastal Washington and Oregon, but sunlight still flipped between extremes, with lengthy summer days and long, dark winters. [In Images: How North America Grew as a Continent]

Despite the dark winters, scientists such as Fiorillo have uncovered scores of dinosaur fossils and tracks across Alaska in recent decades, from quarries near the North Slope oil fields down to Denali's spectacular mountains.

Preserving history

Fiorillo and colleagues from Texas, Japan and Alaska have been documenting the new Denali track site since 2011. Exhibits featuring copies of the Denali dinosaur fossils and hadrosaur footprints are on display in the park and at the Perot Museum in Texas.

The trampled ground sits at the top of a steep ridge and is exposed on a cliff face about 590 feet long. The tracks were made within a short time range, between 69 million to 72 million years ago, likely in a muddy river or stream bank during the height of summer, the researchers said. (The bugs and plants help pin down the time of year.)

The outcrop was revealed by a rockfall and could be destroyed by another landslide in the future, so researchers scanned the area with lidar (a high-resolution laser-scanning technique) to preserve the site forever.

"On one of the last nights, as work was coming to a close, I was lying in my tent and woke up to an earthquake in the park," Fiorillo said. "For the first time in my life, I wasn't worried about a big rock [hitting me]. I was worried about my track site sliding down the mountain."