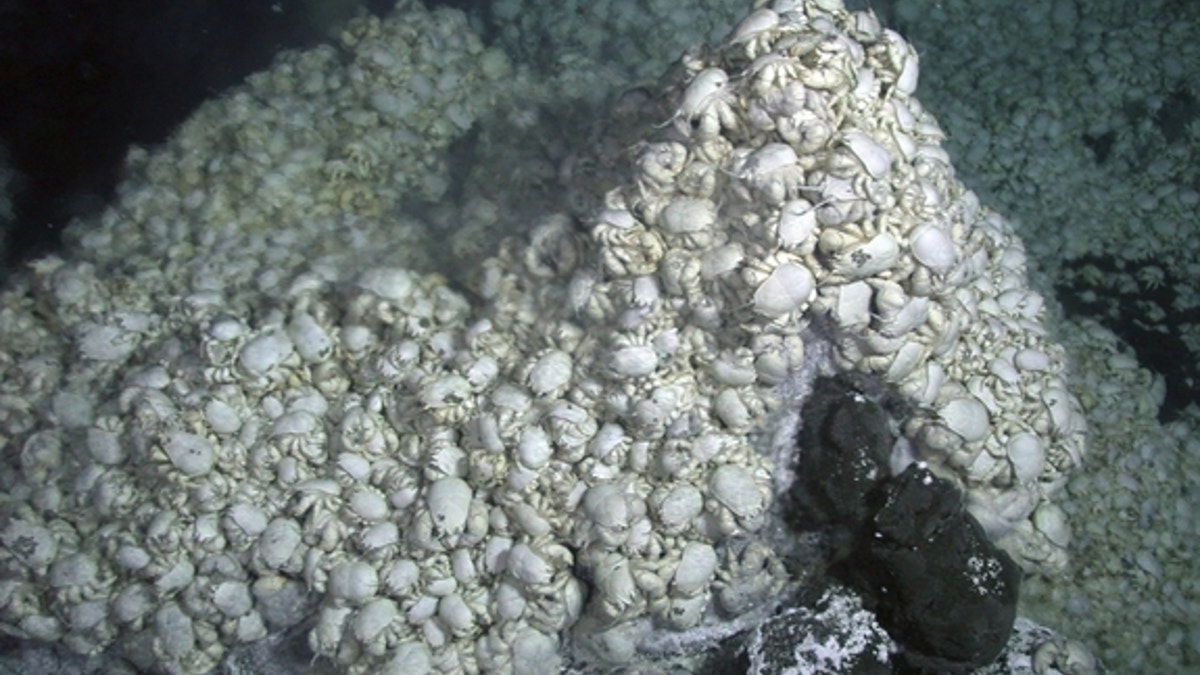

‘Hoff’ yeti crabs around vents on the East Scotia Ridge in the Southern Ocean. (CHESSO consortium)

Yeti crabs don't comb their hair to look good they do it because they're hungry.

These bizarre deep-sea animals grow their food in their own hair, trapping bacteria and letting it flourish there before "combing" it out and slurping it up. The crabs are found near cold seeps and hydrothermal vents, places where mineral-rich water spews out of the seafloor.

Like many animals that live in these extreme environments, yeti crabs have been thought of as "living fossils," largely isolated from the rest of world and, therefore, unchanged for eons. But new research shows these animals actually evolved relatively recently, suggesting the deep-sea environments the crabs call home may be more changeable than previously thought and more vulnerable to shifts in the atmosphere and climate, said Oxford University researcher Nicolai Roterman. [See Images of Yeti Crabs & Bizarre Deep-Sea Creatures]

A study by Roterman and his colleagues detailing the evolutionary history of these bizarre creatures was published June 18 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, and their research turned up a few surprises.

Whence the yeti crab?

Scientists have officially described four species of yeti crabs, the first of which was found in 2005, and all of which sport furry claws. Three years ago, however, Roterman helped discover another crab in the same family near the East Scotia Ridge in the Southern Ocean; it features a hairy chest on which the animal "farms" its own food, Roterman told LiveScience. Upon helping to discover the crab, Roterman nicknamed it the "Hoff" crab, after the shaggy-chested actor David Hasselhoff. "It was the first name that popped into my head," Roterman said. "And it stuck."

Roterman and co-authors found that these crabs are most closely related to squat lobsters, relatively common animals that live among deep-sea corals in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The researchers' analysis of the different species' DNA suggests the crabs arose in the eastern Pacific and then migrated west, extending their range into the Indian Ocean. Each of the yeti crab species shares a common ancestor that lived about 35 million to 40 million years ago, more recently than previously thought, Roterman said.

All but one of these yeti crab species live at hydrothermal vents, where water rocketing out of the Earth can reach temperatures of 716 degrees Fahrenheit. The crabs lead a perilous life, getting as close to the steaming water as possible to bathe their whisker-hugging microbes in the water's nourishing chemicals. If the crabs get too close, however, they can be cooked alive.

More vulnerable than thought

The other species of yeti crab lives around methane seeps off of Costa Rica, and is named Kiwa puravida (the species name meaning "pure life," the Costa Rican motto). Genetic evidence suggests this species branched off from its family's common ancestors before the others, meaning that yeti crabs may have first evolved in these relatively less-extreme environments and later migrated to hot hydrothermal vents, Roterman said.

The crabs may also be more vulnerable than previously thought. These creatures make do with extremely low levels of oxygen, surviving at the limits that can sustain life, Roterman said. Oxygen arrives at these remote locations from the surface, making its way to the deep ocean after cold water has sunk at the poles and moved toward the equator.

The ocean's circulation is sensitive to long-term increases in temperature, however. Studies have shown that the atmosphere greatly warmed and deepwater oxygen decreased significantly about 55 million years ago, possibly killing off animals that lived at hydrothermal vents at the time. Their demise, in turn, cleared the way for the yeti crabs to evolve and take over their current niche, Roterman said.

"I'm not suggesting these animals are going to be imminently effected by climate change, but that they are not completely immune to what happens at the surface," he said.

"The number of knownKiwa species still is small, but [this] study conducts a competent phylogenetic analysis based on DNA sequence data," said Robert Vrijenhoek, a scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute who discovered the first yeti crab in a 2005 expedition in the southeastern Pacific near Easter Island.

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.