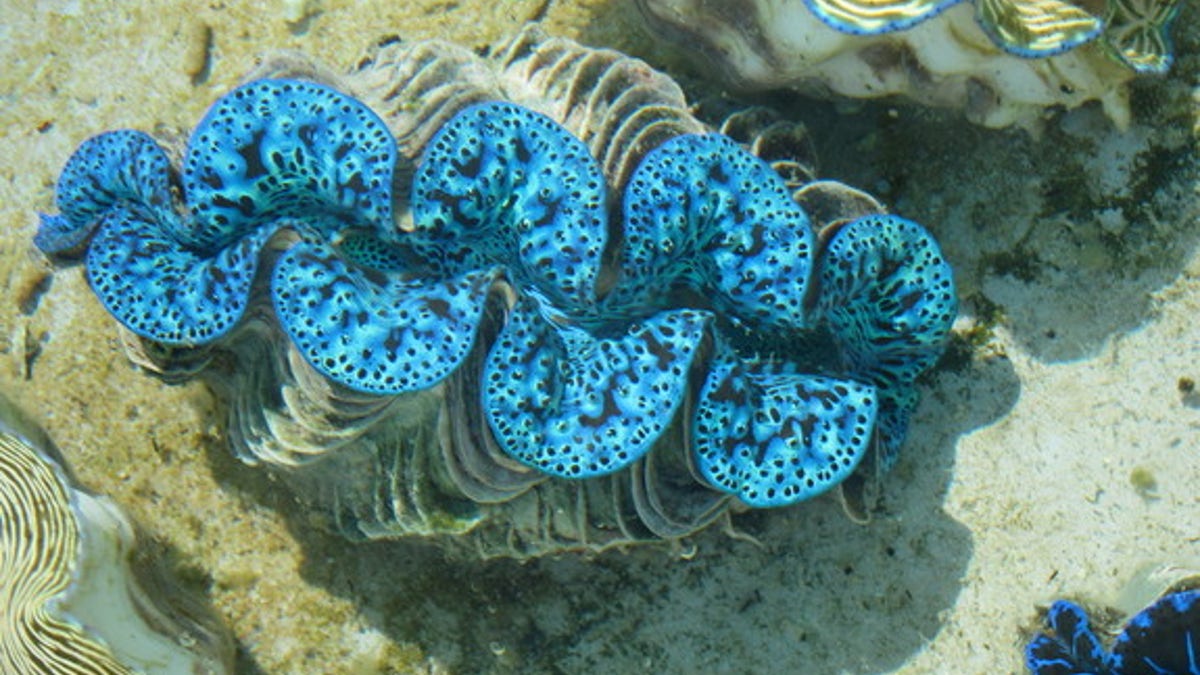

The brilliant blue reflective cells on a giant clam can reflect sunlight for algae living inside its shell. (Dan Morse)

Brilliant shades of blue and aqua coat the iridescent lips of giant clams, but these shiny cells aren't just for show, new research finds. The iridescent sheen directs beams of sunlight into the interior of the clam, providing light for algae housed inside.

In a symbiotic return, the algae use that sunlight to power photosynthesis, resulting in energy for the giant clam. "It ends up being a large part of the energy budget of the clams," said study researcher Alison Sweeney, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania.

Essentially, the oversize mollusks, which can measure more than 4 feet long, have a natural solar energy system hiding in their shells.

Most iridescent cells including those that impart a vivid blue to the morpho butterfly, the glittery colors of beetles and the shine of birds' feathers are dead, much like fingernails and human hair. But the iridescent cells of squid and giant clams are alive. [Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures]

So, the researchers wondered, "What on Earth is a giant clam doing with a living iridescent cell?" Sweeney said.

Giant clams have a dull outer shell, as well as a weighted shell hinge that helps them point their lips up toward the sunlight. Perhaps the iridescent cells, called iridocytes, play an optical function, the researchers reasoned.

The team traveled to Palau, an island east of the Philippines in the tropical Pacific Ocean, to gather information about the giant clams. "We put this into a computer model about how we think light propagates through the clams," Sweeney said. "[But] nobody actually believed it," she added, referring to how the light was reflected back into the shells of the clams.

So, they returned to Palau to take detailed measurements of light inside the clams Tridacna derasa, T. maxima and T. crocea with the help of a fiber-optic probe. The iridescent cells reflected a remarkable amount of light into the clam, more than the scientists had initially expected, Sweeney said. Clam tissue with iridocytes has about fivefold more particles of light, called photons, deep inside the tissue than clam tissue without iridocytes does, they found.

"We're very excited by our surprising discovery," said study researcher Dan Morse, a professor of biomolecular science and engineering, and director of the Marine Biotechnology Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

"The brilliantly reflective cells of the giant clam actually redirect photons from sunlight deeper into the clam's tissue, gently and uniformly illuminating millions of symbiotic algae that live there, so they can provide nutrients to their animal host by photosynthesis," Morse wrote in an email to Live Science.

The algae's configuration is also efficient, the researchers found. If the algae were spread horizontally across the clam's tissue, only the top layers of algae would get light. The giant clam, however, doesn't have this obstacle. Instead, the algae are piled into vertical columns that allow the reflective cells to shine light along the sides of the columns not just the algae on top.

The reflected light is also less intense than direct sunlight, so the algae don't get fried, Sweeney said.

The study is "very interesting," Euichi Hirose, a professor of invertebrate biology at the University of the Ryukyus in Japan, told Live Science in an email.

"Now, we know the giant-clam mantle has a more sophisticated function than we expected," said Hirose, who was not involved in the current study. "The colorful mantle reflects useless light for photosynthesis (green and yellow) and scatters useful light (red and blue) forward, and laterally,into deep tissue."

The giant clams' colorful and sparkly sheen may one day inspire new forms of clean technology, the researchers said. For instance, traditional solar cells work well in direct sunlight, but not when they get too hot. With the clam's design, a reflective sheen could help solar cells stay cool even when they're exposed to intense sunlight, Sweeney said.

The study was published Sept. 30 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.