Survivor of last American slave ship identified

Dr. Hannah Durkin of the U.K.'s University of Newcastle has determined the identity of the last survivor of the last American slave ship. Redoshi, given the slave name 'Sally Smith,' was kidnapped from West Africa at age 12 and, after spending five years as a slave, died in Alabama in 1937 at the age of 89 or 90. Previously, the last survivor of the transatlantic slave trade was thought to be Oluale Kossola, also known as Cudjo Lewis, who died in 1935.

After painstaking research, the final survivor of the last American slave ship has been identified.

An expert from the U.K.’s University of Newcastle carefully pieced together the life of Redoshi, from her kidnapping as a child in West Africa, to her enslavement in Alabama and, eventually, her freedom.

Redoshi was one of 116 children and young people taken from West Africa in 1860 on board the Clotilda, the last American slave ship, according to Dr. Hannah Durkin, lecturer in Literature and Film in Newcastle University’s School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics. Given the slave name Sally Smith, Redoshi died in Alabama in 1937.

Previously, the last survivor of the Clotilda was thought to be Oluale Kossola, also known as Cudjo Lewis, who died in 1935.

Redoshi, described as "Aunt Sally Smith," appeared briefly in a 1930s public information film entitled “the Negro Farmer” that was produced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. (U.S. Department of Agriculture/National Archives)

The BBC reports that Redoshi, who was kidnapped at age 12, was about 89 or 90 at the time of her death in Selma, Alabama.

Durkin’s research sheds new light on Redoshi’s life. After arriving in the U.S., she was purchased by Washington Smith, owner of the Bogue Chitto plantation in Dallas County, Alabama and a founder of the Bank of Selma.

A GLIMPSE INTO HISTORY: PHOTO OF YOUNG HARRIET TUBMAN SURFACES

A slave for nearly 5 years, Redoshi worked both in the Bogue Chitto plantation house and in the fields, according to the research. She married a fellow slave known as William or Billy, whom she had been kidnapped with. Her husband died in the 1910s or 1920s.

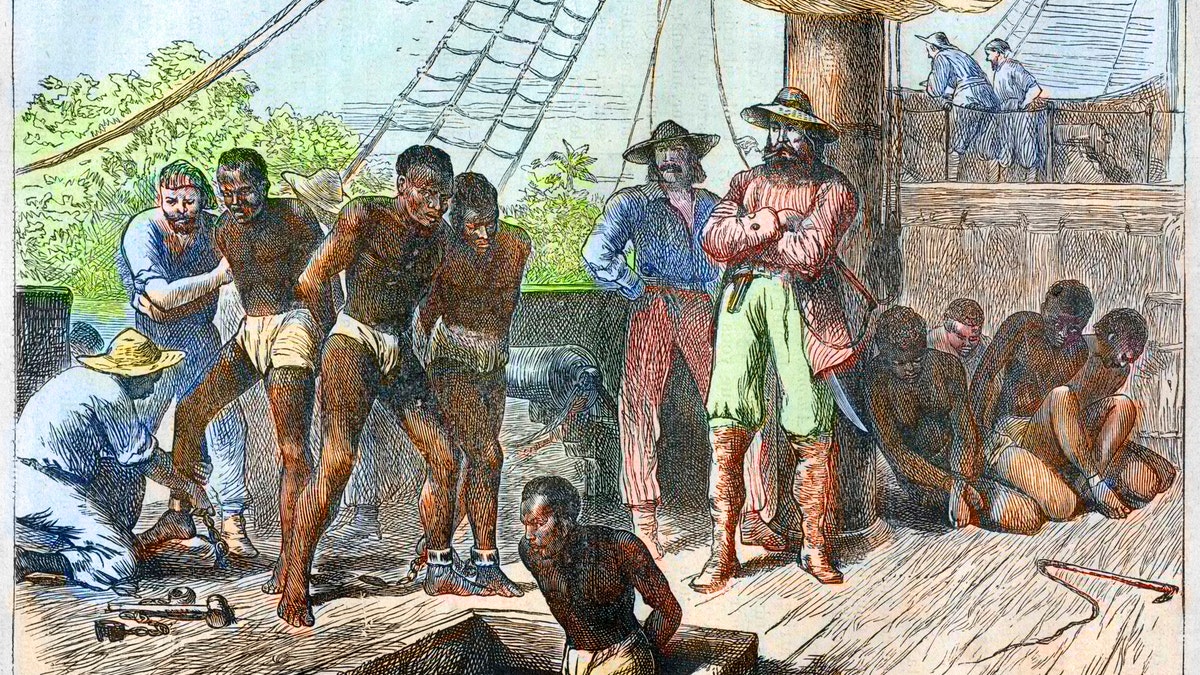

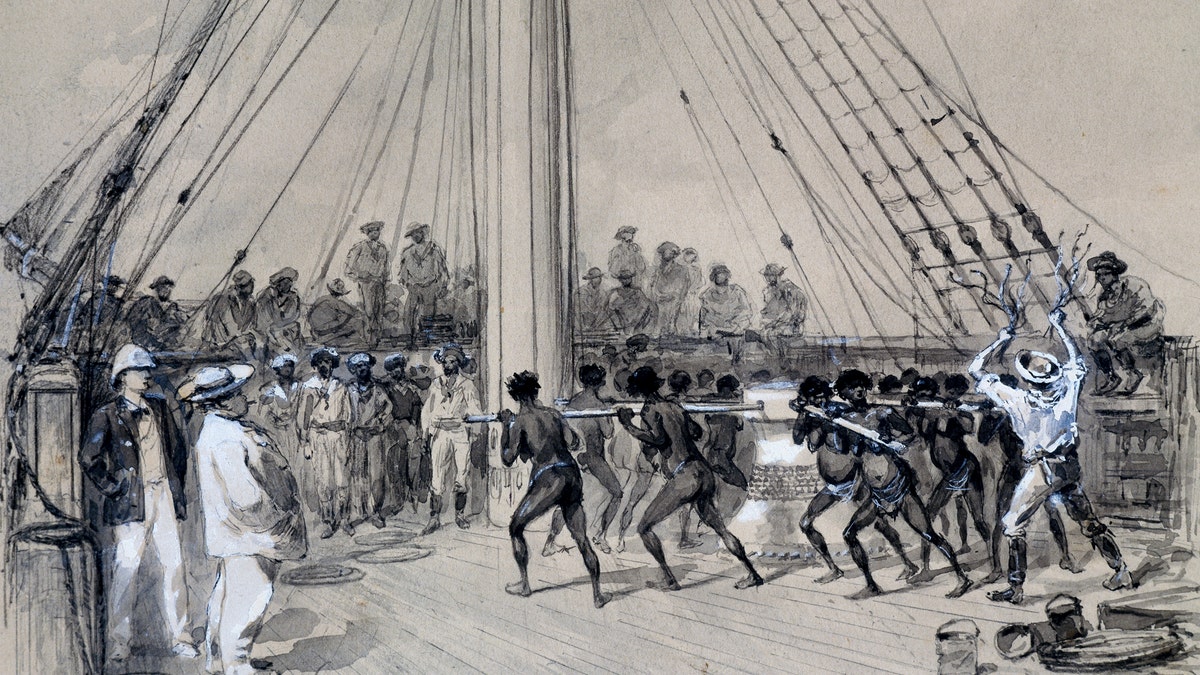

African slaves being taken on board ship bound for USA - engraving 1881. (Photo by Stefano Bianchetti/Corbis via Getty Images)

After her emancipation, Redoshi continued to live on the Bogue Chitto plantation with her daughter.

Durkin found out about Redoshi while conducting other research. The former slave was mentioned in the writings of famous author Zora Neale Hurston; Durkin also found references in other texts, including a newspaper article and a memoir by civil rights activist Amelia Boynton Robinson. In her book, Boynton Robinson recalls Redoshi, writing that she was forced to become a child bride on the Clotilda.

TEXAS CONSTRUCTION WORKERS DISCOVER REMAINS OF 95 AFRICAN-AMERICAN LABORERS FROM EARLY 20TH CENTURY

Redoshi also appears briefly in a 1930s public information film entitled “the Negro Farmer” that was produced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In the film, she is described as “Aunt Sally Smith, born in Africa and long past her 110th year when she died in 1937.” Durkin believes that this description of Redoshi’s age is likely an exaggeration.

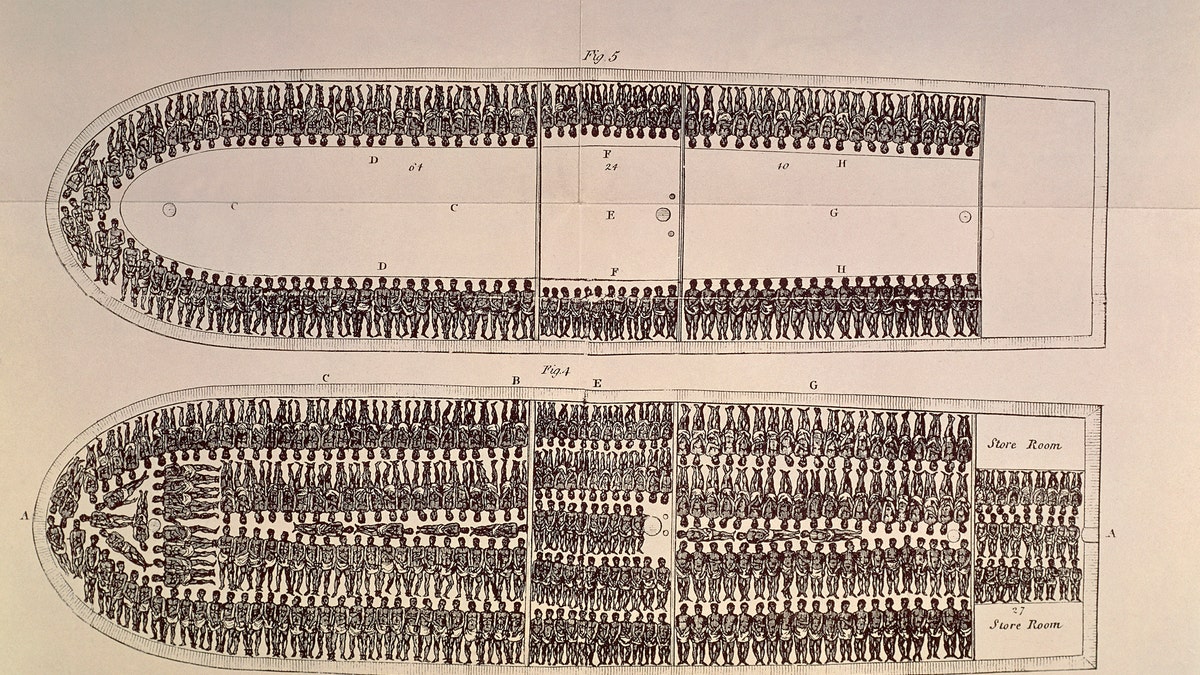

Positioning of slaves on a slave ship, 1786, illustration from Abolition of the slavetrade, 1808, London. Slavery, England, 18th century. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Her research into Redoshi’s life is published in the journal Slavery and Abolition.

“The discovery increases our understanding of the slave trade because it gives meaningful voice to a female survivor for the first time,” Dr. Durkin told Fox News, via email. “We can now begin to reflect on what transatlantic slavery and its aftermath was like for an individual woman.”

RARE POWDER HORN THAT BELONGED TO AFRICAN AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR SOLDIER GOES ON DISPLAY

Part of the triangular trade in slaves and goods between Africa, the Americas and Europe, the transatlantic transport of slaves is known as the Middle Passage. Between the 16th and the 19th centuries, around 12 million African slaves were shipped to the Americas, according to the Boston African American National Historical Site. About 15 percent of slaves died during the horrific voyages, which lasted around 80 days.

A detail view of a length of chain in the museum aboard the Tall ship Kaskelot, a replica of the 18th century wooden square rigger ship 'The Zong', on the River Thames by Tower Bridge on March 29, 2007 in London, England. (Photo by Bruno Vincent/Getty Images)

“What is shocking is that we now know that the trauma of the Middle Passage as a lived experience did not end until 1937, so only really 80 years ago,” Durkin told Fox News.

Durkin notes that, while Redoshi lived through tremendous trauma and separation, there is a sense of pride in the texts that describe her. “Her resistance, either through her effort to own her own land in America or in smaller acts like keeping her West African beliefs alive, taking care in her appearance and her home and the joy she took in meeting a fellow African in the 1930s, help to show who she was,” she explained in a statement.

ARCHAEOLOGISTS UNCOVER HISTORY IN SOUTH CAROLINA BACKYARD

Last year, it was reported that the remains of the Clotilda may have been found in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, Alabama. The notorious ship was set ablaze after delivering its captive cargo from Benin in West Africa to Mobile. Subsequent analysis, however, revealed that the wreckage does not belong to the Clotilda.

African slaves working the winch on a ship, watercolour by Edouard Riou (1833-1900). Paris, Musée National Des Arts Africains Et Oceaniens (Art Museum) (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Archaeologists in Delaware recently discovered the gravestone of a Civil War soldier that may provide a vital clue in uncovering a long-lost African-American cemetery.

Experts working at a property near Frankford, Sussex County, found the headstone bearing the name “C.S. Hall” and the details “Co. K, 32nd U.S.C.T.” This refers to Company K of the 32nd U.S. Colored Troops, which was a designation for African-American soldiers, according to Delaware’s Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The site is known to the local community as containing the remains of African-Americans that lived in the area, officials say. In February, officials said that the remains of slaves have not yet been confirmed at the site, either through archaeological excavation or analysis of historical records.

Fox News’ Chris Ciaccia contributed to this article. Follow James Rogers on Twitter @jamesjrogers