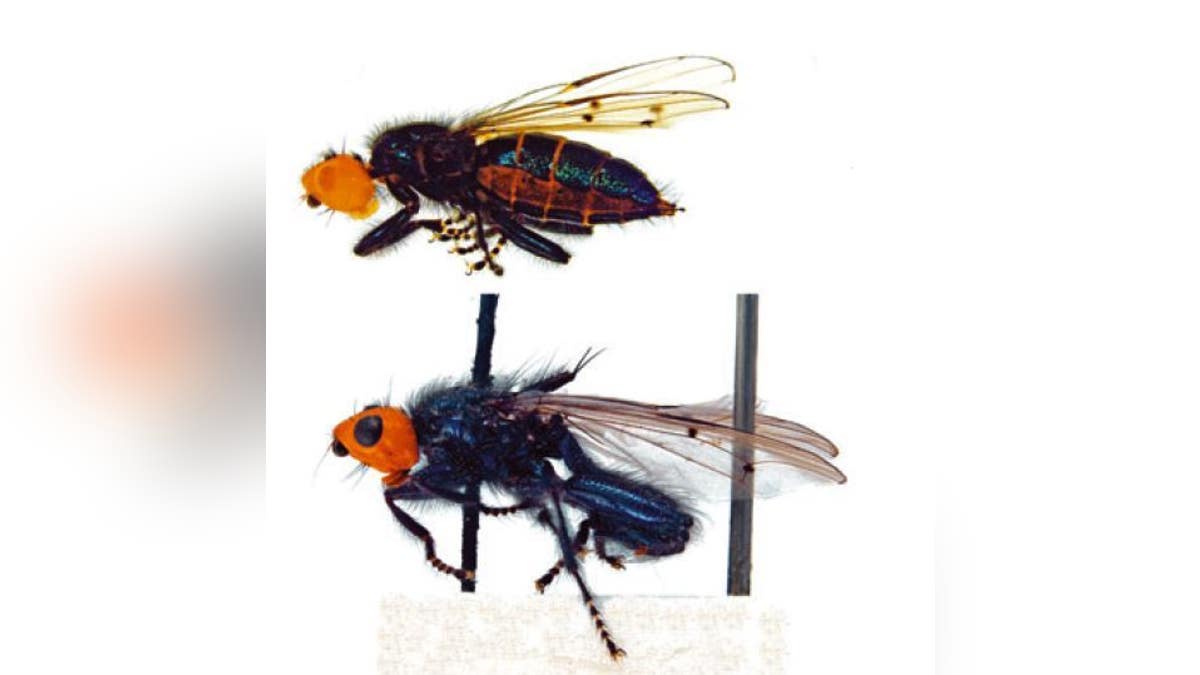

A species of bone-skipper, Thyreophora cynophila, which was first discovered in Mannheim, Germany, in 1798. They had been thought to be extinct for about 160 years before being found again in Spain in 2010. Top: female fly. Bottom: male. (Daniel Martin-Vega / Systematic Entomology)

Behold the bone-skipper, high in the running for the strangest fly on Earth. For the bone-skipper, fresh carcasses just won't do. No, these flies prefer large, dead bodies in advanced stages of decay. And unlike most flies, they are active in early winter, from November to January, usually after dark.

They also disappeared from human notice and were declared extinct for more than a century. That's why they've often been considered almost mythical or legendary, said Pierfilippo Cerretti, a researcher at the Sapienza University of Rome.

In the past few years, three species of bone-skipper have been rediscovered in Europe, setting off a buzz among fly aficionados. But many bone-skippers were found by amateur scientists and recorded in photographs or video; actual specimens of the flies are few and far between. For the first time, Cerretti and colleagues have established a "type specimen" or "neotype" for one bone-skipper species, to which all of these bone-skippers will be compared in the future, in order to be identified.

The flies' "previous taxonomy was almost completely incorrect a mess," Cerretti told LiveScience. "If you have no good specimens, you have no good taxonomy."

The newly typed species, Centrophlebomyia anthropophaga, was first described by a scientist in 1830 "based solely on his memory of specimens he had observed in large numbers destroying preparations of human muscles, ligaments and bones in the Paris School of Medicine in August 1821," according to a study detailing Cerretti's findings published online in June in the journal ZooKeys.

Aptly named

The bone-skippers get their name from the prominence of bone in the heavily decayed carcasses they call home. Also, developing flies have a habit of jumping or "skipping" up and down, so these carcasses appear "alive with larvae," Cerretti said. (This makes them similar to the cheese fly, which is "famous in Italy," Cerretti said, adding that the cheese fly's maggots are known to jump out of infested cheeses. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

To jump, the bone-skippers connect their mouth hook to their tail and contract their dorsal muscles, letting go and flinging them upward. This dorsal muscle contraction is similar to the way click beetles propel themselves, Cerretti said.

Another species of bone-skipper, Thyreophora cynophila, was discovered in Mannheim, Germany, in 1798. At first, they were called dog flies, as they were found in a dead canine. They had been thought to be extinct for about 160 years before being found again in Spain in 2010. This species was noted for its alleged capacity to emit a luminous shine from its large, bright orange head.

Little known

Usually, bone-skippers prefer even larger dead animals, including humans. Researchers speculate that they may have been more abundant in preindustrial times, when larger mammals were more prevalent throughout Europe, and carcasses weren't disposed of as quickly as they are today.

Very little is known about bone-skippers' life history, other than that the larvae feed on carcasses and spend the summer developing in the soil below, Cerretti said, adding that the fly's keen sense of smell helps it find dead animals as it flies over snow.

In addition to being found in large carcasses, bone-skippers have turned up in a bag of dead, decaying snails; dead rodents; traps baited with dead squid; and a dead bird, according to the study.