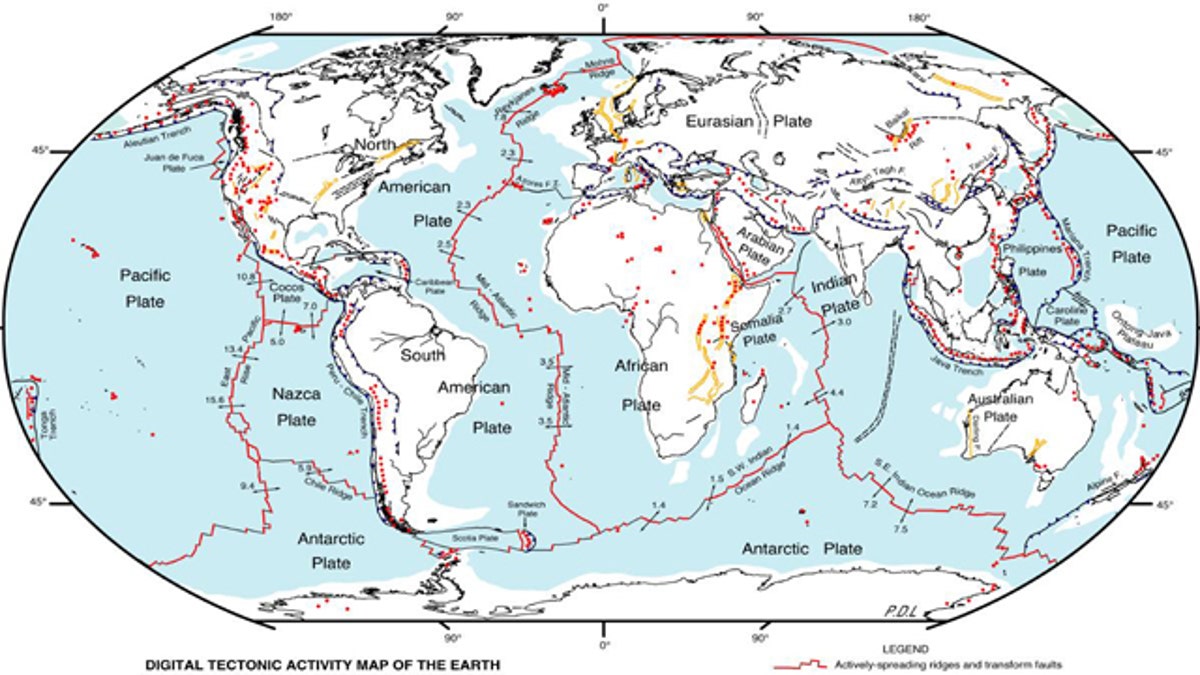

A map of world tectonic activity. Red lines are plate boundaries, arrows indicate spread rate and direction, red dots are active volcanic centers and yellow lines indicate faults or rifts. (NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center)

Strong aftershocks can be associated with major temblors, even weeks or years after the main event. But they are primarily felt in the first 24 to 48 hours, and more should be expected.

"A large, vigorous aftershock sequence can be expected from this earthquake," warns the U.S. Geological Survey. There have already been a number of aftershocks to hit Chile since the devastating 8.8 magnitude quake that struck early Saturday, the largest registering at magnitude 6.9, according to the USGS.

In the 2 1/2 hours following the 90-second quake, the U.S. Geological Survey reported 11 aftershocks, of which five measured 6.0 or above.

"Aftershocks are earthquakes," said Carrieann Bedwell, geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Earthquake Information Center (NEIC). "When there's a large earthquake some like to say aftershocks occur because of a readjusting of the fault itself; it continually readjusts because it did have such a large energy release," Bedwell said.

The shocks are primarily felt in the first 24 to 48 hours, but can come days, weeks, or even years later. Eight days after the earthquake that devastated the Haiti in January, a 6.1-magnitude quake hit the island nation -- a strong aftershock associated with the major temblor, even though it was more than a week later.

"The aftershock refers to an earthquake that is close to the epicenter or within the rupture zone of a large earthquake, in that case the Haiti region where the 7.0 earthquake happened," Bedwell said. Scientists define the rupture zone as the area in which energy was released from a major earthquake.

To tease out whether the shaking is considered an aftershock or a new quake, scientists also look at the depth where the new shaking started. In the case of the Haiti quake and aftershock, both were shallow, occurring just below the surface.

"That's another parameter we look at when we are determining whether this is an aftershock to a large earthquake or not," Bedwell said.

For the purposes of calculating other variables, the default is 10 kilometers, or 6.2 miles, below the surface. That's why this depth is reported for both the major earthquake and its aftershock.

"Depth is the hardest thing to actually determine on shallow earthquakes," said Don Blakeman, a geophysicist at the USGS and NEIC. "We have seismometer stations all over the world, but they are basically at the surface. We don't have any that are at depth. Most of the seismometers are no deeper than 200 or 300 feet."

He added, "It's a big deal to drill 10 kilometers," in order to insert a seismometer. "We can look at the recording of each of the waves at each station and even though we can't come up with an exact number we can see by the character of the waves that it's a shallow quake," Blakeman said.

A shallow quake also means energy gets released very close to the surface, which can cause violent ground-shaking.

Even though aftershocks are usually expected, they can still take scientists and survivors by surprise.

"Aftershocks are unpredictable," Bedwell told LiveScience. "We can predict that they are going to happen, but in terms of getting time and magnitude, that is unpredictable."

LiveScience.com contributed to this report.