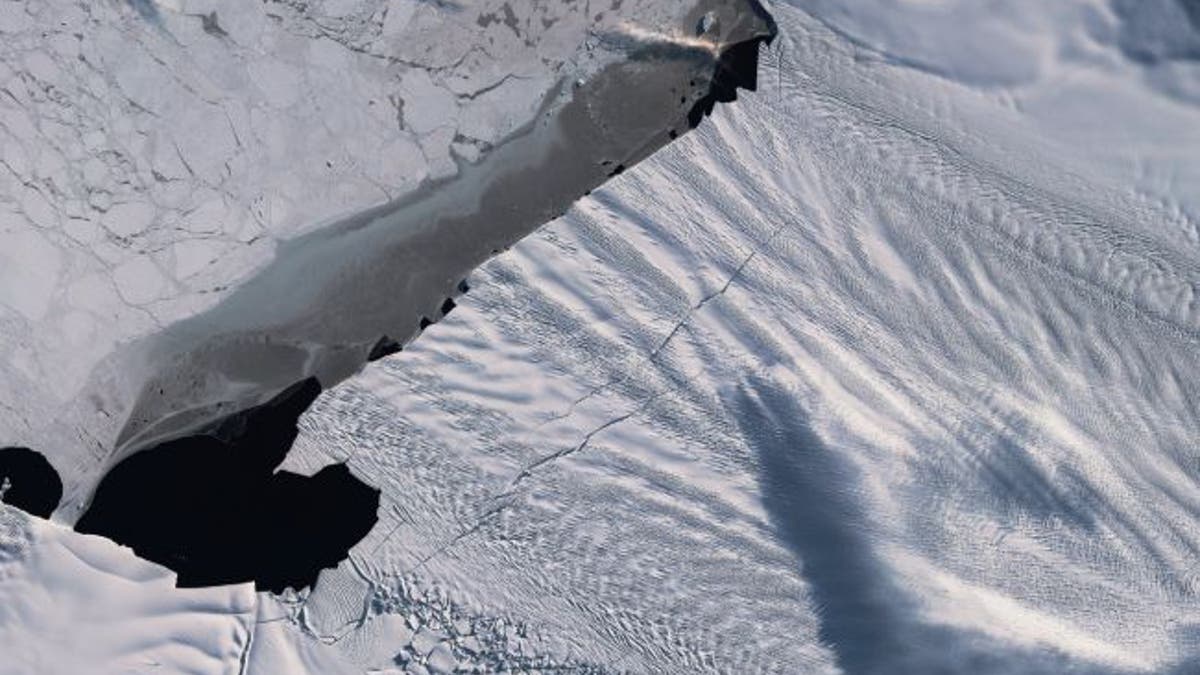

This image shows the two cracks captured by the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite on Sept. 14, 2019. (Credit: ESA, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

Two cracks are growing in western Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier, and they are an ominous warning that major ice loss is on the way.

This isn't the first major ice loss in recent years. Nearly a year ago, on Oct. 29, 2018, an iceberg measuring approximately 116 square miles (300 square kilometers) calved from the glacier, less than one month after a large crack appeared.

Soon after the calving of iceberg B46, a chunk that accounted for 87 square miles (226 square km) of the October 2018 ice loss, the two new cracks appeared, said Mark Drinkwater, head of the Earth and Mission Sciences Division at the European Space Agency (ESA).

These cracks were spotted in early 2019 by the ESA's Copernicus Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellites.

Recent satellite observations reveal that the new cracks are growing, the ESA reported in a statement. Each of the cracks now measures around 12 miles (20 km) in length. Their expansion suggests the ice sheet is facing imminent and significant ice loss, according to the ESA.

Related: Photo Gallery: Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier Cracks

"Sentinel-1 winter monitoring of their progressive extension signals that a new iceberg of similar proportions will soon be calved," Drinkwater said in the statement. To put that into perspective, an iceberg that large would span more than twice the area of Paris.

Both Sentinel satellite missions perform polar observations. But Sentinel-1's paired orbiters are particularly useful for monitoring the status of ice at Pine Island Glacier, as these satellites use an imaging system called synthetic aperture radar (SAR) that can capture photos year-round, during winter's dark months and in any type of weather, according to the ESA.

Like an icy tongue, Pine Island Glacier links the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to the Amundsen Sea. It is one of the fastest-retreating glaciers in Antarctica, and calving incidents have increased in recent years, NASA reported. Warming ocean currents are also melting the glacier from underneath, washing ice away faster than the glacier can replenish it, the ESA said.

Prior to the 2018 calving, the glacier suffered two more massive ice losses in 2015 and 2017, raising concerns among glaciologists for the region's future stability.

"In terms of frequency, it's happening more than before," Seongsu Jeong, a postdoctoral researcher at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at The Ohio State University, told Live Science in 2017.

- In Photos: The Vanishing Glaciers of Europe's Alps

- Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice

- Time-Lapse Images of Retreating Glaciers

Originally published on Live Science.