Earth's magnetic poles could flip sooner than originally expected. (UC Berkeley)

A pilot looking down at her plane controls and realizing magnetic north is hovering somewhere over Antarctica may sound like a scene from a science-fiction movie, but new research suggests the idea isn't so far-fetched in the relatively near future.

A magnetic field shift is old news. Around 800,000 years ago, magnetic north hovered over Antarctica and reindeer lived in magnetic south. The poles have flipped several times throughout Earth's history. Scientists have estimated that a flip cycle starts with the magnetic field weakening over the span of a few thousand years, then the poles flip and the field springs back up to full strength again. However, a new study shows that the last time the Earth's poles flipped, it only took 100 years for the reversal to happen.

The Earth's magnetic field is in a weakening stage right now. Data collected this summer by a European Space Agency (ESA) satellite suggests the field is weakening 10 times faster than scientists originally thought. They predicted a flip could come within the next couple thousand years. It turns out that might be a very liberal estimate, scientists now say. [Infographic: Explore Earth's Atmosphere Top to Bottom]

"We don't know whether the next reversal will occur as suddenly as this [previous] one did, but we also don't know that it won't," Paul Renne, director of the Geochronology Center at the University of California, Berkeley,said in a statement.

Geologists still are not sure what causes the planet's magnetic field to flip direction. Earth's iron core acts like a giant magnet and generates the magnetic field that envelops the planet. This helps protect against blasts of radiation that erupt from the sun and sometimes hurtle toward Earth. A weakening magnetic field could interrupt power grids and radio communication, and douse the planet in unusually high levels of radiation.

While the ESA satellite studied the magnetic field from above, Renne and a team of researchers studied it from below. The researchers dug through ancient lake sediments exposed at the base of the Apennine Mountains in Italy. Ash layers from long-ago volcanic eruptions are mixed into the sediment. The ash is made of magnetically sensitive minerals that hold traces of Earth's magnetic field lines, and the researchers were able to measure the direction the field was pointing.

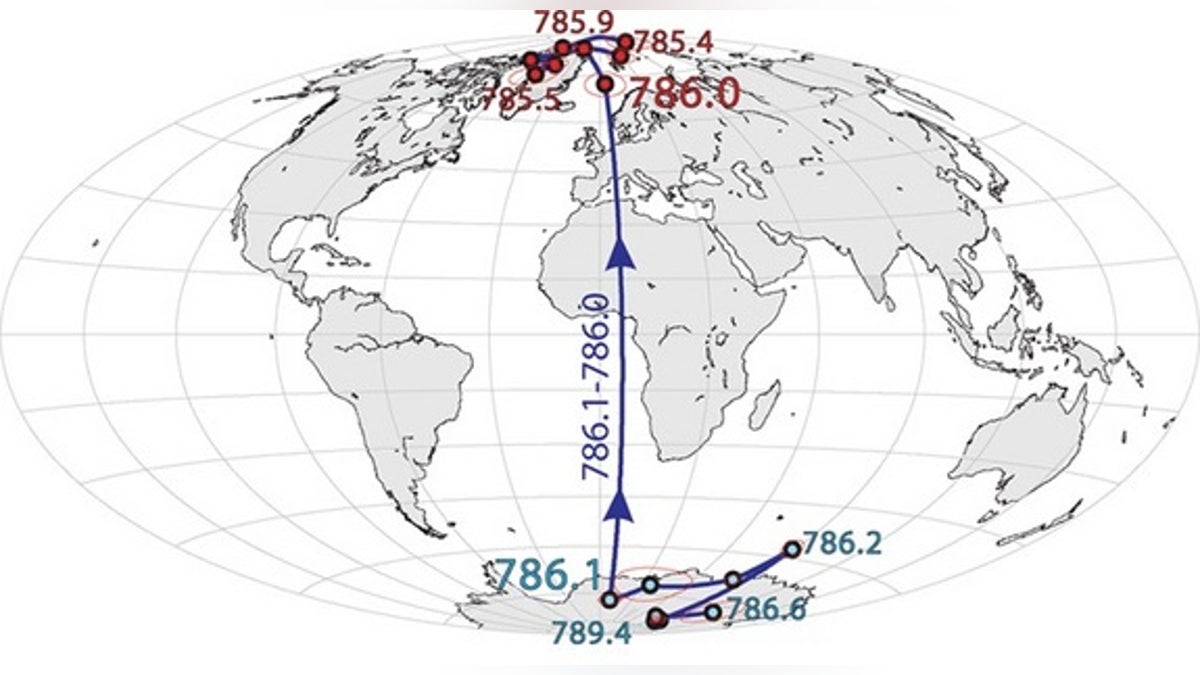

Renne and colleagues then used a technique called argon-argon dating which works because radioactive potassium-40 decays into argon-40 at a known rate to determine the age of the rock sediment. The layers built up over a 10,000-year period, and the researchers could pinpoint where the poles flipped in the rock layers. The last flip happened around 786,000 years ago.

Sudden swap

The sediment layers also showed the magnetic field was unstable for about 6,000 years before the abrupt flip-flop. The period of instability included two low points in the field's strength, each of which lasted about 2,000 years.

Geologists don't know where the magnetic field is now in that reversal timescale or if this flip will even follow the same pattern as the last. The bottom line is that no one is sure when it's coming.

"We don't really know whether the next reversal is going to resemble the last one, so it's impossible to say whether we're just seeing the first of possibly several excursions (slight movements), or a true reversal," Renne told Live Science in an email.

Magnetic doomsday?

While a pole flip could cause a few technical issues, there's no need to panic. Scientists have combed the geological timeline for any evidence of catastrophes that might be related to a magnetic flip. They haven't found any.

The only havoc that a reversal would wreak is interference in the global electric grid. No direct evidence remains of past catastrophes triggered by a magnetic flip.

However, if the magnetic field weakens enough or temporarily disappears during the flip, then the Earth could be hit with dangerous amounts of solar radiation and cosmic rays. The exposure could mean that more people develop cancer, Renne said, though there's no scientific proof this could happen.

Renne said more research is needed to understand the possible consequences of a shifting magnetic pole.

The new study will be published in the November issue of the Geophysical Journal International.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.