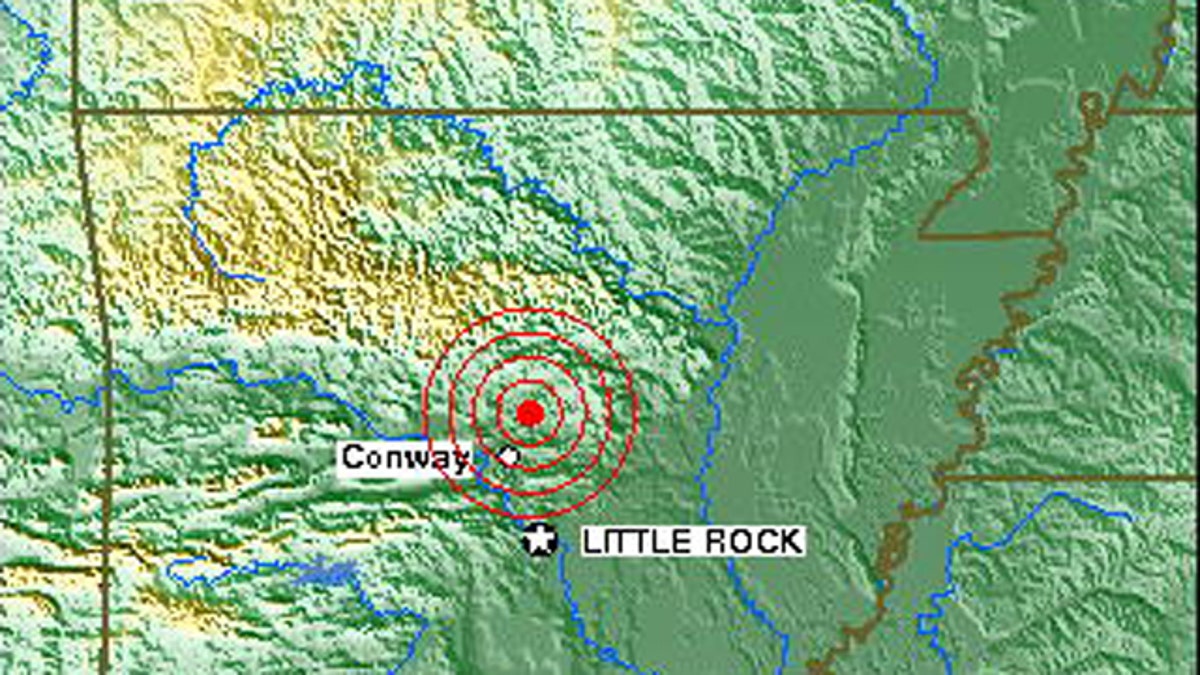

(USGS)

The sudden swarm of earthquakes in Arkansas -- including the largest quake to hit the state in 35 years -- is very possibly an after effect of natural-gas drilling, experts warn.

At issue is a practice called hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," in which water is injected into the ground at high pressure to fracture rock and release natural gas trapped within it.

Geologists don't believe the fracking itself is a problem. But Steve Horton, an earthquake specialist at the University of Memphis Center for Earthquake Research and Information (CERI), is worried by a correlation between the Arkansas earthquake swarm and a side effect of the drilling: the disposal of wastewater in injection wells.

"Ninety percent of these earthquakes that have happened since 2009 have been within 6 kilometers of these salt water disposal wells," he told FoxNews.com. The timing is too coincidental to ignore, Horton said.

Salt water is a common by-product of the fracking process, and the simplest solution is to inject the toxic wastewater back into the ground. But that can lubricate the surrounding rock, experts warn, possibly leading to quakes.

"They started doing these injection wells in the area that we're talking about in April of 2009. Since that time, there has been an increase in the rate of seismicity," Horton told FoxNews.com. "The increase in the rate of activity we've seen is temporally associated with the use of these wells to dispose of fluids in the subsurface."

Hanan Mahdi, a seismologist at the University of Arkansas, noted a similar connection in an interview with the International Business Times. She speculated that there could be two kinds of seismic activity in the area -- one natural, the other caused by pumping salt water into the ground.

"People say 'well, there were earthquakes here before the natural gas companies started, why should it be different now?'" Mahdi said. "Really, it could be both. We need to study this more and get a better picture of the geology here."

Scientists are slow to draw conclusions on any subject, and despite years of speculation, there is still little consensus about whether the practice is contributing to the quakes.

In 2009, the small town of Cleburne, Texas, experienced the first recorded earthquake in this Texas town's 140-year history, quickly followed by another four shortly afterwards. Was natural gas drilling -- which began in earnest in 2001 and brought great prosperity to Cleburne and other towns across North Texas -- causing the quakes?

"I think John Q. Public thinks there is a correlation with drilling," Mayor Ted Reynolds said. "We haven't had a quake in recorded history, and all the sudden you drill and there are earthquakes."

Horton also pointed to quakes in West Virginia, noting the same pattern of unusual seismic activity where previously there had been none.

"That isn't a place where you usually have earthquakes," he told FoxNews.com. When the West Virginia Oil and Gas Commission forced the disposal companies to cut back on their injection rate and pressure, the professor said, the earthquakes there seem to have dissipated.

While the debate continues, the Arkansas Oil & Gas Commission has imposed an emergency moratorium on the drilling of new injection wells in the area. Wells that were active before the moratorium, which was passed in December, can remain in operation, however.

According to a list published on the commission's website, there are currently 412 companies connected to the oil and gas industry in the state. But there are three companies digging for gas using seven active disposal wells in the moratorium area -- three commercial and four non-commercial, Shane Khoury, deputy director and general counsel for the commission, told FoxNews.com.

Southwestern Energy, which announced production in 2008 of more than 500 million cubic feet of natural gas per day from the state's Fayetteville Shale, and Chesapeake Energy, operate the non-commercial wells. Calls and e-mails to both companies were not immediately returned.

XTO, the third company, was recently purchased by Exxon, Khoury said. Clarita Operating and Deep-Six Water Disposal Services operate for-profit wastewater disposal wells in the area as well.

Some scientists remain unconvinced of the connection between the wells and the seismic activity, such as Berkeley Professor Chi-Yuen Wang whose research interests include the interaction of water and earthquakes.

"More detailed study is needed before one can clearly assess if salt water injection may be partly responsible for the earthquakes," he told FoxNews.com.

Some facts are clear, however: Seismic activity in Arkansas does seem to be increasing lately, lending support to the theory that drilling there is having a destabilizing effect.

Scott Ausbrooks, a seismologist with the Arkansas Geological Survey, said Sunday's record quake was at the "max end" of what scientists expect to happen, basing that judgment on this swarm and others in the past. It's possible that a quake ranging from magnitude 5.0 to 5.5 could occur, but anything greater than that is highly unlikely, he said.

The central Arkansas town of Greenbrier had been plagued for months by hundreds of small earthquakes, and after being woken up by the largest quake to hit the state in 35 years, residents said Monday they're unsettled by the increasing severity and lack of warning.

The U.S. Geological Survey recorded the 4.7-magnitude quake at 11 p.m. Sunday, centered just northeast of Greenbrier, about 40 miles north of Little Rock. It was the largest of more than 800 quakes to strike the area since September in what is now being called the Guy-Greenbrier earthquake swarm.

Nearly two dozen small quakes have been recorded in Arkansas in a single day.

The Associated Press contributed to this story.