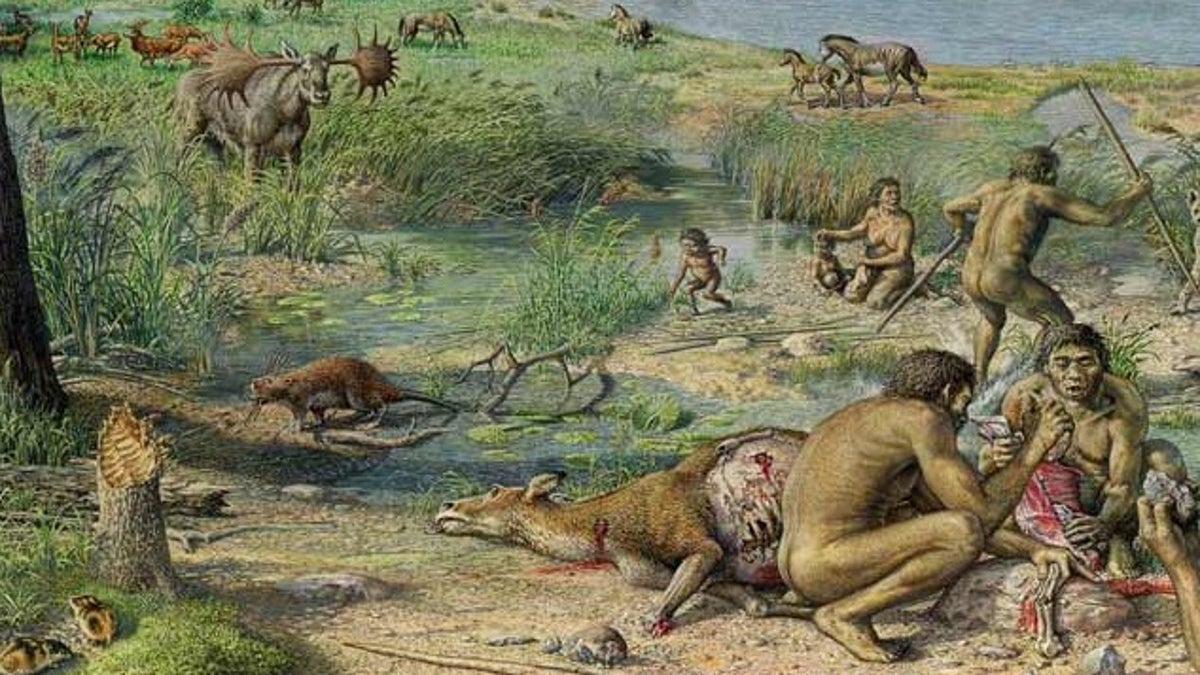

A reconstruction of prehistoric humans living around Happisburgh, UK, about 900,000 years ago. (John Sibbick/AHOB)

Ancient humans braved the cold in Britain over 800,000 years ago to create the first known settlement in northern Europe, according to researchers.

Their finding predates past evidence of prehistoric humans in Britain by at least 100,000 years. It also suggests that the early humans managed to survive in the cold northern climate, contrary to past thinking.

"We have found stone tools in several horizons, so they were there for at least several generations, if not longer," said Nick Ashton, an archaeologist and curator at the British Museum in London.

More than 70 flint tools and flakes turned up during an archaeological dig at the shore of Happisburgh in the northeastern part of England's Norfolk region.

Past evidence had indicated that early humans only moved north during warmer periods, when the northern climate more resembled that of the Mediterranean. But now archaeologists must consider how humans adapted to life near the northern forests, where edible plants and animals became scarcer and wintry conditions presented a greater challenge.

"My hunch is that they had more effective clothing and shelter than we'd previously imagined," Ashton told LiveScience. But he added that it only represents a guess.

Summer temperatures would have resembled those of Britain today, Ashton explained. But winter temperatures were probably several degrees lower.

Time and place

Still, the early humans in Britain had some advantages in their choice of location. Evidence from the Happisburgh site shows that the River Thames once flowed near there, so that freshwater pools and marshes would have appeared on the floodplain along with nearby salt marshes.

The flood plains would have also supported large animal prey such as mammoths, rhinoceros and horses, researchers said. That could have supplemented the scarcer prey of the nearby forested region.

"Having a range of resources is a safer environment to live in, whereby if one resource fails, you have others to rely on," Ashton pointed out.

Plant and animal remains from the archaeological site also helped narrow down the time period for archaeologists. For instance, some mammal remains discovered along with the flint tools suggest that the site dates back to at least 780,000 years ago, because those mammals went extinct around roughly that time.

Other remains recovered from the site belong to animals that are thought to have evolved only around 1 million years ago. That provides a rough timestamp between 1 million and 780,000 years ago for the site, Ashton said.

Paleomagnetism also helped timestamp the find. Researchers studied the orientation of iron minerals in the ancient river sediments and found that they had a reversed southerly magnetic orientation, as opposed to the northerly orientation that exists in Earth's magnetic field today.

The last major magnetic reversal period ended about 780,000 years ago – a fact that again helps narrow down the possible time period for the human presence.

Who lived there

Despite all the evidence surrounding the flint tools, archaeologists still have yet to recover fossilized remains of the toolmakers themselves.

"The best guess is Homo antecessor, which has been found at site of a similar age in northern Spain (Atapuerca)," Ashton noted. "However, as we have no human fossil evidence from Happisburgh, it is only a guess."

Homo antecessor, also known as Pioneer Man, was a hominin species that may have represented a common ancestor for both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

For now, the team led by scientists from the British Natural History Museum in London, the British Museum, University College London and Queen Mary, University of London, plans to push forward and try to find the elusive fossils.

"The next step is to explore other areas of the Norfolk and Suffolk coasts where similar sediments also survive," Ashton said.

More on this research is detailed in the July 7 issue of the journal Nature.