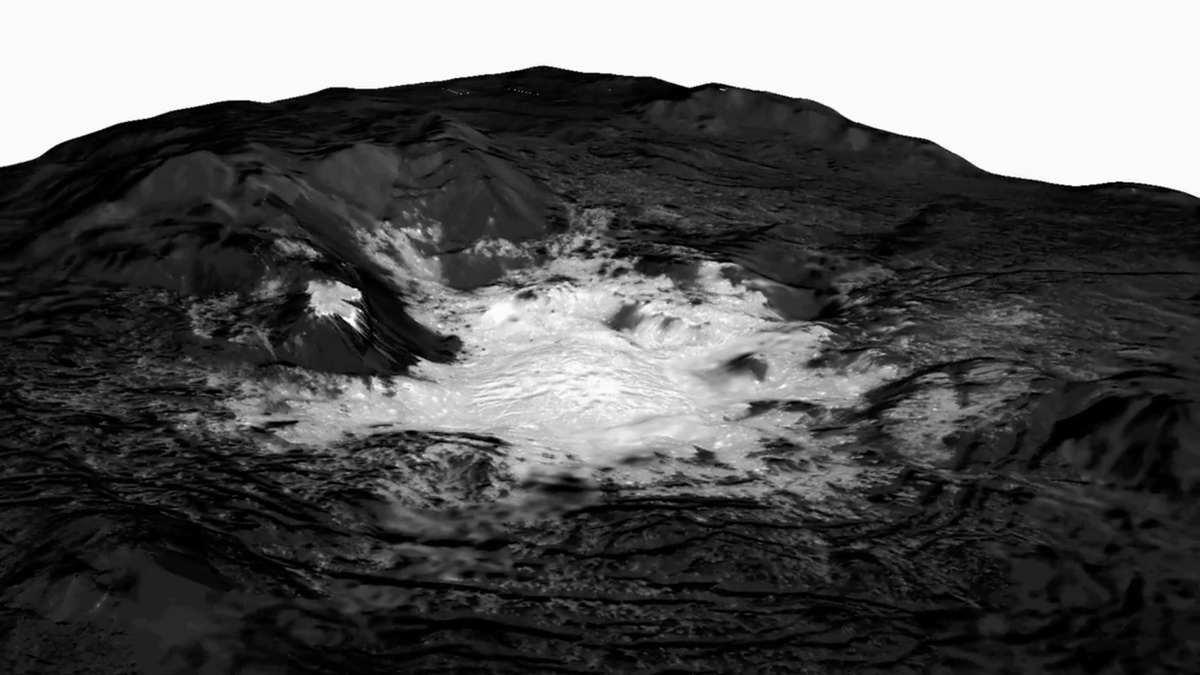

This mosaic of a bright spot on the dwarf planet Ceres known as Cerealia Facula combines images captured by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft from altitudes as low as 22 miles (35 kilometers) above Ceres' surface. The mosaic is overlain on a topography model based on images obtained during Dawn's low-altitude mapping orbit (240 miles, or 385 km altitude). No vertical exaggeration was applied. (NASA)

Darkness has finally come for Dawn.

NASA's Dawn spacecraft — which orbited the two largest objects in the asteroid belt, Vesta and Ceres, during its long and accomplished life — has run out of fuel and died, agency officials announced today (Nov. 1).

"Today, we celebrate the end of our Dawn mission — its incredible technical achievements, the vital science it gave us and the entire team who enabled the spacecraft to make these discoveries," Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C., said in a statement. [Photos: Asteroid Vesta and NASA's Dawn Spacecraft]

"The astounding images and data that Dawn collected from Vesta and Ceres are critical to understanding the history and evolution of our solar system," Zurbuchen added.

More From Space.com

Dawn's death is the second blow of a rapid one-two punch for space fans. NASA officials announced Tuesday (Oct. 30) that the agency's Kepler space telescope, which has discovered 70 percent of the 3,800 known alien planets to date, is out of fuel as well. Kepler will be decommissioned in the next week or two.

The $467 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007 to study the protoplanet Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres, which are about 330 miles (530 kilometers) and 590 miles (950 km) wide, respectively. Scientists regard these two bodies as leftovers from the solar system's planet-formation period, which explains the mission's name. ("Dawn" is not an acronym.)

Dawn arrived at Vesta in July 2011, then scrutinized the object from orbit for 14 months. The probe's work revealed many intriguing details about Vesta. For example, liquid water once flowed across the protoplanet's surface (likely after buried ice was melted by meteorite impacts), and Vesta sports a towering peak near its south pole that's nearly as tall as Mars' famous Olympus Mons volcano.

Dawn left Vesta in September 2012. The probe arrived at Ceres in March 2015, becoming the first spacecraft ever to orbit a dwarf planet, and the first to circle two bodies beyond the Earth-moon system. Such spaceflight feats were made possible by Dawn's superefficient ion engines, mission team members have said.

"The demands we put on Dawn were tremendous, but it met the challenge every time," mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in the same statement.

Dawn discovered a number of intriguing bright spots on Ceres. Mission team members determined these features to be salts, which were likely left behind when briny water from the subsurface bubbled up and boiled away into space.

The bright spots are young, suggesting that Ceres sported buried pockets of liquid water in the recent past — and probably even retains some of these pockets today, mission team members have said. The dwarf planet is therefore an intriguing target for astrobiologists, especially when another Dawn discovery is taken into account: The probe detected organic molecules, the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it, on Ceres' surface.

Dawn also spotted a 2.5-mile-high (4 km) "lonely mountain," by far the tallest surface feature on the dwarf planet. This mountain, which came to be called Ahuna Mons, is probably a cryovolcano that formed in the last few hundred million years, mission scientists have said.

"In many ways, Dawn's legacy is just beginning," mission principal investigator Carol Raymond, also of JPL, said in the same statement. "Dawn's data sets will be deeply mined by scientists working on how planets grow and differentiate, and when and where life could have formed in our solar system. Ceres and Vesta are important to the study of distant planetary systems, too, as they provide a glimpse of the conditions that may exist around young stars."

The mission team concluded that Dawn had run out of hydrazine after the probe missed scheduled communication check-ins yesterday (Oct. 31) and today. Hydrazine is the fuel used by Dawn's pointing thrusters, so the spacecraft can no longer orient itself to study Ceres, relay data to Earth or recharge its solar panels.

Dawn will remain in orbit around Ceres for at least 20 years, and probably much longer than that. Mission team members have said there's a greater than 99 percent probability that the probe won't spiral down onto Ceres' frigid, battered surface for at least five more decades.

The deaths of both Dawn and Kepler did not come as a surprise. Mission team members have known for months that the tanks of both spacecraft were getting very dry.

Originally published on Space.com.