Fox News Flash top headlines for June 30

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

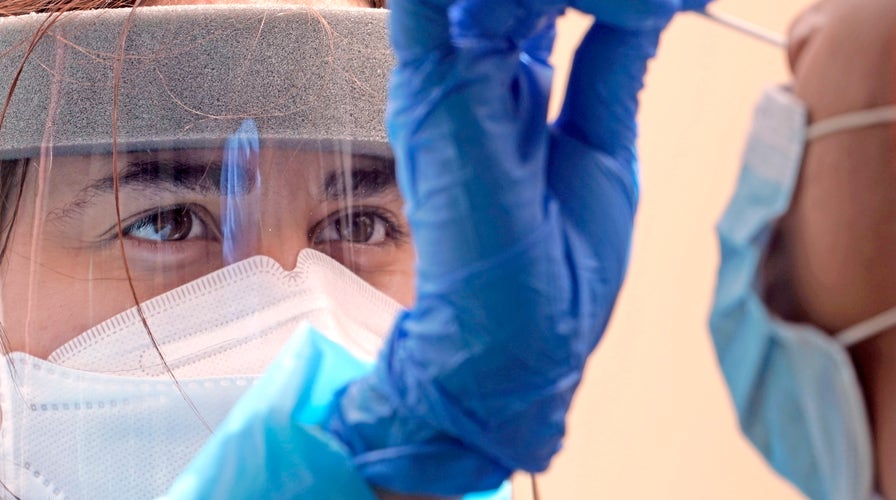

COVID-19 triggered changes in blood platelets could be a contributing factor to the onset of heart attacks and strokes in some patients with the disease, new research reveals.

Scientists from the University of Utah Health found that inflammatory proteins produced during infection significantly alter the function of platelets, making them "hyperactive" and more prone to form dangerous and potentially deadly blood clots.

Researchers hope that if they can better understand the causes of these changes, they could lead to more effective treatments for patients. Their report appears in Blood, an American Society of Hematology journal.

"Our finding adds an important piece to the jigsaw puzzle that we call COVID-19," said Robert A. Campbell, senior author of the study and an assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, in a statement. "We found that inflammation and systemic changes, due to the infection, are influencing how platelets function, leading them to aggregate faster, which could explain why we are seeing increased numbers of blood clots in COVID patients."

According to scientists, some evidence suggests that COVID-19 is associated with an increased risk of blood clotting, which can lead to other cardiovascular problems in some patients.

Researchers studied 41 COVID-19 patients hospitalized at University of Utah Hospital in Salt Lake City; next, they compared blood from these patients with samples taken from healthy individuals who were matched for age and sex.

COVID-19'S IMPACT DOCUMENTED BY SATELLITE IMAGERY IN NEW INITIATIVE FROM US, JAPAN AND EUROPE

The researchers found that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, seems to trigger genetic changes in platelets. Those changes also impact how platelets interacted with the immune system, likely contributing to respiratory inflammation that could result in more severe lung injury.

"There are genetic processes that we can target that would prevent platelets from being changed," Campbell explained. "If we can figure out how COVID-19 is interacting with megakaryocytes or platelets, then we might be able to block that interaction and reduce someone's risk of developing a blood clot."