Study: Civil War POWs' trauma shortened their sons' lifespans

According to a startling UCLA research study, Civil War-era data suggest that trauma experienced by POWs shortened the lifespan of their male children.

Civil War-era data suggest that trauma experienced by POWs shortened the lifespan of their male children, according to a startling UCLA research study.

UCLA Economics Professor Dora Costa analyzed records in the National Archives to track the lifespans of children of Union soldiers captured by the Confederacy. The study examined data on male and females born after 1866 who lived to at least 45 years of age.

The records were compared to data on the children of Union soldiers who survived the war but were never prisoners of war.

CIVIL WAR BATTLEFIELD DISCOVERY: SURGEON'S BURIAL PIT REVEALS SOLDIERS' REMAINS, AMPUTATED LIMBS

A key factor in the research was when the POWs were held by the Confederacy. During the early stages of the conflict, prisoner exchanges occurred frequently, although this was less common from 1864 to 1865 when the terms of exchange became contentious. During that time, camps were often overcrowded and conditions such as scurvy and malnutrition were much more common than at the start of the war.

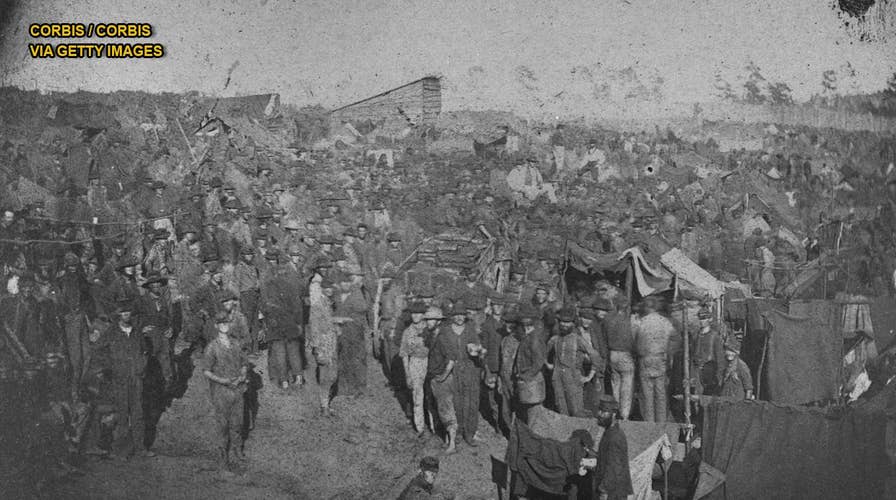

File photo - Originally known as Camp Sumter, Andersonville was a Confederate prison camp that became notorious for maltreatment of prisoners. (Photo by © CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

At Andersonville prison in Georgia, for example, 13,000 of the 45,000 Union soldiers imprisoned there died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure over a 14-month period. Andersonville is now a national historic site.

Researchers studied the records of 2,342 children of 732 POWs during the period when no prisoner exchanges took place, as well as 2,416 children of 715 POWs from when exchanges were common. Data on 15,145 children of 4,920 veterans who had not been POWs were also studied.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN LETTER MYSTERY 'ALMOST CERTAINLY' SOLVED, EXPERTS SAY

Costa discovered that sons of POWs in the worst camp environments were 1.11 times more likely to die at any given age after 45 years of age that the sons of non-POWs and 1.09 times more likely to die at any given age than the sons of POWs who had been imprisoned in camps when conditions were better.

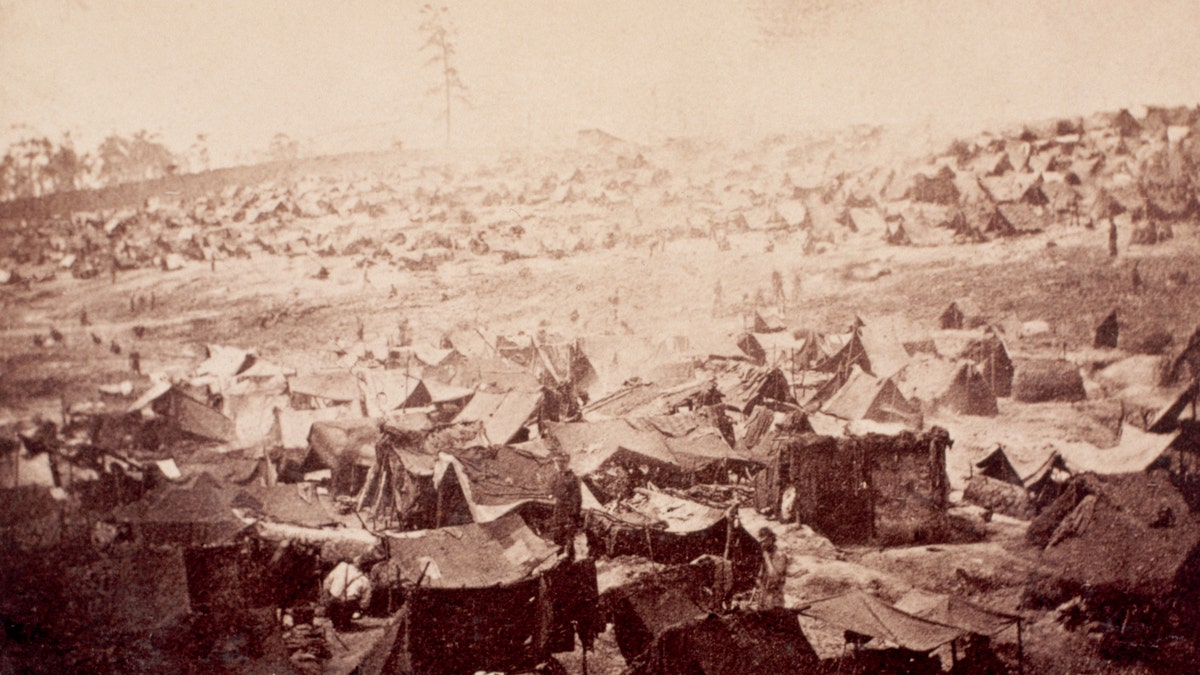

File photo - Confederate prisoners under guard during the Civil War (National Archives)

The professor told Fox News that she started the study expecting to write a paper about socioeconomics. Instead, the results offer fresh insight into epigenetics, which is the study of inherited “biological triggers” that can affect genes and how the body’s cells react to genetic data, with altering underlying DNA sequence.

One example of epigenetics would be genes for type 2 diabetes being switched “off or on” by environmental stimuli, Costa told Fox News.

CIVIL WAR-ERA SHIPWRECK FOUND OFF NORTH CAROLINA COAST

Common causes of death among veterans’ sons were cancer and cerebral hemorrhage, in keeping with epigenetic studies of starvation in male mice, according to the research study. Fathers’ POW status had no impact on their daughters’ health, it added.

The fact that sons’ lifespans were impacted and daughters were not, indicates an “epigenetic effect transmitted along the Y chromosome,” Costa said. The Y chromosome is only found in males.

While the study’s findings are alarming, researchers note that the impact of trauma was likely mitigated by nutrients taken by mothers during pregnancy. Sons who were born during the later months of 1866 to soldiers who were POWs when conditions in the Confederate camps declined fared better than those born earlier in 1866. Costa said that this is likely the result of their mothers having better access to nutrition during their pregnancies.

DOES THIS PHOTO OF ULYSSES S. GRANT LOOK STRANGE TO YOU?

For sons born in the fourth quarter of 1866 to mothers with adequate nutrition during their pregnancies, there was no difference in the eventual death rates of POW and non-POWs’ sons. However, for sons born during the second quarter of 1866, when maternal nutrition was inadequate, the sons of ex-POWs who experienced the harshest conditions were 1.2 times more likely to die than sons of non-POWs and sons of ex-POWs who had been held in less severe conditions.

“Because ex-POW stress was so extreme and because there were such big seasonal differences in maternal nutrition, it is easier to detect effects in the past,” Costa told Fox News. “The lesson for today is that effects are possible and they can be reversed.”

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, was published in the journal Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences.

Follow James Rogers on Twitter @jamesjrogers