Vaquita. Photo: NOAA Fisheries.

A rare species of fish and the world’s smallest porpoise – both face extinction as poachers work the waters of Mexico’s Gulf of California to meet the growing demand in Asian markets for the fish’s swim bladder.

The totoaba – the world’s largest type of drum fish – was once a ubiquitous presence in the Gulf of California, but illegal fishing fueled by demand in China for its swim bladder has decimated the fish’s population and led the Mexican government to outlaw fishing for the totoaba and to heavily monitor its home waters.

Adding to the situation is the widespread use of gillnets, which unintentionally trap other species such as the vaquita – a tiny porpoise whose worldwide population is estimated to be less than 60 – which poachers fish for totoaba.

“Enforcing the ban is always difficult because when you have something that is in high demand and can fetch high prices, the incentive is still there for illegal fisherman,” Leigh Henry, a senior policy advisor at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) told FoxNews.com. The fish’s swim bladders, which help them maintain buoyancy, can fetch over $60,000 per kilogram — more than a kilo of cocaine – and are used in traditional Chinese medicine as a treatment a treatment for fertility, circulatory and skin problems.

UNDERWATER LISTENING STATION DETECTS THE CALLS OF RARE WHALES

This March 2013 image provided by the U.S. attorney's Office shows Totoaba bladders displayed at a U.S. border crossing in downtown Calexico, Mexico. (The Associated Press)

While the decline in the totoaba population occurred only after the bahaba – a fish with a similar swim bladder - was overfished, the vaquita faced threats since its discovery in the 1950s. Legal gillnet fishing for shrimp in the Gulf of California threatened the species until the 1980s when conservation groups helped introduce alternative fishing techniques like trawling and the population began to level off.

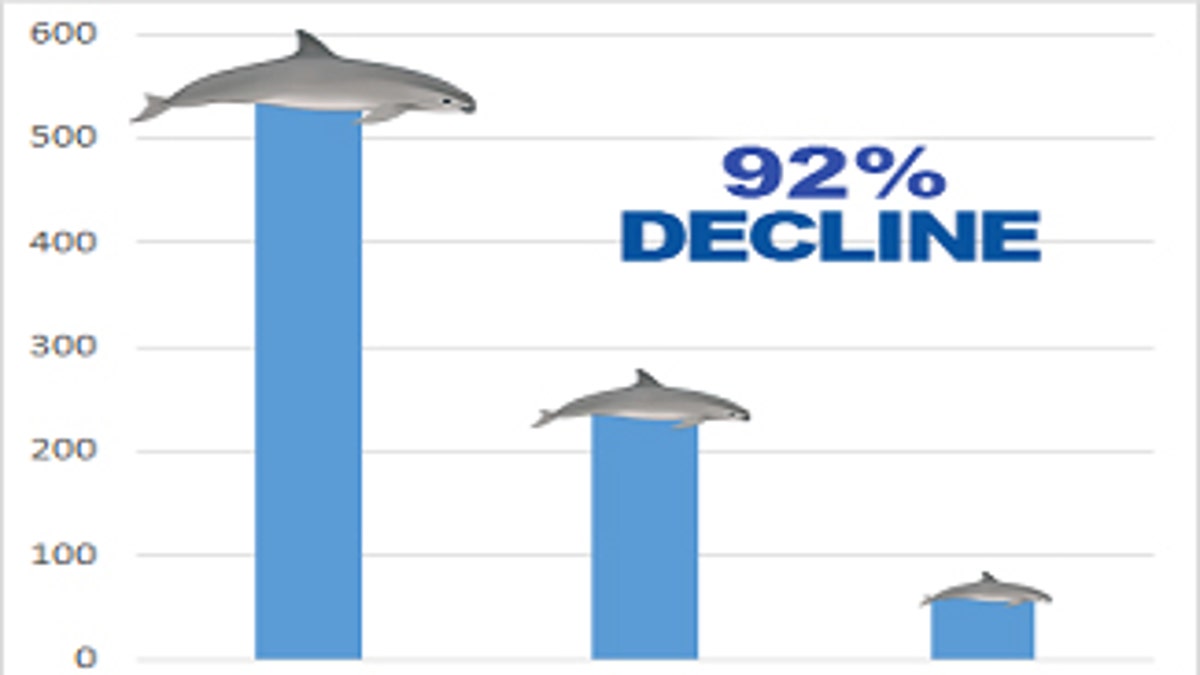

In the last five years, however, the poaching of totoaba has once again put the vaquita in danger of extinction. Earlier this year, the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society found three dead vaquitas in the same number of weeks and researchers who use acoustic devices to detect the porpoise’s sonar-like squeaks or clicks have reported hearing less and less noise as the population dwindles.

"We are watching this precious native species disappear before our eyes," Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, chair of the International Commission for the Recovery of the Vaquita, told the Associated Press back in March.

Conservationists at the WWF, Sea Shepherd and other groups say they are doing the best they can to protect the two endangered species, but the type of fisherman hunting totoaba are vastly different from the shrimpers of a few decades ago.

(CIRVA VII report/NOAA)

WANT TO MONITOR BEARS? TRY CHECKING THEIR SALIVA

“The threat is still the gillnet, but you’re now dealing with a whole new industry,” Henry said. “Instead of legal shrimp fishers, we’re now dealing with transnational organized crime and people working on the black market.

In the last few years, the Mexican government has stepped up its efforts to curtail poaching in the Gulf of California – the body of water that separates the Baja Peninsula from the rest of Mexico – adding in June two small boats, a number of vehicles and 135 sailors to an enforcement force deployed in 2015 under the Upper Gulf of California Integrated Protection Program. The new support joined the 13 ships, five vehicles, a helicopter-carrying ship and a plane already deployed to combat illegal fishing in the region.

The U.S., which is seen as the main transshipment country for the totoaba’s bladders, has also joined in the fight against traffickers. Last year, U.S. Customs and Border Protection seized 1,328 pounds of totoaba fish bladders that were in route to Hong Kong.

While conservationists agree that the main battle to save the totoaba and vaquita is in Mexican water, they acknowledge that the demand for the bladders in China is the reason for the illegal trade and argued that officials in Beijing and Hong Kong need to crack down on the underground fish trade.

'WORLD'S SADDEST POLAR BEAR' MOVED AFTER OUTPOURING OF OUTRAGE TOWARDS CHINESE MALL

The problem, experts argue, is that wildlife trafficking is so pervasive in the world’s most populous nation that authorities are stretched thin and forced to give priority to larger cases.

“A lot of the response we get from the Chinese is that trafficking of totoaba bladders is not as significant as other species,” Henry said. “But while it may not be as prevalent as other animals, it is still significant because it could lead to the extinction of at least one species.”