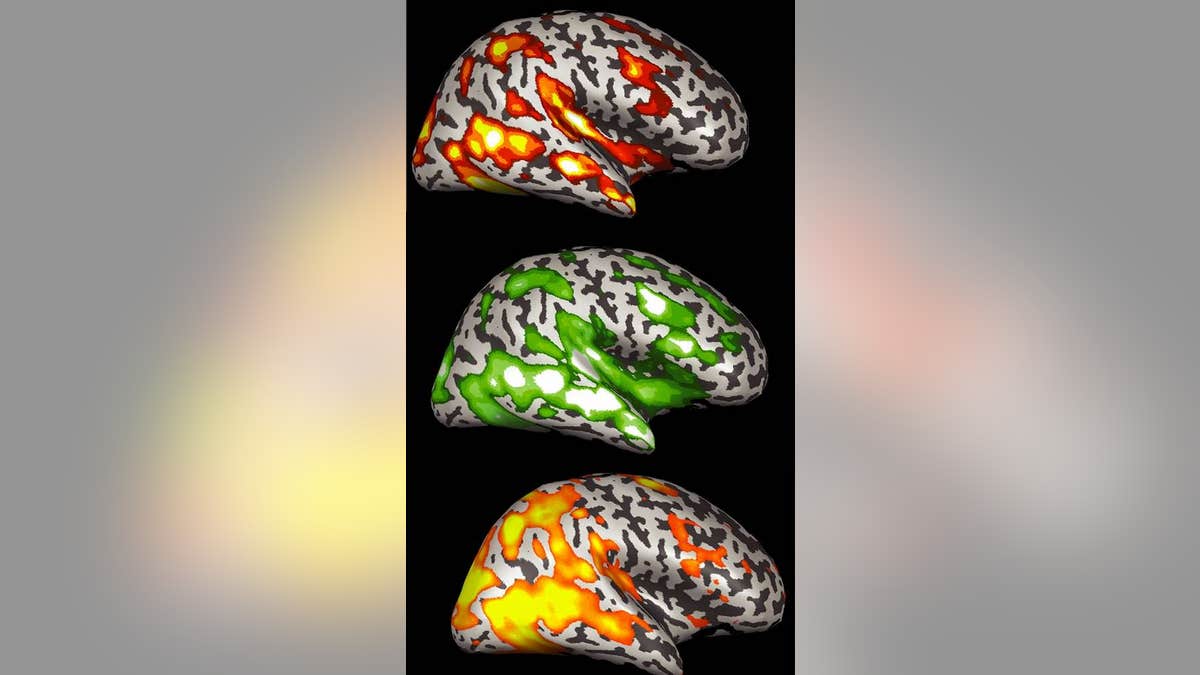

Researchers created "neural maps" of the thought processes for children and adults watching Sesame Street, and compared the groups. (Top: brain activity correlations between children and adults; Middle: between children and other children; Bott (Jessica Cantlon, University of Rochester)

Children are not the only ones who can learn from Big Bird — brain scans of children and adults watching "Sesame Street" reveal how brains change as they learn reading and math, researchers say.

One goal of brain imaging is discovering more about how children learn. Such an understanding of the building blocks of learning might help diagnose and treat learning difficulties.

For instance, "when children fail to learn mathematics well, there could be a number of different reasons for that — it could be that they have weak concepts of numbers, that they have poor memory, that they have limited attention," researcher Jessica Cantlon, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Rochester in New York, told LiveScience. Brain tests could help determine the precise cause of a kid's math impairments, "because different patterns of brain activity likely accompany each of those different cognitive impairments."

Although scientists currently cannot see what goes on in the brains of children when they are learning in the classroom, Cantlon and her colleagues instead focused on analyzing what happens when kids watched educational television programs.

For the investigation, 27 children between the ages of 4 and 11 joined 20 adults in watching the same 20-minute "Sesame Street" recording as they had their brains scanned with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The video featured a variety of short clips with Big Bird, the Count, Elmo and other stars of the show, and focused on numbers, words, shapes and other subjects. The children then took standardized IQ tests for math and verbal ability. [See Elmo Video]

"This took three years," Cantlon said. "Working with children can be challenging ... It also took time for us to get the analyses right."

Using statistical algorithms, the researchers created "neural maps" of the thought processes for the children and the adults and compared the groups. Children whose neural maps more closely resembled those of adults scored better on standardized math and verbal tests, showing that the brain's neural structure, like other parts of the body, apparently develops along predictable pathways as people mature. [Inside the Brain: A Photo Journey Through Time]

This research also confirmed where these developing abilities are located in the brain. For math, adultlike neural patterns in the intraparietal sulcus, a region of the brain involved with the processing of numbers, were linked to higher scores. For verbal tasks, more mature patterns in Broca's area, which is linked to speech and language, predicted better verbal test scores in children.

Normal activities such as TV watching may be a better way of learning about "neural maturity" than the short and simple tasks typical of fMRI studies. For instance, when the children matched simple pictures of faces, numbers, words or shapes, the neural responses of the children did not predict their test scores like watching "Sesame Street" did, the researchers said.

The researchers stress "that these results do not mean that there is anything special about 'Sesame Street' in particular," Cantlon said. "We chose 'Sesame Street' because it is mainstream. There are likely lots of stimuli that could yield the same result."

Still, while this research does not advocate watching television, it does show that "neural patterns during an everyday activity like watching television are related to a person's intellectual maturity," Cantlon said. "It's not the case that if you put a child in front of an educational TV program that nothing is happening — that the brain just sort of zones out. Instead, what we see is that the patterns of neural activity that children are showing are meaningful and related to their intellectual abilities."

Future studies can help pinpoint what areas might be linked with difficulties with learning math or verbal tasks. Research could also see if educational television shows are better than noneducational shows at eliciting math- and verbal-related brain activity, Cantlon said.

Cantlon and her colleague Rosa Li detailed their findings online Jan. 3 in the journal PLOS Biology.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.