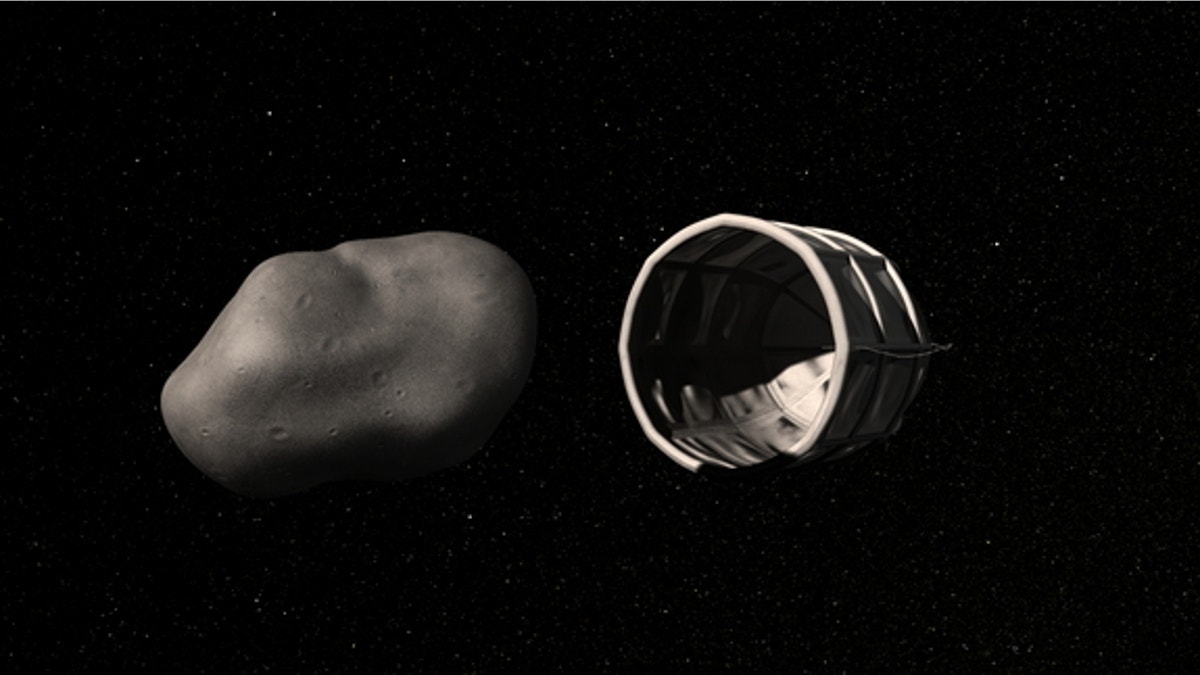

Small, water-rich near-Earth asteroids can be captured by spacecraft, allowing their resources to be extracted, officials with the new company Planetary Resources say. (Planetary Resources, Inc.)

A newly unveiled firm's asteroid-mining plans may be ambitious, but they're not any crazier than some extractive operations already under way here on Earth, company officials say.

The billionaire-backed Planetary Resources, Inc. announced Tuesday (April 24) that it hopes to mine near-Earth asteroids for water and precious metals, with the dual aims of making a tidy profit and helping open the final frontier to further exploration and exploitation.

Asteroid mining promises to be a multidecade effort requiring many billions of dollars of investment. But in that respect — and in the technological challenges that must be overcome — it's similar to deep-sea oil drilling, said Planetary Resources co-founder and co-chairman Peter Diamandis.

"They've literally created robotic cities on the bottom of the ocean, 5, 10 thousand feet below the ocean's surface — fully robotic cities that then mine 5 to 10 thousand feet down below the ocean floor to gain access to oil," Diamandis said Tuesday. "For me, that kind of work makes going to the asteroids to extract resources look easy." [Images: Planetary Resources' Asteroid Mining Plans]

Mining the heavens

While Planetary Resources has big dreams, it appears to have deep pockets as well. The company counts at least four billionaires among its investors, including Google execs Larry Page and Eric Schmidt, who are worth about $16.7 billion and $6.2 billion, respectively.

Filmmaker/explorer James Cameron is a Planetary Resources adviser, as are former NASA astronaut Tom Jones and MIT planetary scientist Sara Seager.

The company aims to extract platinum-group metals and water from nearby space rocks. The metals could drive down the prices of many consumer goods here on Earth, officials say, while the water has the potential to revolutionize space transportation.

Water can be broken into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen, the chief components of rocket fuel. Planetary Resources hopes its mining activities lead to the establishment of in-space "gas stations" that would allow a variety of spacecraft to refuel cheaply and efficiently. (Launching such propellant from Earth would be far more expensive, company officials say.)

Planetary Resources hopes to identify a suite of promising asteroid targets within the decade. Actual mining activities — which will be carried out by swarms of low-cost robotic probes in deep space — will come later.

Drilling in nearly 2 miles of water

The company is under no illusions about the challenges ahead.

"We're talking about something which is extraordinarily difficult," Diamandis said. Still, he stressed that it can be done, comparing asteroid mining's scale, scope and degree of difficulty with deep-sea oil drilling.

"These are commitments of 5 to 50 billion dollars in each of these platforms," Diamandis said. "It's extraordinary what humanity can now do."

To get an idea of what he's talking about, consider Shell Oil's Perdido platform in the Gulf of Mexico, which began oil production in March 2010. It floats in water 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) deep and taps a field that begins nearly 2 miles beneath the ocean's surface. [SOS! Major Oil Disasters at Sea]

Perdido sits about 200 miles (320 kilometers) off the Texas coast, too far from land to lay new pipeline cost-effectively, according to Shell officials. So the company decided to hitch Perdido into an existing pipeline 80 miles (128 km) away, using robotic submarines to make the intricate connections 4,600 feet (1,400 m) below the Gulf's surface.

The design and training stages for this submarine mission took a total of 2 1/2 years, Shell officials have said.

The Perdido platform cost about $3 billion to build, and Shell expects it to be in operation for more than 20 years, Reuters reported earlier this year. Over that period, the platform could generate $39 billion in revenue and $16 billion in profits, according to the Associated Press.

And rigs such as Perdido don't just suck oil up off the ocean floor. They're capable of accessing deposits at least 30,000 feet (9,144 m) below the seabed, after first dropping gear through nearly 2 miles of water.

Copyright 2012 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.