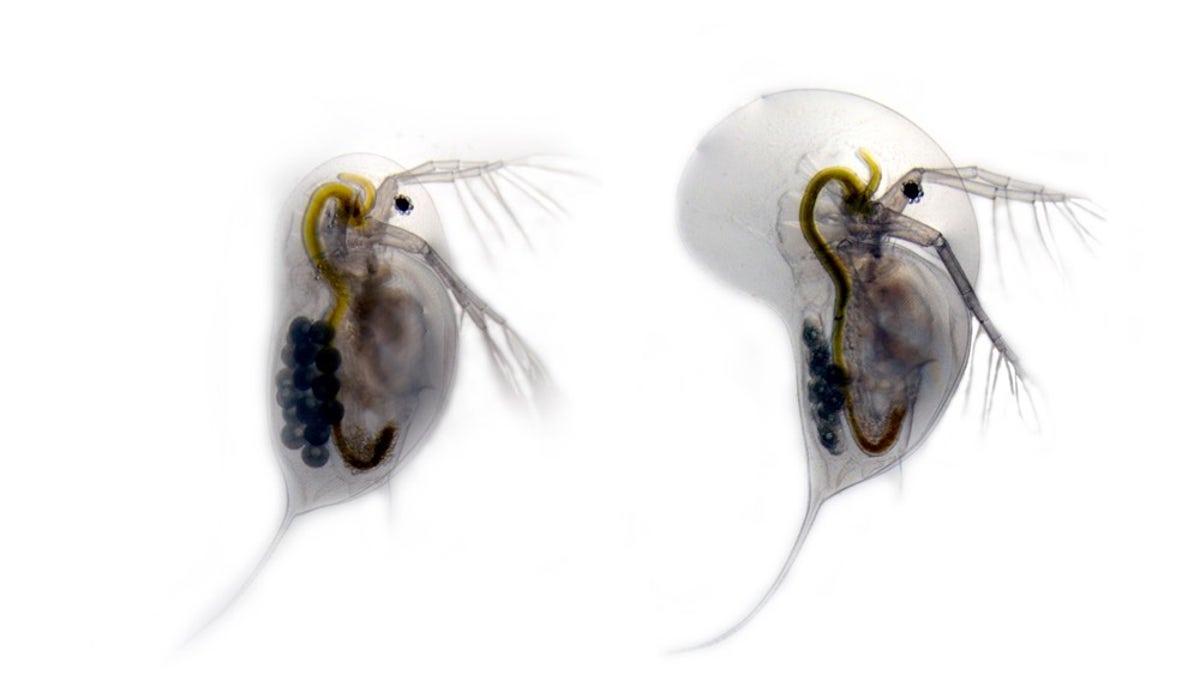

The water flea Daphnia longicephala in two different forms. On the left is the unarmored version of the species. On the right is the same animal with a large head crest and long tail spines. D. longicephala develops this (Dr. Linda Weiss)

Water fleas prepare for battle by growing armor that's customized to specific enemies, new research finds.

Tiny Daphnia species develop impressive protective structures as they mature, including pointy tail spines and tough helmets. Now, researcher Linda Weiss of Ruhr-University Bochum in Germany and her colleagues have found the neurotransmitters that help water fleas customize their bodies in response to the chemical cues in their watery environments.

"Dopamine, in particular, appears to code neuronal signals into endocrine [hormone] signals," Weiss said in a statement.

Daphnia is a genus comprising many species of the tiny crustaceans known as water fleas. Most are less than 0.2 inches (5 millimeters) long, and look much like translucent versions of the land-based fleas that give them their nickname.

When juvenile Daphnia molt and develop a mature exoskeleton, they mold their bodies based on the chemicals they encounter in the water. The water fleas use appendages called antennules to detect scents and chemicals left by predators (fish, for example, or the upside-down swimming insects called backswimmers). They then develop armor defenses in response to the threats they expect to face.

Related:

"These defenses are speculated to act like an anti-lock key system, which means that they somehow interfere with the predator's feeding apparatus," Weiss said. "Many freshwater fish can only eat small prey. So, for example, Daphnia lumholtzi grows head and tail spines to make eating them more difficult."

Weiss and her colleagues have found the intermediary steps that make this transformation occur. The antennules create brain signals when they detect chemical cues, which in turn cause the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Dopamine, in turn, cues the release of juvenile hormones that promote growth in particular body regions.

The same juvenile hormones promote growth in many other arthropods, Weiss said, which suggests that this developmental pathway is a widely shared way for crustaceans and insects to respond to environmental conditions.

Little Daphnia can also act as a canary in a coal mine for water quality, Weiss said. Understanding how water fleas change in response to chemical cues "will help in our understanding of the composition and population dynamics of freshwater ecosystems," Weiss said. "As freshwater is one of the most important resources on Earth, it is important to study the communities it holds."

Weiss was scheduled to present her findings, which have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, Wednesday at the annual meeting for the Society for Experimental Biology in Brighton, England.

Original article on Live Science.