Fox News Flash top headlines for Nov. 6

Fox News Flash top headlines for Nov. 6 are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com

The remains of an 11 million-year-old ape suggest that our ancestors started to stand upright millions of years earlier, according to scientists.

A team of researchers claims the fossilized partial skeleton of a male ape that lived in the humid forests of what is now southern Germany bears a striking resemblance to modern human bones.

In a paper published on Wednesday by the journal Nature, they concluded that the new species — dubbed Danuvius guggenmosi — could walk on two legs but also climb like an ape.

The findings “raise fundamental questions about our previous understanding of the evolution of the great apes and humans,” Madelaine Boehme of the University of Tuebingen, Germany, who led the research, told The Associated Press.

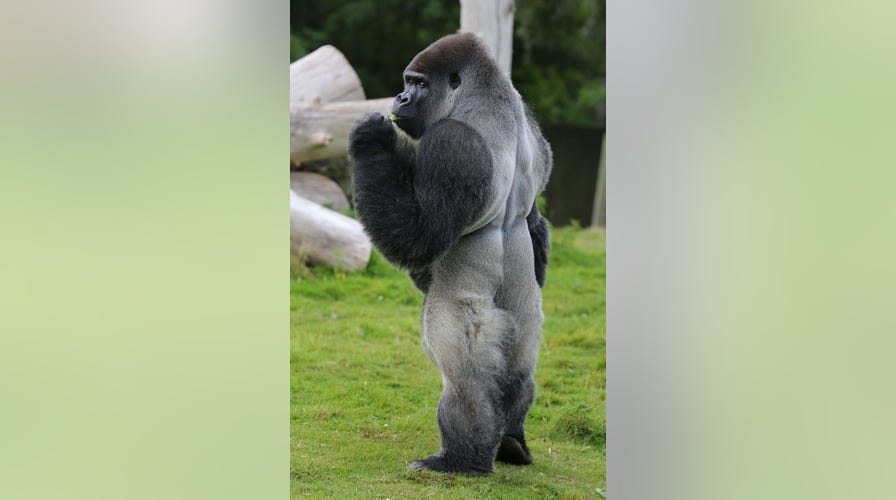

Ambam, a Western Lowland Gorilla, stands in his enclosure at Port Lympne Wild Animal Park near Ashford, Kent. He became an online sensation when footage of him aping humans with his unusual habit of walking upright was captured. (Getty Images)

Scientists have long been trying to discern when apes first evolved the ability to stand on two feet. Previous fossil records of apes that stood upright reportedly date to 6 million years ago.

Boehme, along with researchers from Bulgaria, Germany, Canada and the United States, examined more than 15,000 bones recovered from a trove of archaeological remains known as the Hammerschmiede, or Hammer Smithy, about 44 miles west of the Germany city of Munich.

Among the remains they were able to piece together were primate fossils belonging to four individuals that lived 11.62 million years ago. According to The Associated Press, the most complete, an adult male, likely stood about 3 feet, 4 inches tall, weighed 68 pounds and looked similar to modern-day bonobos, a species of chimpanzee.

“It was astonishing for us to realize how similar certain bones are to humans, as opposed to great apes,” Boehme told the wire service.

A man holds bones of the previously unknown primate species Danuvius guggenmosi in his hand in Tuebingen, Oct.17, 2019. Palaeontologists have discovered fossils in southern Germany that shed new light on the development of the upright corridor. (AP Photo/Christoph Jaeckle)

Scientists were able to reconstruct how Danuvius moved, concluding that it could straighten his legs to walk upright, as well as hang from tree branches.

“This changes our view of early human evolution, which is that it all happened in Africa,” Boehme explained.

Fred Spoor, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, told AP the fossil finds were exciting but would likely be the subject of much debate, not least because it could challenge many existing ideas about evolution.

“This is fantastic material,” said Spoor, who wasn’t involved in the study. “There undoubtedly will be a lot for people to analyze.”