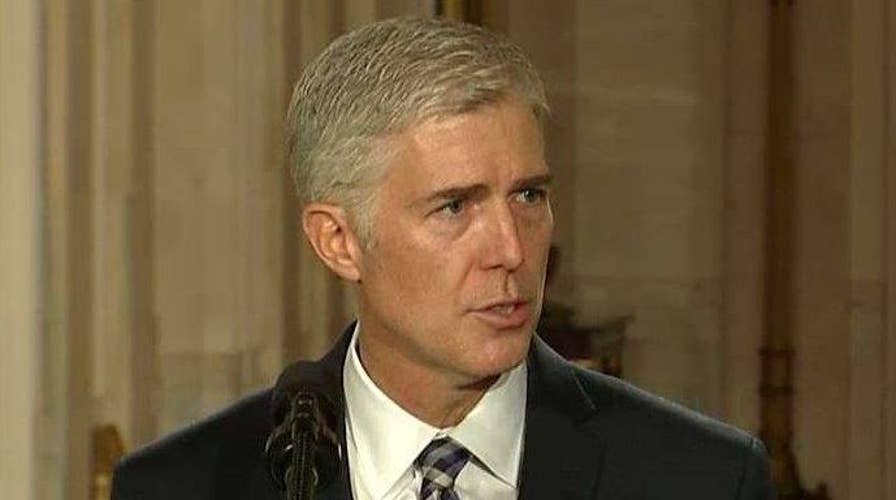

Neil Gorsuch: I am honored and I am humbled

President Trump's Supreme Court nominee speaks out

Judge Neil Gorsuch enters his Supreme Court confirming hearings Monday with legal credentials lauded by conservatives, but open to attack by liberals eager to undermine President Trump’s pick for the high court. However, his personal and academic histories are widely admired across the political spectrum.

Trump has described Gorsuch as "perfect in almost every way" for the high court.

Gorsuch, who goes before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Monday, is roundly described by colleagues and friends as a combination of wicked smarts, down-to-earth modesty, disarming warmth and careful deliberation.

Critics largely agree. But they don't think he belongs on the court, saying he's too quick to side with conservative and business interests at the expense of working Americans and the poor.

The 49-year-old Gorsuch has already served more than 10 years as an appellate judge in Colorado, styling himself in the mold of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, the conservative powerhouse whom he would replace.

Gorsuch is known for his plainly written opinions and his approach as a "textualist" who sticks within the boundaries of established law and precedent.

But some of his rulings and outside writings have led critics to say he tends to favor powerful interests over ordinary Americans.

They cite the case of a truck driver fired for leaving his trailer of meat on the side of an Illinois road after breaking down on a frigid night in 2009, fearing he'd freeze to death.

Among their other concerns is Gorsuch’s view on assisted suicide and euthanasia. He made clear in his 2006 book and other writings that he's not a fan.

Doctors, insurance companies and the healthiest in society, he argues, might wind up looking for ways to shorten the lives of the frail and the elderly to preserve resources for those with more promising futures.

His views on other controversial subjects, such as how widely the Second Amendment applies or whether abortion should be legal, are less known.

Gorsuch has not had a lot to say about abortion, either in his book or as a federal appeals court judge. However, he noted in the book that in the seminal Supreme Court abortion decision, Roe v. Wade, "a fetus does not qualify as a person."

Still, Gorsuch has academic credentials nearly beyond reproach, having attended Columbia University, Harvard Law School and Oxford University.

In his writings and lectures, Gorsuch presents himself as a "workaday judge," one wearing "honest, unadorned black polyester" robes from a uniform supply store.

He is described as the dad whose standing birthday present from his family is an agreement to watch a Western with him.

He's the sports nut who jogs with his law clerks, teaches them the Zen of fly fishing and waits at the top of the ski slopes to see which of them he'll need to help up after a fall.

"He's someone who knows the names of the security guards at the courthouse and gets to know who their families are," says former law clerk Theresa Wardon.

Luis Reyes, a former Gorsuch colleague at the Justice Department, says he “a glass-half-full kind of guy."

From his boyhood in Colorado, Gorsuch was a dutiful student, "always on the brainy side," says younger brother J.J. Gorsuch.

Theirs was a typical Western childhood, filled with family outings to go hiking, skiing and fishing.

He attended Georgetown Prep, an all-boys school in suburban Washington, after President Ronald Reagan chose his mother, Anne Gorsuch, a state legislator, to lead the Environmental Protection Agency.

She brought her three children east while her husband stayed in Colorado, as their marriage dissolved.

Gorsuch's friends at the Jesuit high school included Bill Hughes, whose father was a Democratic congressman from New Jersey.

Both felt pressure to protect his family name.

"We were all very cognizant of the responsibility we had to our parents not to screw up," Hughes remembers.

Gorsuch led schoolmates to the Capitol to attend a rally for insurgents opposing the Soviet Army in Afghanistan. His yearbook entry includes a joking reference to founding the "Fascism Forever" club, a dig at left-leaning teachers.

Most significant, he watched his mother's stormy 22-month tenure at EPA end with her forced resignation after being cited for contempt of Congress for refusing to turn over subpoenaed documents.

After high school, Gorsuch was in and out of Columbia in three years, though still found time to co-found a conservative newspaper and magazine.

He then went to Harvard Law without a break, before going off to Oxford to study legal philosophy, ducking out in the middle for a clerkship with Supreme Court Justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy.

In 1995, Gorsuch passed up job offers from big firms to work for a start-up, diving into "the muck and mess of real-life litigation," representing both plaintiffs and defendants, recalls former partner Mark Hansen.

He credits Gorsuch with a dogged work ethic -- billing an average 2,400-3,000 hours a year as partner -- but also an easygoing temperament.

After a decade in private practice, Gorsuch in 2005 joined the Justice Department, where he was deeply involved in lawsuits and legislative proposals supporting the George W. Bush administration's warrantless wiretapping program and its treatment of detainees at Guantanamo Bay and elsewhere.

From Justice, Gorsuch made a quick leap to the judiciary when Bush nominated him in 2006 for the 10th Circuit, a lifetime appointment and chance to get back to Colorado.

Fox News’ Bill Mears and The Associated Press contributed to this report.