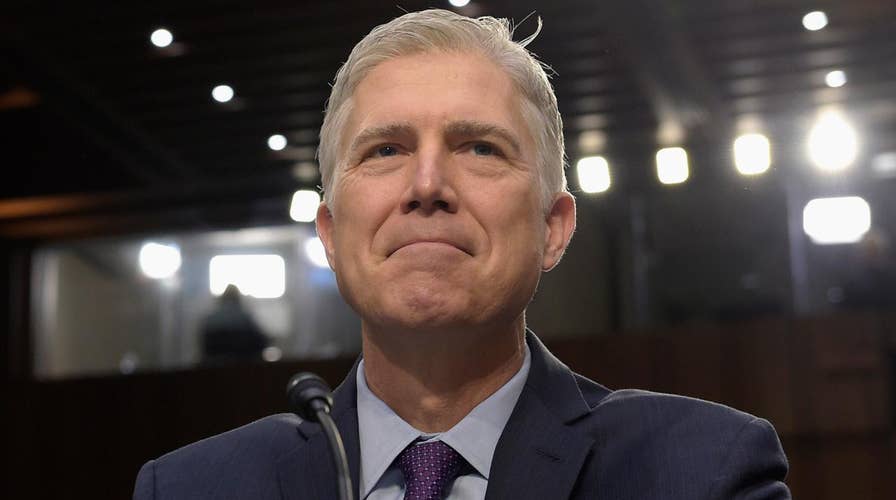

Religious liberty case brings first big test for Gorsuch

Judge Andrew Napolitano provides insight into the Supreme Court

A majority on the Supreme Court appeared to offer support Wednesday for a church excluded from a publicly funded aid program, during the hearing for what was considered Justice Neil Gorsuch’s first high-profile case.

At issue is a double dose of contentious issues: religious freedom and taxpayer funding. It is one of the most closely watched cases of the term, and could portend a series of upcoming church-state disputes facing the justices.

The justices are considering whether Trinity Lutheran Church in Columbia, Mo., should be eligible for state funds. The church sued after being denied funding to improve the surface of a playground used by its preschool, by replacing gravel with softer, recycled synthetic rubber.

The state program gives grants to nonprofits seeking a safer recreational environment for children. But Missouri's law -- similar to those in roughly three-dozen other states – prohibits direct government aid to educational institutions that have a religious affiliation.

Republican Gov. Eric Greitens’s unexpected decision last week to change the policy and allow religious institutions to participate in the program raised questions about whether the constitutional fight is now moot -- but no one on the nine-member bench appeared ready to punt the case away.

Instead, an intense hour of oral arguments focused on the merits.

"I'm not sure it's a 'free exercise' [of religion] question," said Justice Sonia Sotomayor. "No one is asking the church to change its beliefs. The state is just saying it doesn't want to be involved in giving [public] money to the church."

But other members of the court questioned the church's exclusion.

"You're denying one set of actors from competing [for the grant money] because of religion," Justice Elena Kagan said. She called it a "clear burden on a constitutional right."

The Constitution's First Amendment speaks on religion in the public sphere with two important provisions. The Establishment Clause prohibits the government from unduly preferring or promoting religion over non-religion, and vice versa. And the Free Exercise Clause protects Americans' rights to practice their faith, absent a "compelling" government interest.

Gorsuch, the court’s newest member, was subdued by comparison to his active involvement during his first two days of arguments. He only asked a couple brief questions of the state's lawyer near the end of arguments.

The Supreme Court accepted the church's petition for review back in January 2016, when Justice Antonin Scalia was still the senior conservative. His death a month later kept the case on hold, possibly because the eight justices believed they would ultimately tie. Such splits mean no nationwide precedent is set.

Trinity Lutheran's high-profile case was finally put on the argument schedule for April, just in time for Gorsuch to perhaps cast the deciding vote.

The Christian church operates its Child Learning Center to serve families, incorporating "daily religion and developmentally appropriate activities in a preschool program."

To minimize injuries on its playground, the church applied to the state's "Scrap Tire Surface Material Grant" program, funded by a 50-cent tax on the purchase of new tires. The church says its application ranked fifth out of 44 other nonprofits, but was ultimately denied.

Missouri's constitution says "no money shall ever be taken from the public treasury, directly or indirectly, in aid of any church, section or denomination of religion."

The high court has never fully answered whether "free exercise of religion" compels states to provide taxpayer funds to religious institutions, through neutral means that do not promote faith-based beliefs or practices.

Teachers unions, meanwhile, worry a ruling favoring Trinity Lutheran would add nationwide momentum for private school voucher programs, part of the school-choice movement which the Trump administration has promoted. And some organizations fear a sweeping conservative-majority court opinion would lead to discrimination with the backing of government money.

Into the debate jumped Gorsuch, who took heat from Senate Democrats during his confirmation over past cases dealing with religion, while serving as a federal appeals court judge in Denver for over a decade.

Perhaps the 49-year-old justice's highest-profile case was the 2013 concurrence supporting the right of for-profit, secular institutions (and individuals too, he argued) to oppose the Obama's administration mandate to provide contraceptives to their workers. Gorsuch affirmed his past ardent commitment to religious freedom against claims of government "intrusion."

Besides the Trinity case at hand, the Supreme Court in coming days could accept two other religious liberty disputes for future review: Whether a Colorado baker and a Washington state florist can be compelled to do business with same-sex couples, which they say would violate their "sincerely held" religious beliefs.

The current case is Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (15-577). A ruling is expected in late June.