Chuck Schumer pays tribute to late Sen. Fritz Hollings of South Carolina

New York Senator pays tribute to late Sen. Fritz Hollings of South Carolina.

Nobody talked like the late Sen. Fritz Hollings, D-S.C.

Nobody sounded like Fritz Hollings.

"When it comes to Senator Hollings, they broke the mold," observed Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., in a statement. "Fritz was a giant of a man who was often called the 'senator from central casting.'"

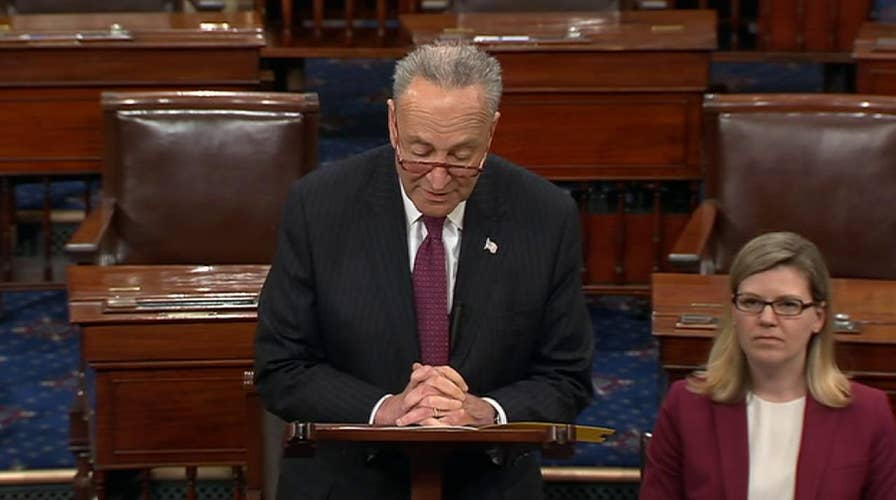

"He was an original," said Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y.

Fritz Hollings died over the weekend at age 97. Hollings was tall, standing about 6'3". He was topped by a shock of sleek, white hair, always demarcated by a crisp part on the left. Always dressed impeccably, in tailored, pinstripe suits.

Hollings just looked like a senator.

And then there was the voice.

The pipes were what really distinguished Hollings. His voice was deep like a hollowed-out, Lowcountry well. The result was a resonant, rich, southern drawl. When Hollings spoke, he just sounded the way you thought a senator from South Carolina would sound. Think Foghorn Leghorn crossed with James Earl Jones.

And when Hollings took the floor, everything in the Senate stopped. You couldn't ignore him. Hollings would prowl around his desk near the rear of the Senate chamber. Hollings didn't need props. He didn't need a stack of papers. Hollings just had his own, 100-watt sound system. The senator would thunder from the back of the Senate and his voice would rattle the copper spittoons which remain on the floor in front.

"If this budget is balanced, I'll jump off the Capitol Dome!" Hollings once cried during a speech about fiscal discipline in the mid-1990s. He stretched out the word "dome" into a polysyllabic melody.

Hollings then proceeded to upbraid his colleagues who would "ride around the countryside in limousines," describing the entire affair "a grand farce."

Only, Hollings didn’t quite say "farce." He stretched out the word "farce" like a grade-school kid playing with slime. There was no discernable "r" in Hollings’s enunciation.

Hollings served in the Senate from 1966 through 2005. But despite his lengthy tenure in Washington, Hollings was South Carolina's junior senator for all but the final two years of his career. That made Hollings the longest-serving junior senator in U.S. history. Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., arrived in the Senate in 1954, and after a seven-month gap in 1956, never left until he retired at age 100 in January 2003. Thurmond's longevity always blocked Hollings when it came to seniority.

Skyrocketing federal spending was Hollings' key issue. He teamed with then-Sen. Phil Gramm, R-Texas, and the late Sen. Warren Rudman, R-N.H., to create a balanced budget plan called "Gramm-Rudman-Hollings" in 1985. You may have heard of "sequestration," the package of mandatory spending cuts imposed by the debt ceiling deal of 2011. Sequestration lingers to this day over what Congress terms as "discretionary" spending. However, Gramm-Rudman-Hollings was the original version of sequestration. It canceled spending, preventing Congress from exceeding certain fiscal ceilings.

The House and Senate approved Gramm-Rudman-Hollings in 1985. But the Supreme Court case Bowsher v. Synar found the automatic cuts to be unconstitutional. The argument was that Gramm-Rudman-Hollings ceded spending authority to the executive branch. Senators retooled the plan in 1987, but it never resulted in smaller deficits. Hollings later lopped off his surname from the legislation, saying the revised effort lacked teeth.

As much as you remembered Hollings' voice, people often recalled what he said – for good or ill.

Congressional Republicans frequently pushed for tax cuts. Hollings often suggested that the government really needed a tax increase to balance the books.

Hollings sought the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984. "Shoot all the economists," he said. "Shoot all the pollsters." It wouldn't have helped. Hollings dropped out of the race after a poor showing in New Hampshire.

Hollings once referred to then-Sen. Howard Metzenbaum, D-Ohio, as "the senator from B'nai B'rith." Metzenbaum, who was Jewish, took issue with the South Carolinian's characterization of him and the Jewish service organization. Hollings later apologized and the language was stripped from the Congressional Record.

When discussing an international trade meeting in Switzerland, Hollings said that "these potentates down from Africa, you know, rather than eating each other, they'd just come up and get a good, square meal in Geneva."

Hollings chaired a Commerce Committee hearing about violence on TV in the early 1990s.

"What is it? Buffcoat and Beaver or Beaver and something else?" Hollings said at the hearing, referring to MTV's animated ne'er-do-wells Beavis and Butt-Head. "I don't watch it. But whatever it was, it was on at 7. Buffcoat. And they put it on now at 10:30."

Current South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster ran against Hollings for Senate in 1986.

“I’ll take a drug test if you’ll take an IQ test,” snapped Hollings during one contentious exchange.

Hollings prevailed with 63 percent of the vote. But McMaster and former Vice President Joe Biden will both speak at Hollings's funeral next week. Hollings will also lie in state in the South Carolina statehouse.

When Hollings was on his way out from the Senate in 2005, he noted that a letter to the editor of a local paper declared "'We hope Hollings enjoys his retirement, because we sure as hell will.'"

Bipartisan members of South Carolina's House delegation assembled in the well of the House chamber Monday evening to pay tribute to Hollings. House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn spoke about Hollings's push for desegregation while serving as South Carolina governor.

Clyburn says he first met Hollings in 1960, when Clyburn was organizing sit-ins. Hollings invited Clyburn to his office.

"He gave me a great lesson that day in politics," said Clyburn, saying that even to this day, he's not spoken publicly about some of the kernels of wisdom Hollings passed along.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Clyburn said that in 1962, just before Hollings was to finish his term as governor, the courts ruled that Clemson University had to integrate.

"Fritz spoke to the legislature and said to them on that day, 'We have run out of courts. And we are going to be a nation of laws,'" said Clyburn.

Fritz Hollings may have fallen silent. But to Clyburn and others, the voice still echoes.