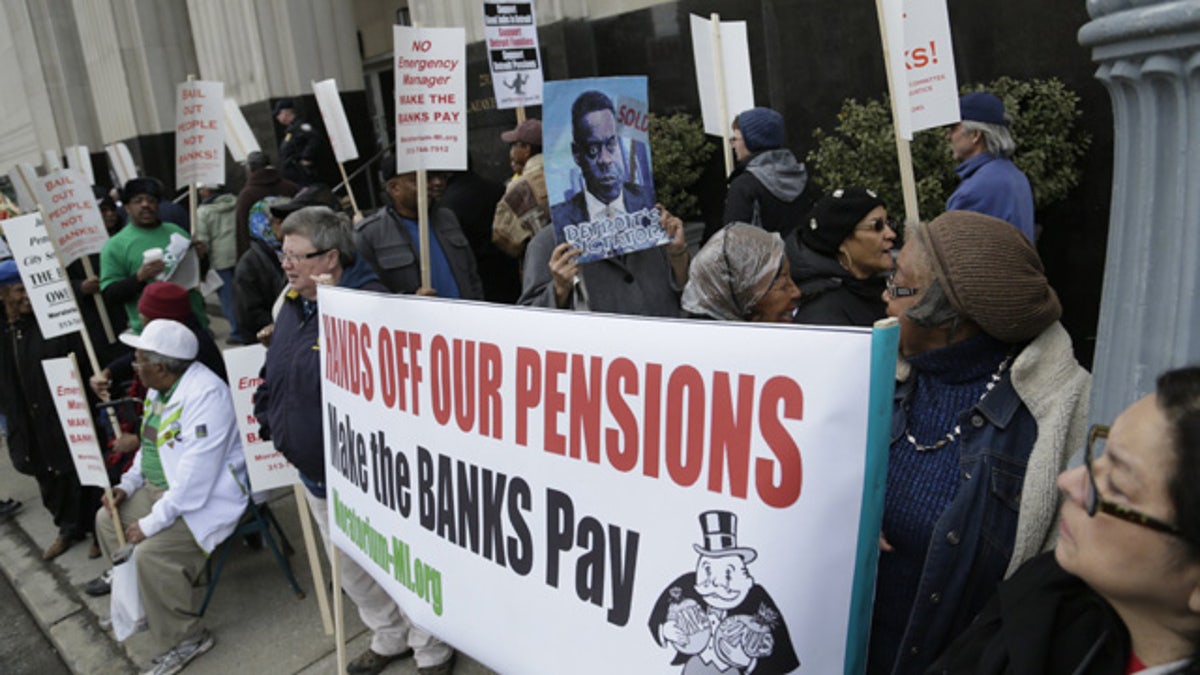

April 1, 2014: Protestors against deeper cuts in pensions march in front of the Theodore Levin Federal Courthouse in Detroit. (AP Photo/Detroit Free Press, Mandi Wright, File)

LANSING, Mich. – The Michigan Legislature's $195 million lifeline to help prevent steep cuts in Detroit's pensions and the sale of city-owned art is being hailed as a major step forward in ending the largest public bankruptcy in U.S. history.

The state funds will join commitments from 12 foundations and the Detroit Institute of Arts to shore up Detroit's two retirement systems. The city's art museum and its assets would be transferred to a private nonprofit.

A delighted Republican Gov. Rick Snyder and allies are hoping Tuesday's approval of the state money will immediately persuade tens of thousands of retirees and city workers to get behind the unusual pension and art rescue. They are in the midst of voting on the deal their leaders -- and now lawmakers from both parties -- have endorsed.

"I clearly encourage everybody to vote `yes,"' the governor said during a news conference. "A protest vote is not helpful."

While there are many moving parts to state-appointed emergency manager Kevyn Orr's restructuring plan, the pension agreement is viewed as a centerpiece. If the retirees and employees do not support it, $816 million from the state, foundations and the Detroit Institute of Arts would vanish and deeper pension cuts could become inevitable.

The trial on the city's case will be held this summer.

"This has been unbelievable," U.S. District Judge Gerald Rosen, the chief mediator between the city and its creditors, said of legislators coming through with the financial package.

Despite conservative groups' opposition to bailing out Detroit, the Republican-led Senate voted 21-17 to pass the main bill allocating the $194.8 million.

Snyder said he will sign the legislation in a day or two.

"This is a good solution. This is a way we can support one another and again make it Detroit, Michigan, instead of Detroit versus Michigan," he said.

By backing the deal, the governor and legislators are hoping to avoid a protracted bankruptcy and the potential for city retirees to fall into poverty, which could cost the state an estimated $270 million in social safety net costs over 20 years. They also say that Michigan as a whole cannot succeed unless its largest city is turned around.

"This is by far, in my opinion, the best that we're going to be able to do," said Senate Majority Leader Randy Richardville, R-Monroe.

Bond insurers have pointed to the art collection -- which includes Van Gogh's "Self Portrait" -- as a possible billion-dollar source of cash in the 10-month-old bankruptcy case. The city firmly opposes that, and instead is banking on the separate deal brokered by mediators that would protect the art forever and limit base pension cuts to no more than 4.5 percent instead of as much as 26 percent.

The up-front state payment, the equivalent of $350 million spread over 20 years, would come from the state's savings account and would be repaid with annual $17.5 million withdrawals from Michigan's tobacco settlement over 20 years. A state-dominated board would oversee the city's finances for as few as three years or for decades, depending on whether its books are balanced.

Sen. Coleman Young II, D-Detroit, said the bills would keep the city "under the rule of unelected cronies for Lord knows how long."

And Sen. Patrick Colbeck, R-Canton Township, pointed to financial problems in Wayne County -- which includes Detroit -- and other cities such as Flint and Highland Park.

"Are we going to dip into the rainy day fund to bail out all these communities?" he said. "We continue to box ourselves into dead-end solutions that lead to bigger government."

Among those supporting the legislation was Ryan Plecha, a lawyer for the Detroit Retired City Employees Association, who said members are seeing reduced health care benefits and sharply rising out-of-pocket costs and stand to see a 4.5 percent pension cut and no cost-of-living increases. As part of the deal, retiree groups will withdraw pending lawsuits and release Michigan from future claims that retirees are owed their full pensions under the state constitution, he said.

"Honestly, it would be easier to recommend a fight to the end. But that is not in the best interest of retirees," Plecha said.