Fight over Kavanaugh could impact Heitkamp's re-election bid

New polling shows 10 point lead for Republican Kevin Cramer in his race to unseat North Dakota Senator Heidi Heitkamp; insight from Amy Walter, national editor at The Cook Political Report.

North Dakota Sen. Heidi Heitkamp did not push to prosecute individuals responsible for physical and sexual abuse of students when she was the state's Attorney General, with one accused school employee subsequently sexually assaulting a child.

Heitkamp, who served as the North Dakota’s attorney general between 1992 and 2000, oversaw the North Dakota Bureau of Investigation’s probe between 1993 and 1994 into allegations of abuse at the Wahpeton Indian School (WIS), now known as the Circle of Nations School, a boarding school for troubled Native American students.

She is currently running for her re-election in the upcoming November election, with the latest Fox News poll putting Republican candidate Kevin Cramer ahead by 12 points. Last week she justified her vote against Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation, stating she will stand up for women and young girls across the country. “Our actions right now are a poignant signal to young girls and women across our country,” Heitkamp said. “I will continue to stand up for them.”

The allegations of physical and sexual abuse at the Native American school were largely confirmed by four state and federal investigations conducted by the North Dakota Attorney General’s Office, the North Dakota Department of Human Services, the FBI, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

But despite the investigations and the corroboration of the allegations, none of the government agencies, including the office led by Heitkamp, recommended pursuing charges against individuals who allegedly committed the crimes.

In a 1994 memo written by Heitkamp, she cited State Attorney Earle “Bud” Myers’s opinion that no charges should be pressed against individuals who allegedly committed the crimes. Heitkamp didn’t press to revisit the case and pursue the allegations.

In a statement to Fox News, Heitkamp’s campaign denied she did not do enough to prosecute.

“As the state’s top law enforcement officer, Heidi took all of the action within her jurisdiction, including recommendations to improve conditions at the school and has continued work for our Native communities in the Senate,” the senator’s press secretary Sean Higgins said.

"As the state’s top law enforcement officer, Heidi took all of the action within her jurisdiction, including recommendations to improve conditions at the school and has continued work for our Native communities in the Senate."

The campaign also provided a statement from Lyle Witham, a former North Dakota Assistant Attorney General who worked also worked under Heitkamp, who said only State’s Attorneys determine whether to prosecute a crime and the attorney general “does not have the legal authority to press charges in criminal cases.”

But attorneys Fox News spoke with said the campaign’s comments are a convenient excuse and ignore the reality of how state attorney generals operate.

“A state attorney general is the lead law enforcement officer in the state. If they want to bring a case, they are not going to be stopped by a county attorney’s recommendation,” a trial attorney and former U.S. Department of Justice official told Fox News.

"A state attorney general is the lead law enforcement officer in the state. If they want to bring a case, they are not going to be stopped by a county attorney’s recommendation."

“Maybe they will be stopped by the federal government, but I’d be shocked to learn that it works upwards, where a county prosecutor or a local prosecutor gets to dictate what the state attorney general does,” he continued. “Most lead prosecutors that make their way up to that level of influence and power will find a way.”

The former DOJ official said state attorney generals sometimes don’t take up cases if they fear they might not succeed, which could then damage to them politically and their future political aspirations. “But if you’re a bulldog prosecutor you could care less about that. If it’s an important enough case, you’ll find a way to make it work,” he added. “The idea that some county prosecutor or state attorney says ‘hey, this is our case’ – this is just not how it works.”

“You have to bully pulpit as the attorney general in the state. Just like when you’re the attorney general of the United States, you may not necessarily have direct authority to do something, but you can certainly go out and put pressure on local jurisdictions to prosecute cases,” he added.

"You have to bully pulpit as the attorney general in the state. Just like when you’re the attorney general of the United States, you may not necessarily have direct authority to do something, but you can certainly go out and put pressure on local jurisdictions to prosecute cases."

Josh Helton, a Washington attorney with state criminal experience also dismissed the campaign’s explanation. “It would be very unusual for a state attorney general not to have broad investigative and prosecutorial discretion.”

He pointed to the North Dakota Century Code that allows the state attorney general to “consult with and advise” state attorneys “in matters relating to the duties of their office.” The state AG can also “attend the trial of any party accused of crime and assist in the prosecution when in the attorney general's judgment the interests of the state require it.”

The two particular laws in the code indicate what Heitkamp could have done, Helton said. “I would say it’s in the best interests of the state” to prosecute an individual who committed crimes against “a historically disadvantaged population, socio-economically disadvantaged children.”

He added Heitkamp could have also used her authority to “persuade” state attorneys to charge the individuals.

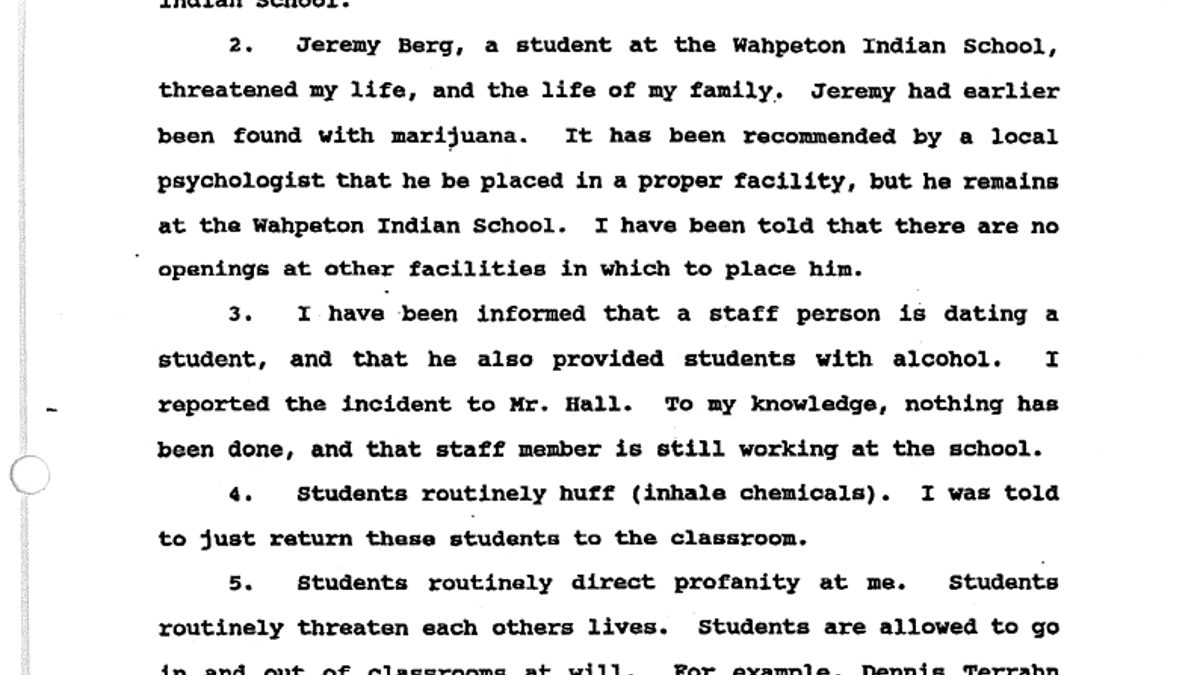

One former counselor, John Allery, said he reported another staff member for dating a student and providing alcohol to other students, yet no actions were taken. (John Allery, Affidavit Alleging Child Abuse and Neglect at Wahpeton Indian School, 11/11/93)

The school staff members detailed various allegations of abuse, including physical and sexual abuse, inadequate medical care, and other claims of negligence in a wrongful termination lawsuit against WIS Superintendent Robert Hall, who resigned from his post in 1995.

The administration allegedly “ignored” a student who claimed she had been inappropriately touched by another staff member. One former counselor, John Allery, said he reported another staff member for dating a student and providing alcohol to other students, yet no actions were taken.

Other staffers detailed subpar medical care and physical abuse, including slapping other students and giving students so-called “swirlies” that involves holding an individual upside-down with his head in the toilet while flushing it.

A WIS student also said Blaine Buss, a former dorm matron who was convicted of felony assault for nearly choking his wife to death before his employment at the school, “threw him against his bedroom wall and hit him in the face.” Buss and another staffer, David Keehn, also abused two other students, with one student subsequently diagnosed with a fractured cheekbone, according to the probe by the Bureau of Criminal Investigation.

Just a few months later after the end of the investigations and the decision not to prosecute anyone, Buss went on to sexually assault a child. He charged with two counts of gross sexual imposition against a child under the age of 15 in August 1994 and was subsequently sentenced for both counts.