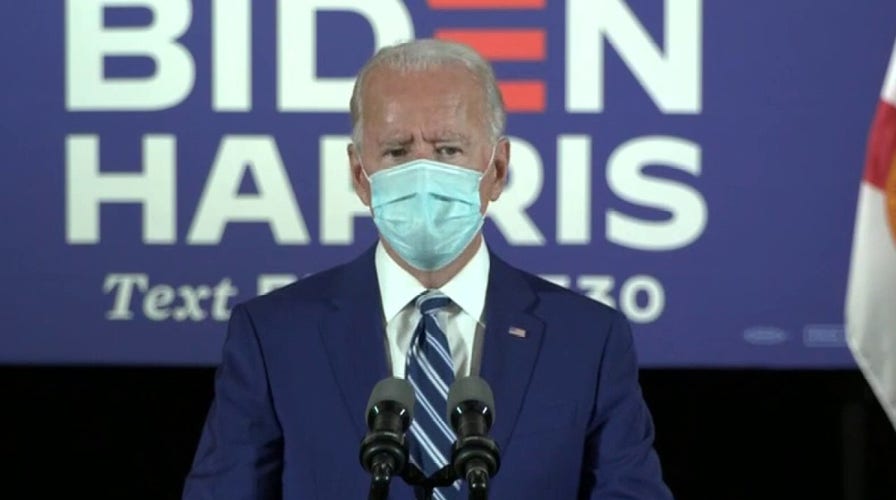

Joe Biden acknowledges past court-packing position

Democratic nominee travels to Florida to make his pitch to seniors; Peter Doocy gives an update on 'Special Report'

The concept of adding more seats to the U.S. Supreme Court – or so-called “court packing” – has become a central part of the discussions in the weeks leading up to the presidential election, particularly with Vice President Joe Biden declining to address the issue.

Earlier this month, the Democratic candidate said voters will know his opinion on the matter “when the election is over.”

If Biden and a Democratic-held Senate were to add more judges to the Supreme Court, they could flip it to the left, and reverse what they say are ill-gotten Republican gains on the court.

But observers of international governance warn that adding court seats has been attempted in other countries, often with disastrous results.

"You need to look at what has happened in other countries... don't touch the Supreme Court," Antonio Canova, a constitutional law professor at Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Venezuela, told Fox News via a translator.

Nowhere is the history clearer than in his socialist country, Canova said. Venezuela's constitution follows the same basic structure invented by the Founding Fathers of the United States - with an executive branch, a legislature, and a Supreme Court.

Pedestrians walk past a mural depicting the late President Hugo Chavez, in Caracas, Venezuela, Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2019. (AP Photo/Leonardo Fernandez)

When the late Venezuelan socialist leader Hugo Chavez first won the election in 1999, the country's Supreme Court was independent. But after it issued several rulings that went against him and his administration, Chavez packed the court by passing a law expanding its size from 20 to 32 justices in 2004. Chavez got to pick the 12 new judges -- effectively stacking it in his favor.

Canova, who compiled research on 45,000 rulings issued by Venezuela's high court since 2004, says the court never sided against Chavez's government after it was packed.

"Since 2004, I found that Chavez and the government never lost a case. Not a single one," he said.

Canova says he hopes people in the United States can learn from what happened to Venezuela’s institutions.

VENEZUELA'S MADURO DENOUNCES US AS “THE MOST SERIOUS THREAT TO WORLD PEACE” IN UN ADDRESS

It was only after Chavez stacked the court that, in 2006, he ran on a fully socialist platform. When he won re-election that year, the justices of the Supreme Court stood and chanted a rhyme to the effect of "great, Chavez is not leaving!"

After Chavez's 2006 win, he began confiscating thousands of private businesses – including media outlets, oil and power companies, mines, farms, banks, factories, and grocery stores.

"They basically took over the entire economy," Canova noted.

One video shows a shop owner in tears as his business was confiscated.

"Without control of the court, they wouldn't have been able to do any of this," Canova said. "The government had no fear of legal repercussions for their actions. So since 2004 the government has taken out opposing political parties, they have taken political prisoners, they have taken over businesses... it's like the wild west."

When Chavez died of cancer in 2014, he handpicked his successor, Nicolas Maduro, a former bus driver who continued the same hard-line socialist policies.

The government’s takeover of the economy, combined with a plunge in oil prices, transformed a country once hailed as the richest in Latin America to one plagued with mass unemployment, starvation, rampant crime and hyperinflation that broke 10 million percent.

It was that climate of decline which saw angry Venezuelan voters overwhelmingly turn out against the socialist party at the 2015 midterm elections. Opposition parties won a shocking super-majority (two thirds) in the National Assembly -- or congress -- which should have enabled them to override Maduro.

But before the new legislators took office, the outgoing socialist-controlled legislature hurriedly replaced 13 Venezuelan Supreme Court judges whose terms were running out in what Canova called yet another case of packing the court.

When the new legislature was seated, the re-stacked court started stripping it of powers, even declaring that the embattled Maduro had the power to change existing laws without getting the changes approved by the legislature.

Zoraida Silva, 26, feeds her six month baby Jhon Angel, at a soup kitchen in The Cemetery slum, in Caracas, Venezuela. Silva said that she can not afford to have 3 meals a day, and she has been eating at the soup kitchen for two years ago. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

The Supreme Court's actions reached absurd levels. In 2017, it declared that the legislature was illegitimate and that all its powers would be transferred to the Supreme Court itself.

That ruling sparked riots throughout Venezuela, as well as denunciations from neighboring countries. The backlash forced the court to back down.

But despite pulling back from that ultimate power grab, the high court still allowed Maduro to rule without consulting the legislature.

In the country's 2018 presidential election, all serious opposition candidates for president were either jailed or banned from running, and Maduro won reelection easily. The election was declared illegitimate by the United States, the European Union, and the Organization of American States (OAS), which represents all countries in the Americas.

On Maduro's inauguration day following that election, the opposition-held legislature declared that Maduro was no longer the rightful leader and that Juan Guaido, the legislature's speaker, was taking over as president.

That set off a near-civil war in Venezuela, with both Guaido and Maduro currently claiming to be the country’s rightful leader. Maduro retains practical control of the military and the country as a whole, while Guaido is recognized as the president by dozens of countries, including the U.S.

"Venezuela is a warning to what could happen in the US," Canova said.

VENEZUELAN PRESIDENT MADURO PARDONS MORE THAN 100 POLITICAL OPPONENTS

But while it is a cautionary tale, he noted that the United States has a culture that could keep the damage of court packing well below Venezuelan levels. He pointed to a long tradition of skepticism towards government power in the U.S.

“But if people start thinking that the power of the government is benevolent, things will go down a bad path," Canova said.

Venezuela is also not the only cautionary tale about Supreme Court packing. It's been tried in many countries.

Human Rights Watch noted in 2004 -- as part of its condemnation of Chavez's first court packing -- that, "During the 1990s Argentina's president, Carlos Menem, severely undermined the rule of law by packing the country's Supreme Court with his allies."

Menem expanded Argentina's high court from five justices to nine, in order to prevent the court from striking down his plans to confiscate businesses. Within a decade, the South American country entered the "Argentine great depression."

In Peru, former President Alberto Fujimori "went even further in controlling the courts through mass firings and denial of tenure to judges," Human Rights Watch noted. This triggered a "subsequent meltdown of democracy."

In this March 15, 2018 file photo, Peru's former President Alberto Fujimori listens to a question during his testimony in a courtroom at a military base in Callao, Peru. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia, File)

The concept of court packing actually is not new in the U.S. In the 1930s, former President Franklin Roosevelt proposed it after the Supreme Court struck down his biggest "New Deal" plans, including government price controls.

Roosevelt wanted to add six new justices. But the plan fell apart, as the Senate Judiciary Committee -- even though it was Democrat-controlled -- declared the plan “an invasion of judicial power such as has never before been attempted in this country.”

Roosevelt's plan was defeated in the Senate by a vote of 70 to 20.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

At present, a handful of Senate Democrats have expressed opposition to stacking the court — including Joe Manchin of West Virginia, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, and Dianne Feinstein of California.

But many others support adding justices, or decline to answer, such as Minnesota incumbent Tina Smith.

Her Republican challenger, Jason Lewis, condemned that lack of an answer and told Fox News that court-packing threats were "an assault on the constitutional separation of powers ... a 'clear and present' danger to our very system of government."

Maxim Lott is executive producer of Stossel TV and creator of ElectionBettingOdds.com. He can be reached on Twitter at @MaximLott.