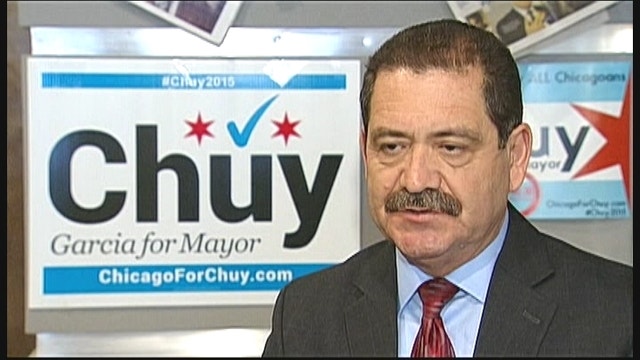

Emanuel must prepare for a runoff election against ‘Chuy’ Garcia

Mayor Rahm Emanuel must prepare for a runoff election against opponent 'Chuy' Garcia after he failed to win the majority needed to avoid it.

While Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel may be a household name throughout the United States thanks to his time in Congress and as the former Chief of Staff under President Barack Obama, his challenger for the post is a virtual unknown outside the Second City.

Even so, with nearly all the votes counted, Cook County Commissioner Jesus "Chuy" Garcia, managed to get 34 percent of the Democratic primary vote, only 11 points behind Emanuel. Three other candidates divided the rest.

Over the past 30 years, Garcia has become an integral part of Chicago – and Illinois – politics, holding alderman and commissioner posts as well as becoming the first Mexican-American elected to the state senate, where he served two terms.

"Nobody thought we'd be here tonight," Garcia said Tuesday night after forcing a run-off election with Emanuel. "They wrote us off, they said we didn't have a chance. They said we didn't have any money, while they spent millions attacking us. Well, we're still standing. We're still running. And we're gonna win."

The 58-year old Garcia moved with his parents when he was 10 to United States from Los Pinos in Mexico, a town of about 200 people in the state of Durango. The youngest of four children, he moved to Chicago’s blue-collar, Latino neighborhood of Pilsen in 1964 after his father – who had picked fruit in Texas and California – gained legal residency and landed a job at a cold-storage facility.

Living in Pilsen was "the most powerful civics lesson one could get," Garcia said.

He had to sidestep gangs, racism and discrimination during his time in the neighborhood before his family moved to the Little Village neighborhood in 1969. When they moved, the family found themselves the only Latinos on the block, but just ten years later the area was 74 percent Hispanic.

While Garcia credits Latinos with saving Little Village, at first there was a good deal of racial tension between the newcomers and old residents.

"We got called spic, wetback, taco bender," he told the Chicago Reader. "That was the funniest one to me. I guess it had to do with the hard shells they sell for tacos. But 'taco bender'? Do you think people sit around and bend it and shape it and package it?"

After graduating from Saint Rita High School while working the night shift at Brach's candy factory, Garcia enrolled at the University of Illinois's Chicago campus and began his career in political activism. While there, he helped bring about the creation of a Latin American Cultural Center at the school and began to visit shops to talk with workers about conditions and to urge them to unionize.

After college, Garcia became heavily involved in city politics, managing the campaign of his close friend, Rudy Lozano, when he ran for alderman in 1983 against the 22nd ward's longtime incumbent, Frank Stemberk. Lozano lost by only 37 votes; a few months later, he shot and killed in his home at the age of 31 by a teenage gang member.

The new mayor of Chicago – and its first African-American one – Harold Washington took notice of Garcia and appointed him deputy commissioner of the water department.

In 1986, Garcia was elected to the Chicago City Council as alderman himself, where he continued to work with Washington. In 1992, he continued his political rise by becoming the first-ever Mexican-American elected to the Illinois senate, where he served two terms.

After he left the senate, he founded Enlace Chicago, a nonprofit community development organization in Little Village, where he remained until 2009. The organization made headlines in 2001 when it led a nearly three-week hunger strike by parents who were trying to get city school officials to fulfill a long-delayed promise to build a high school in Little Village.

In 2010, Garcia was elected Cook County Commissioner.

"He's an odd bird in the sense that he's got two traits you rarely find in politicians these days, which are honesty and humility," said Maurice Sone, an attorney who runs a community group in Little Village, told the Chicago Tribune. "Don't let his soft demeanor surprise you.... He's not confrontational. He just has a different way."

The mayoral campaign has been a grind, but Garcia, despite being dubbed "an accidental candidate’ by the Chicago Tribune because progressive liberals in the city only took up his cause after two other candidates dropped out of the mayoral race, is hopeful of his chances going up against the well-known incumbent.

"We were up against huge amounts of money and people with power who lined up to protect the status quo," Garcia said. "Voters rejected that. They want a deeper debate, and we intend on giving them that. We're very enthused that the voice of ordinary Chicagoans is being heard and that, as we move forward, it bodes well for Chicago's democracy."

With nearly all the votes counted on Tuesday, Emanuel had 45 percent, Garcia 34 percent, and the three other candidates divided the rest.

During the campaign, Garcia played on discontentment in Chicago's neighborhoods, where frustrations linger over Emanuel's push to close dozens of schools. They also criticized Emanuel's roughly $16 million fundraising effort — more than four times that of his challengers combined — and his focus on improvements to the city's downtown business district.

"We're looking forward to round two and a good set of debates, hopefully," Garcia said. "We'll have a chance to drill down deeper into the issues, and of course, we're going to talk about the future of the city and how we can include all of the neighborhoods and the people of Chicago in the process of redirecting the direction of the city."

As he has done throughout his political career, Garcia is hoping that his appeal with Chicago's working class and minority voters will sway the polls in his favor come April's run-off election.

"Working class folk who stepped up in this campaign feel that Chicago needs to be responsive to the neighborhoods and toward ordinary people and we delivered. It may be the retooling of a Democratic coalition, maybe with a small 'd.'" he said.

While the city's minority populations have grown and changed, Garcia's approach harkened comparisons to his mentor's campaigns. Three decades ago, Washington relied on coalescing black and Latino support to win the mayor's seat. The difference now is that voters, particularly younger ones, are more willing to cross racial boundaries to support a candidate.

"There is a much more diverse multicultural youth base ... this is what their life experience is," said Sylvia Puente, executive director of the Latino Policy Forum. "They resonate with the candidate."

Emanuel's support is strongest in the city's downtown and on its North Side, home to some of Chicago's more affluent neighborhoods. Garcia did well on the West Side, particularly in heavily Hispanic areas.

The mayor lost support in the city's largely African-American wards on the South Side compared to his first election in 2011. He headed there first thing Wednesday morning, shaking hands with commuters at a train station before addressing voters at a senior center.

Emanuel said the spring runoff will be about which candidate has the "plans and the perseverance" to make progress in the city.

"It's no longer a multiple choice," he said. "It's a clear choice between two different visions of the future and how to get there. One way is about the old politics of deferral. And one is about confronting our challenges head-on by being clear about what they are, being honest and forthright about the choices we have to make."

Garcia has drawn on his contacts with community organizers and on support from the Chicago Teachers Unions, whose leader, Karen Lewis, considered a mayoral bid before being diagnosed with a brain tumor. Garcia also had the backing of national progressive groups such as MoveOn.org and Democracy for America, a political action committee started by former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean.

Puente said Garcia's grassroots connections were effective from the beginning, gathering roughly 60,000 signatures in a matter of days to help him get on the ballot.

Political consultant Delmarie Cobb, who opposed Emanuel's re-election, said Garcia will now get national attention from media and outside groups which will help counteract Emanuel's millions of fundraising dollars.

"The mayor is weakened, and it's anybody's ball game," Cobb said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report