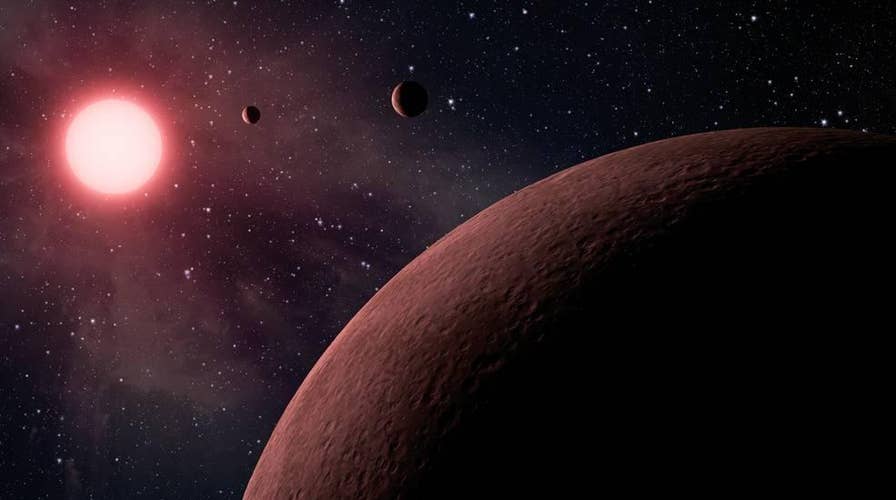

NASA finds 10 planets that could support life

On 'America's Newsroom,' Space.com's Tariq Malik offers insight on data found on telescope

The sun is like a teenager that cycles through mood swings – from dramatic to chill and back again – roughly every eleven years. But this time it’s different. It now appears the sun is heading for a rare, super-chill period that threatens to add some unexpected drama to today’s climate change discussion.

For most of its history, science believed the sun’s output was constant. It was wrong. Today, we realize that lots of things about the sun wax and wane every eleven years, most notably its brightness and the number of explosive disturbances on its surface called sunspots and faculae.

That’s not all. The eleven-year cycle itself snakes up and down like a roller coaster, reaching “grand maxima” and “grand minima” every 100-200 years. The last grand maximum peaked circa 1958, after which the sun has been steadily quieting down. Today, the drop in activity is at its steepest in 9,300 years.

Is the sun headed for a grand minimum? If so, it immediately calls to mind the famous Maunder Minimum, during which the sun languished for seventy years. From 1645 to 1715 the sun’s brightness dimmed by a fraction of one percent and the number of sunspots and faculae plummeted to nearly zero.

On top of that, the Maunder Minimum occurred precisely during the coldest part of the centuries-long Little Ice Age, when the average temperature of the northern hemisphere dropped by about 1.1 degrees Fahrenheit. Was it a coincidence? Or did the Maunder Minimum help drive the ice age? Here’s where the story about today’s apparent plunge toward a solar grand minimum really heats up.

According to NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Earth’s temperature has increased by about 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880, roughly the end of the Little Ice Age. The worst warming is yet to come, most scientists claim, and not even a grand solar minimum will prevent it.

Using computer simulations, scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, estimate that “a grand solar minimum in the middle of the 21st century would slow down human-caused global warming and reduce the relative increase of surface temperatures by several tenths of a degree [Celsius, equal to about 0.5 degrees Fahrenheit].” But at the end of the grand minimum, they say, the warming would simply pick up where it left off. “Therefore … a grand solar minimum would slow down and somewhat delay, but not stop, human-caused global warming.”

But the sun’s dramatic quiescence comes with a surprising complication: cosmic rays. They are subatomic particles – mainly protons and helium nuclei – that originate from somewhere deep within our galaxy. Their source is still a mystery.

Usually, the sun’s powerful magnetic field and radioactive winds keep cosmic rays away from our neighborhood. But when the sun weakens, the cosmic rays are freer to move in and bombard Earth. New research shows that upon striking the atmosphere, cosmic rays produce showers of particles and ions that seed clouds with extraordinary efficiency. The increased cloudiness shades Earth from the sun.

Recently, a team of Russian scientists compared the cosmic-ray cooling mechanism to two other well-known drivers of climate change – the sun’s inconstant brightness and greenhouse gases. Publishing in the "Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Physics," they maintain the cosmic-ray cooling phenomenon will dominate everything else in the coming decades and actually force a period of global cooling.

It is a radical hypothesis, to be sure, but even mainstream scientists monitoring the sun’s rapidly flagging behavior agree the growing likelihood of a grand minimum is stirring up a grand maximum of uncertainty and excitement. “We are not quite sure what the consequences of this will be,” says Yvonne Elsworth, a solar physicist at England’s University of Birmingham, “but it’s clear that we are in unusual times.”