‘Unbroken’ author on hope, horses and heroes

Laura Hillenbrand speaks to Fox News' James Rosen about her best-selling books 'Unbroken' and 'Seabiscuit'

I won’t kid you: When Laura Hillenbrand finally stepped into my frame of view, alighting at the bottom of a wooden staircase in her living room six feet away from me, the moment carried real drama for me.

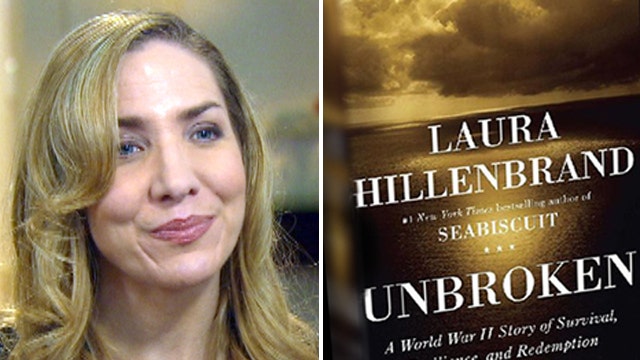

Why should it have? Standing before me was a slender, middle-aged blonde, attractive and well put-together but otherwise unremarkable-looking, clutching her iPhone and reading glasses in her left hand.

I can assure you the drama had little to do with the fact that the lady welcoming me into her elegant, newly-renovated Georgetown townhouse is one of the most successful nonfiction book authors in the history of American publishing, a writer in a class by herself, whose two books – "Seabiscuit" (2001) and "Unbroken" (2010) – have sold more than 10 million copies and both been made into first-rate, big-budget, Oscar-worthy films.

Rather, what had me paying such close attention in the moment was simply that it had been so long in coming. Four years earlier, when "Unbroken" had first appeared, Hillenbrand had promised Fox News an interview and I had been assigned to conduct it. Several times we finalized the scheduling, only to see Laura, close to the appointed hour, cancel – citing her longtime struggle with chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis.

After the fourth such cancellation, we decided to let Laura be, and carried on with an extraordinary interview, in California, with her riveting subject: Louie Zamperini, the 1936 Olympian, air crash survivor and heroic World War II P.O.W. whose singular story Hillenbrand relates, in harrowing detail and sparse prose, in "Unbroken." That story on Zamperini aired in December 2010 on “Special Report with Bret Baier.”

At the time, it had been a treat even to correspond with Hillenbrand, to glean from her emails a sense of the author’s goodness and polite self-consciousness, and even a sense of humor. But not landing the interview was a serious professional disappointment, exceeded only by the knowledge that a woman in the prime of her life – and at the pinnacle of her profession – was suffering terribly, closed off from the world and unable to reap fully the rewards her own hard work had engendered. Our houses at the time were all of six blocks from each other.

So when Hillenbrand, miraculously feeling worlds better, last month invited Fox News, and me, to her new digs in Georgetown to conduct The Interview That Never Was, this time to promote Angelina Jolie’s big-screen version of "Unbroken," I was excited not only to meet one of the country’s most brilliant and successful authors but also – there is no denying it – to lay eyes on the elusive, reclusive creature, to see for myself what kind of shape this Howard Hughes of American Letters was really in.

The camera men, producer and I could hear Laura’s laughing, seemingly carefree-sounding voice from upstairs as she finished last-minute preparations. With the click-clack of her heels on the hardwood steps heralding her imminent appearance before us, it was the holding of the iPhone and eyeglasses in one hand that struck me first: A person unsteady in her gait, concerned about vertigo – one of many symptoms Laura had recounted struggling with – wouldn’t, I thought, take the chance of allocating a hand to such possessions, would more likely keep them both free for the contingency of falling and needing to block her fall. It was encouraging.

Ultimately, we conducted a half-hour interview that covered three main areas: the writing of "Unbroken," the substance and lessons of Louie Zamperini’s amazing life story – he passed away in July, at the age of ninety-seven – and Hillenbrand’s thoughts on the movie. One question I asked was whether the task of researching "Unbroken," with its South Pacific locales, was harder than that which had informed "Seabiscuit." "It definitely was a more far-ranging hunt for the information about [Zamperini’s] life, but I got really lucky," Hillenbrand told me. "There was a lot to be found."

I found my respondent gracious, sharp, thoughtful and concise, not unpracticed at the business of being interviewed and given only to the merest hints of the kind of fragility one might expect of someone who has battled debilitating illness for so long.

She was, in a word, unbroken.