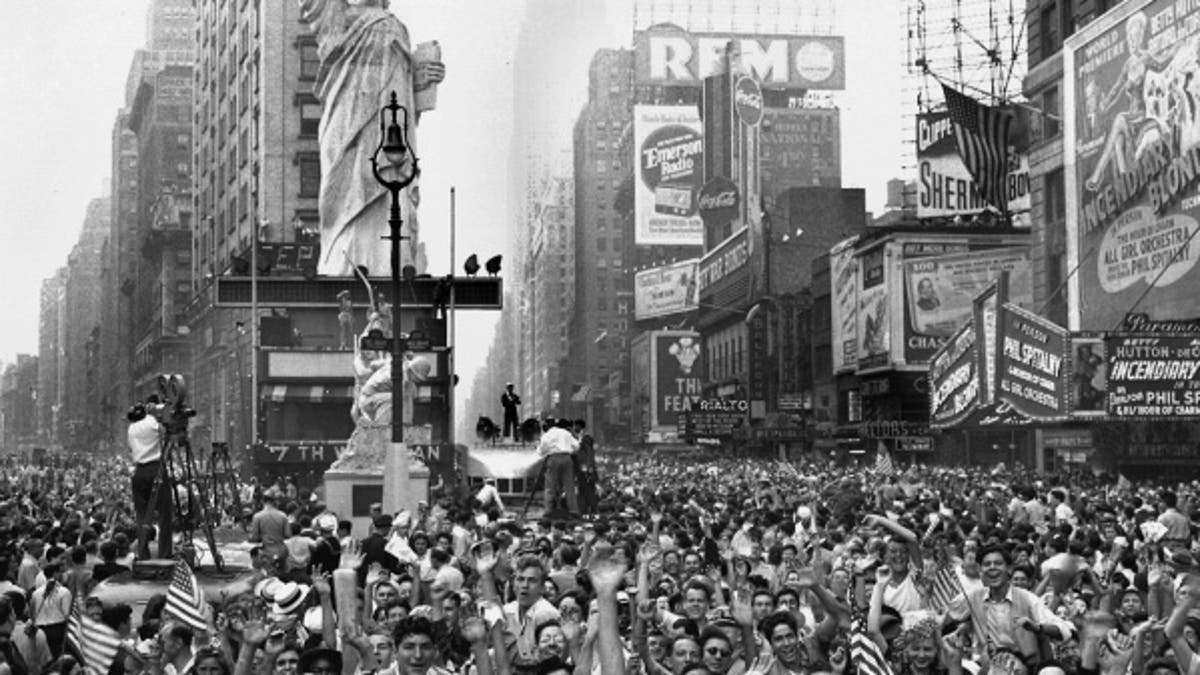

FILE -- Thousands of people celebrate VJ Day on New York's Times Square August 14, 1945 after Japanese radio reported acceptance of the Potsdam declaration. (AP Photo)

Sunday marks the 73rd anniversary of V-J Day – Victory over Japan, when World War II ended on Sept. 2, 1945 with Japan’s surrender to the United States in a ceremony about the battleship USS Missouri. It followed V-E Day – Victory in Europe – on May 8 that same year, when the Allies accepted the surrender of Nazi Germany.

If you’ve ever watched the classic film “It’s a Wonderful Life,” you may recognize these lines from the scene where an angel recounts George Bailey’s actions at the end of World War II: “Like everybody else, on V-E Day, he wept and prayed. On V-J Day, he wept and prayed again.”

When the movie was first released in 1946, audiences got the reference right away. They had just lived through that long and bloody clash of arms. They knew full well why people wept and prayed on the day when the war in Europe ended, and again when our hostilities with Japan came to a close.

But 73 years later, it’s a different story. At a time when many aren’t even sure what “V-E” and “V-J” stand for, their significance seems to have faded from memory.

Perhaps that’s because the images of a war’s end aren’t as stark as those that mark its beginning. Americans, after all, were jolted into the conflict by the horrific events and footage of Dec. 7, 1941, as Japanese fighter planes attacked U.S. ships docked at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

The scene on Sept. 2, 1945 was much quieter. And yet what was being communicated – that the United States would be magnanimous in victory and not pursue a vindictive peace – spoke volumes.

Such a stance is a proud fixture of American history.

Britain, the nation America fought in two bloody wars to win and then secure our independence, soon became our closest ally. Such healing also followed our nation’s Civil War, led by the stirring words President Lincoln delivered in his second Inaugural address.

Lincoln said: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

When the guns fell silent in 1945 it was the same story. U.S. Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur told those assembled on the deck of the battleship Missouri 73 years ago that they were not meeting “in a spirit of distrust, malice or hatred.” It was instead their duty to rise to a “higher dignity.”

“It is my earnest hope, and indeed the hope of all mankind,” MacArthur said, “that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past – a world founded upon faith and understanding, a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance and justice.”

It worked. Appealing to what President Lincoln once called “the better angels of our nature” led to a true and lasting peace. We didn’t put Japan under our thumb, creating rancor and vengeful feelings. We helped Japan rebuild and rejoin the nations of the world, not as a beaten foe but as a peaceful partner.

The result? More than seven decades later, Japan is one of our staunchest allies – one that helps preserve, rather than imperil, peace in the Pacific.

I see that as the true hallmark of American might. We use our power not for subjugation and conquest, but to stop aggression and right injustice. And once the battles have ceased, we work to lift up others and make the world a better, safer place.

The late Sen. John McCain, a man who lived true to the Warrior’s Code, embraced this conciliatory approach. Though tortured mercilessly as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam, McCain worked diligently not for revenge, but to normalize relations between the United States and his former captors.

As this true American hero explained in 2000: “The object of my relationship with Vietnam has been to heal the wounds that exist, particularly among our veterans, and to move forward with a positive relationship.”

An open-hands, open-hearts approach can work at home as well as abroad. In a time of rising incivility and escalating rhetoric, Americans would do well to follow Lincoln and MacArthur’s examples. To seek more peaceful ways to express our differences of opinion. Not to “repay evil with evil or insult with insult,” but to offer our blessings instead.

As the proud generations before us demonstrated, it’s never easy. But it very often is the right – and the smartest –thing to do.

And it’s what puts the “victory” in Victory Day.