Time's up for R. Kelly on Spotify

Top Talkers: The singer's music has been taken off playlists and recommendations after he was accused of sexual misconduct.

R&B artist R. Kelly, who has sold an estimated 60 million albums, has been indicted – but acquitted – of 21 counts of child pornography, accused of taking videos of himself committing sex acts with a 14-year-old girl. The charges against him allege conduct that any society would consider indecent and disgusting.

An exhaustive investigation by Chicago-based journalist Jim DeRogatis, who reported on the sex tape allegations in 2002, found credible allegations against Kelly of harboring underage girls against their will and using them for sexual acts. Early this year, a former partner of Kelly charged that he had purposely infected her with a sexually transmitted disease.

The Washington Post extensively detailed how music industry professionals surrounding Kelly simply turned the other cheek when reports alleging abuse by Kelly surfaced over several years.

The Time’s Up Women of Color – an anti-sexual harassment group headed up by actress Rashida Jones and film director Ava DuVernay – has called for boycotts of Kelly’s music and issued demands, in the face of the growing #MeToo movement, that his label drop him.

Kelly – though just one of many men accused of sexual misconduct caught in the #MeToo empowerment wave – is an especially disturbing case given the allegations against him, even though he was acquitted in a court of law.

But using the allegations against Kelly, and the momentum of the Time’s Up Movement, music streaming service Spotify is taking things a troubling step further. In an apparent detour from being a streaming service of music to cast itself as a socially conscious new media company, Spotify announced a new “Hate Content and Hateful Conduct” policy for artists featured or licensed with the service.

Spotify, which currently reports over 140 million active users, won’t disclose what this new policy specifically means. It declares on its website: “Spotify is a platform for artistic expression, exploration, and inspiration. We believe in openness, diversity, tolerance and respect, and we want to promote those values through music and the creative arts. This policy is designed to do that, consistent with our distinct roles in music and media – from distribution to promotion to co-creation. That’s why we do not permit hate content on Spotify, and remove it whenever we find it.”

Spotify is a streaming music service, so one can safely assume the company is referencing musicians, compositions, arrangements and songs. The company goes on to say it will be relying on three primary methods of monitoring “Hate Conduct” by artists on the service.

Spotify states: “Content monitoring: We are continuing to develop and implement content monitoring technology which identifies content on our service that has been flagged as hate content on specific international registers. Expert partners: We regularly consult with rights advocacy groups to review their most recent analyses of hateful content. Your Help: If you feel any content violates our hate content policy, complete the form here and we will carefully review it against our policy.”

Spotify, in the same statement also goes on to address “hateful conduct by an artist” stating: “What about hateful conduct by an artist? We don’t censor content because of an artist’s or creator’s behavior, but we want our editorial decisions – what we choose to program – to reflect our values. When an artist or creator does something that is especially harmful or hateful (for example, violence against children and sexual violence), it may affect the ways we work with or support that artist or creator.”

A closer look at who Spotify is relying on to police content – a group that includes the far left Southern Poverty Law Center – should worry users of the service.

If this sounds like a social justice mess Spotify is creating for itself, that’s because it is. At worst, it appears as though Spotify – as a company that prides itself on artistic musical expression from countless genres – is wading ever so slightly into censorship territory previously reserved for satanic panic witch hunts, like Tipper Gore’s Parents Music Resource Center.

Spotify has stated, in response to accusations against Kelly, however, that it will not remove his music from the streaming service. It simply won’t actively promote his music on playlists or generated content. Perhaps Spotify should make this easier and just declare which artists it finds non-offensive and universally agreeable. It will be a short playlist.

Spotify declares that content it deems hateful “expressly and principally promotes, advocates, or incites hatred or violence against a group or individual based on characteristics, including, race, religion, gender identity, sex, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, veteran status, or disability.”

Under every track on Spotify there is now a button where users can report such content they deem offensive or “hateful” (which I’ve personally done for Katy Perry’s entire catalog). So where to begin? Spotify can start by removing The Beastie Boys, The Doors, David Bowie, Prince, James Brown, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, The Sex Pistols, The Velvet Underground, Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash from its catalog, just to name a few.

Prince (Reuters)

Bob Dylan needs to go simply for the lyrics “she aches just like a woman but she breaks like a little girl.” Pete Townshend was cleared on child pornography charges in 2003. Spotify needs to remove The Who regardless, just to be safe. Is Spotify aware of where Joy Division got its name?

Bob Dylan (Reuters)

Prominent indie rock band The National arguably promotes rape culture in its hit song “Bloodbuzz Ohio,” when singer Matt Berninger drones: “Lay my head on the hood of your car, I’ll take it too far.” Lou Reed sang of wanting to be black, so he needs to be reported.

Ben Gibbard seems like a sweet unassuming songwriter for the band Death Cab for Cutie, but he doesn’t actually offer consent before saying he will follow you “Into the Dark.” Singer-songwriter Ryan Adams manterrupted Taylor Swift’s entire album “1989.”

John Lennon and Paul McCartney sang: “Well, I’d rather see you dead, little girl, than to be with another man. You better keep your head, little girl or you won’t know where I am” in the song “Run for Your Life” on the Rubber Soul album – so they’re reported. And don’t even get me started on the Beatles song “Getting Better.”

John Lennon and Paul McCartney (AP)

The line “Calm down, don't you resist” in the Foo Fighters’ “All My Life” seems super problematic on several levels.

Elton John, The Pet Shop Boys, Minor Threat, Guided By Voices, indie pop band Fiery Furnaces, Tears for Fears, Marilyn Manson, Tyler the Creator, Tori Amos and Dead Milkmen have used derogatory terminology in lyrics describing gay people. All reported.

Long time industrial rock band Nine Inch Nails – a band with a colorful history with lyrics – just released a new track this week. Did Spotify have the moral betters comb through writer/singer Trent Reznor’s lyrics before offering it on Spotify for fans to listen to?

This could go on forever. But instead of going down the line, artist by artist, Spotify could probably save everyone a lot of time and just shadowban everything convicted murderer Phil Spector produced.

Artist Chris Brown was a featured top artist on Spotify’s home browsing page. Brown has his own storied history with abuse toward women. And while the Brown example is an extreme point, I don’t think Spotify has taken the time to consider how embracing both the Southern Poverty Law Center and The Time’s Up Women of Color group and their standards of artist content and conduct will disproportionally affect black artists in hip-hop. Hard to fathom how our brave new tolerance patrol would be out promoting N.W.A. today.

Chris Brown (Reuters)

Woke media outlet The Verge declared in its headline: “Spotify’s new rules regarding hate content also apply to horrible human beings.” Well here’s a newsflash – many musicians are horrible human beings, because horrible human beings create some of the most artistic and impactful music.

This isn’t quite in line with demanding artists like Kanye West follow a certain thought pattern, but if Spotify and the Southern Poverty Law Center are going to start policing musician’s behavior and words, they are going to be very, very busy.

And stopping short of unsubscribing, you – the listener, the user and the subscriber – are powerless to stop any of this because Spotify owns the music, not you. Spotify’s power to influence artists in such ways comes from the power of distribution, and lack thereof.

Gone are the days when someone, curious about the moral scolding over Judas Priest, could walk into an underground record store to search out the group. Subscribers now become the willing participants in Spotify’s ridiculous thought policing, whether they agree with it or not.

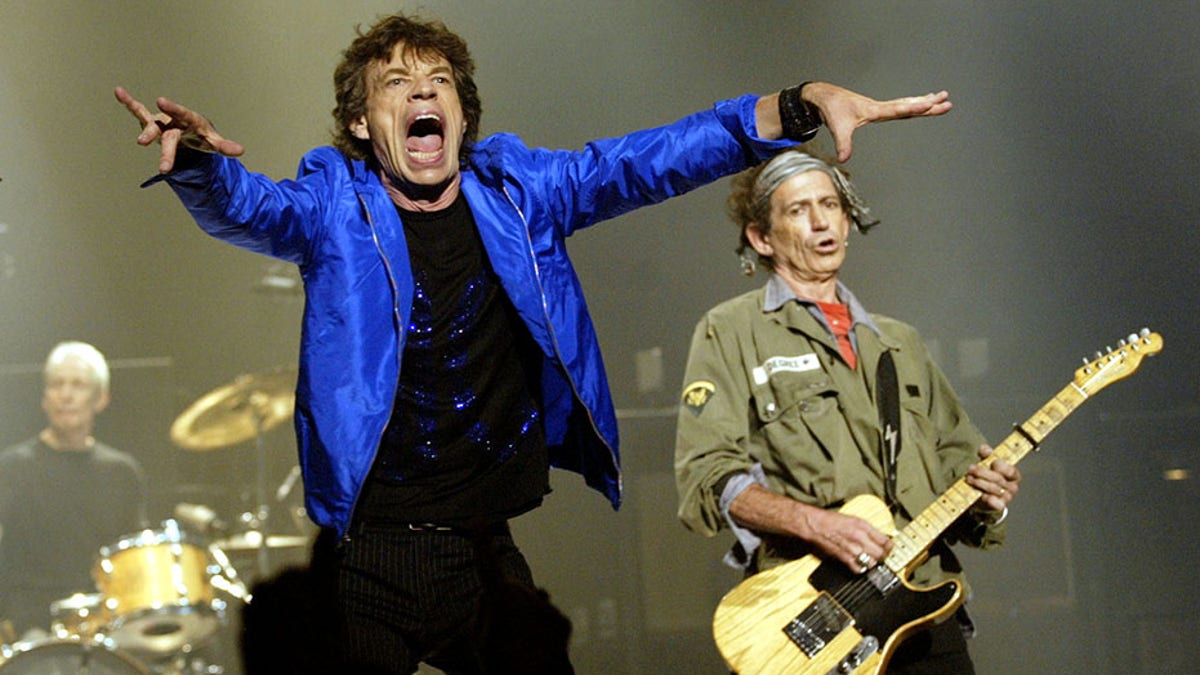

The Rolling Stones (Reuters)

This is the worst nightmare of an industry already rife with concerns about going almost fully streaming from vinyl, cassettes and CDs. This is the “filthy 15” on steroids and thankfully, even a little bit, some noted publications in the industry are taking notice of the dangerous precedent this could set.

As Billboard noted when Spotify made its announcement: “When it comes to hateful content, Spotify reserves the right to scrap music from the service: ‘When we are alerted to content that violates our policy,’ Spotify writes non-specifically, ‘we may remove it (in consultation with rights holders).’ Spotify already began this practice last August, when it outright removed a handful of white-supremacist and neo-Nazi acts that had been flagged by the Southern Poverty Law Center.”

This is a formula to kill artistic freedom – yes even by artists we may find deplorable, like R. Kelly or Kill, Baby, Kill. Every artist should take a step back at who Spotify is entrusting to carry out its new content policing.

Furthermore, modern artists should go to YouTube and dig up the footage of Frank Zappa and Dee Snyder testifying in front of Tipper Gore and the Parents Music Resource Center in 1985. If Spotify continues down this path, then artists need to realize they have the power to make Spotify suffer the same fate as the Tipper Gore group – an extinct laughingstock and stain on the history of free expression through music.