As lethal as modern warfare has become, it’s comforting to know that today’s soldiers stand a better chance than ever before of surviving combat injuries. In Afghanistan, battlefield first aid, rapid evacuations, and quickly reachable military field hospitals have saved thousands of men and women who might otherwise have died. What’s remarkable about these casualty management procedures is that they haven’t changed that much from the 1860s, when they were introduced in the Union Army.

Innovations in battlefield medical care came about in the early part of the Civil War in response to the horrendous conditions wounded soldiers faced. A classic example was the Battle of Second Manassas (Second Bull Run to the Confederates), a clash in late August 1862 in which Confederate troops defeated Union forces. More than 22,000 soldiers were killed or wounded in the Virginia conflict—nearly 14,000 of them Federal troops. Wounded soldiers were strewn about the battlefield, crying out for water and medical attention. Their shrieks and moans increased as the days wore on. A full week would pass before all of the Union injured were removed from the battlefield and transported to hospitals—grisly proof of the Army's appalling inefficiency in dealing with casualties.

Miraculously, the outlook for the wounded changed just two weeks later. On September 17, 1862, Union and Confederate forces clashed again at Sharpsburg, Maryland, in the Battle of Antietam. After 12 hours of fighting, some 23,000 men (over 12,000 Union soldiers and more than 10,000 Confederates) had fallen—the bloodiest single day of combat in American history. In stark contrast to the delays experienced at Manassas, every injured Union soldier was evacuated from the Antietam battlefield within 24 hours.

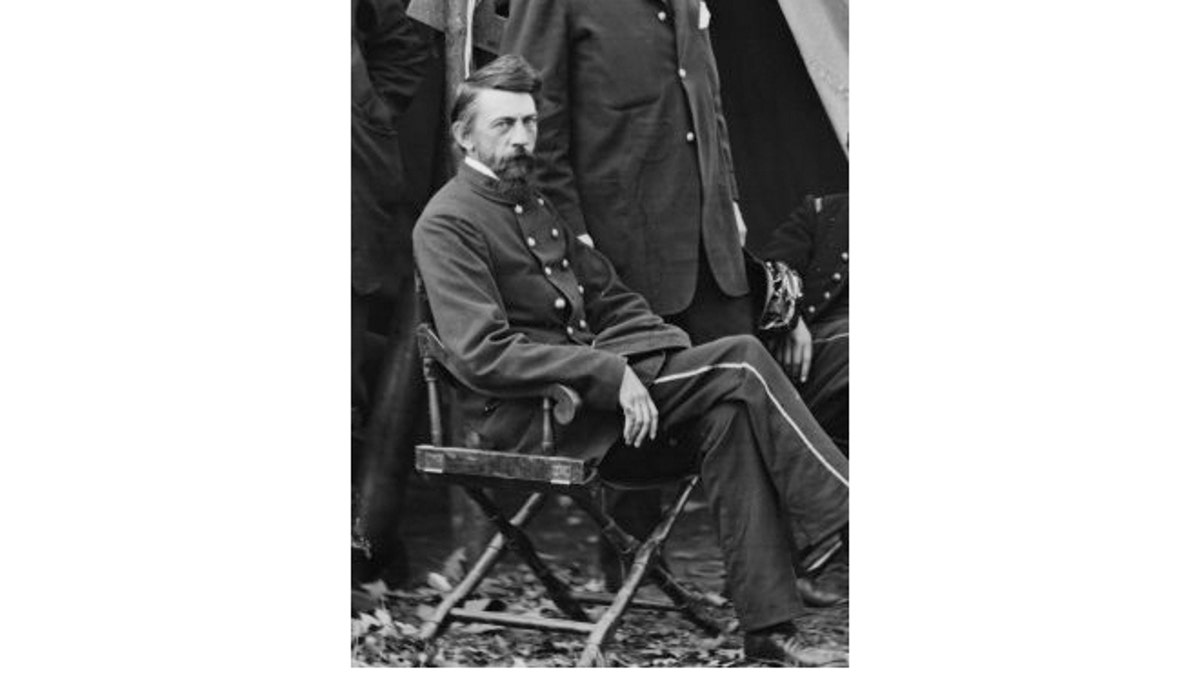

The author of this dramatic turnaround was a lanky, bearded, Donald Sutherland look-alike—Maj. Jonathan Letterman, a 37-year-old military surgeon who'd been named medical director of the Army of the Potomac three months earlier. Letterman's genius revealed itself the moment he took up his new duties. He immediately instituted revolutionary improvements in battlefield casualty management, and at Antietam, his reforms began to pay off. Letterman's innovations were so farsighted that they're still used today, earning him the title of the Father of Battlefield Medicine.

To speed the evacuation of wounded soldiers, Letterman created the Union Army's first ambulance corps. He set up a uniform system of first-aid stations and field hospitals that brought order to the formerly chaotic, inconsistent treatment of the wounded. He also made sure that medical units received the necessary equipment and supplies. And long before the triage system of medical evaluation was employed in World War I, Letterman instituted standards for prioritizing treatment based on the severity of injuries and the likelihood of survival. Thanks to his efforts, thousands of soldiers survived who might otherwise have died from their wounds.

Born in 1824, Letterman was the son of a prominent Pennsylvania surgeon. He grew up in the town of Canonsburg and graduated from the local Jefferson College in 1845. After graduating from Philadelphia's Jefferson Medical College four years later, he immediately applied for a commission as an Army surgeon. Stationed in California when the Civil War erupted, he returned east at the end of 1861. The following May, he became the medical director of the Department of West Virginia, followed quickly by his appointment as medical director of the Army of the Potomac. At the time, the Army of the Potomac was in a sorry state, with thousands of sick or wounded troops. Letterman recognized that many of the soldiers were suffering from scurvy, which he quickly cured with increased rations of fresh vegetables. Other problems weren't so easy to fix.

Letterman and his fellow Civil War doctors had to cope with a scale of battlefield casualties that no one could have anticipated. The Battle of Second Manassas alone produced twice as many casualties as the entire Revolutionary War. The shocking carnage resulted from a combination of improved weaponry and outdated military tactics. Generals on both sides still employed the mass charges of the Napoleonic era, yet in the face of newer weapons, that sort of head-on assault was suicidal. It was common for units to lose a third or more of their men in a frontal assault.

Over 90 percent of Civil War battle injuries came from gunshots, most of those from the ugly half-inch chunk of metal fired from the Springfield musket—the minié ball, a soft lead bullet that could shatter bones and punch a fist-size hole in a man. Two other brutally effective projectiles were canister shot and grape shot—cannon shells filled with dozens of small iron balls. When the shells were fired, their casings broke apart, spraying the iron balls into oncoming soldiers in a wall of death, like a giant sawed-off shotgun.

The extreme numbers and unusual severity of battlefield casualties taxed the woefully understaffed Army medical corps all through the war. In 1860, the U.S. Army had just over a hundred doctors to treat its 16,000 soldiers. Although the medical corps grew to more than 10,000 surgeons by the end of the war, the ratio of doctors to soldiers actually went down, since the Union Army had swollen to well over two million men by 1865. (Confederate doctors faced an even more daunting situation, with just 4,000 doctors to treat more than a million soldiers.)

Besides having too few doctors, the Army had to rely on physicians with rudimentary skills. Basic medical procedures hadn't changed much in generations. Doctors usually received only cursory training, often at unregulated two-year medical schools. Most new doctors had never dealt with gunshot wounds or performed surgery of any sort. Their real training came on the job—hacking on the unfortunate soldiers who ended up on their operating tables. Thankfully, chloroform had come into wide use a few years earlier, and morphine and opium were available to ease soldiers' pain.

Since most Civil War doctors weren't qualified to operate on serious wounds to the head, chest, or abdomen, those injuries were considered fatal and usually left untreated, other than to give the victim painkillers. The most frequent wounds by far were injuries to the extremities, making the amputation of limbs the most common surgical procedure. A practiced "sawbones" could remove a mangled arm or leg in ten minutes, using a variety of fearsome knives and saws.

In the heat of battle, the typical field hospital looked like a scene from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, with surgeons spattered in gore and body parts tossed onto grotesque piles. Surgeons toiled amid the screams of the wounded, the explosions of cannons and rattling of musket fire close at hand. Their bare arms glistened with sweat and blood as they bent over the operating table for hours on end.

Unaware of the relationship between bacteria and infections, Civil War doctors used the same surgical instruments over and over without bothering to sterilize them, leading to postoperative infections that included blood poisoning, tetanus, and gangrene. Despite the lack of surgical hygiene, nearly three out of four amputees survived, but there were still plenty of other ways to die. Of the 360,000 Union soldiers who died in the war, around 220,000 of them succumbed to illnesses such as chronic diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, pneumonia, tuberculosis, smallpox, malaria, and measles.

The deadly mix of injury and illness was exacerbated by the haphazard organization of the Army medical corps in the early part of the war. When Jonathan Letterman took over as medical director of the Army of the Potomac, medical personnel had no ambulances or dedicated stretcher-bearers. Even worse, there was no coordinated hierarchy for treating the wounded, and doctors ran out of critical supplies far too often. Letterman knew that the key to saving injured soldiers was getting them immediate help. His plan for the Army of the Potomac called for a fleet of wagons that would only be used for transporting the injured, and it required each regiment to assign stretcher-bearers who would have no combat duties.

Letterman organized the treatment of casualties into three stages: battlefield first-aid stations for stopgap measures, nearby mobile field hospitals for surgery and other emergency procedures, and more distant general hospitals for follow-up care. That simple three-tiered system remains the blueprint for modern battlefield medicine (the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital made famous in the 1970 movie MASH and the subsequent TV series was the ultimate expression of the Army field hospital of Letterman's day). Finally, Letterman organized a dependable system to provide surgeons with the medical equipment and supplies they needed.

Letterman's comprehensive revamping of the Army of the Potomac's medical corps continued to prove its value after the Battle of Antietam. The new system's biggest test came at the Battle of Gettysburg, which took place July 1-3, 1863, in southern Pennsylvania. The most famous battle of the war involved over 158,000 soldiers—some 83,000 Northern troops led by Gen. George G. Meade and 75,000 Rebels commanded by Gen. Robert E. Lee. The Union victory produced a staggering 51,000 casualties (23,000 Federals and 28,000 Confederates). Letterman's ambulance corps fielded 1,000 horse-drawn wagons manned by 3,000 drivers and stretcher-bearers. Remarkably, the medical workers were able to clear the wounded from the battlefield by July 4.

Six months after the Battle of Gettysburg, Letterman abruptly ended his association with the Army of the Potomac due to a political squabble. Fortunately for the common soldier, the changes that Letterman fostered were kept in place. In March 1864, the Army of the Potomac's model of casualty management was extended throughout the military.

In December 1864, Letterman resigned his Army commission and moved to San Francisco, where he practiced medicine and won election to the office of coroner. In 1866, he published his Civil War memoirs, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. Letterman died in March 1872 at the age of 48. In 1911, the Army hospital at San Francisco's Presidio was named in his honor. Letterman is now interred at Arlington National Cemetery. His headstone bears the following tribute: "Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, June 23, 1862, to December 30, 1863, who brought order and efficiency into the Medical Service and who was the originator of modern methods of medical organization in armies."

In human terms, Letterman did much more than what's indicated in that simple epitaph. He touched thousands of lives—from his own time right up to the present. Battlefields everywhere are emblazoned with memorials commemorating the deeds of fighting men, but few make note of the heroic accomplishments of those who struggle to save lives rather than take them. These healers of the fallen have always done the best they could to ease soldiers' suffering. And in that worthy endeavor, they had no greater ally than Jonathan Letterman.

Jonathan Letterman is one of thirty overlooked heroes in Paul Martin's latest book, "Secret Heroes: Everyday Americans Who Shaped Our World," published this spring by William Morrow.

Reprinted by arrangement with William Morrow.