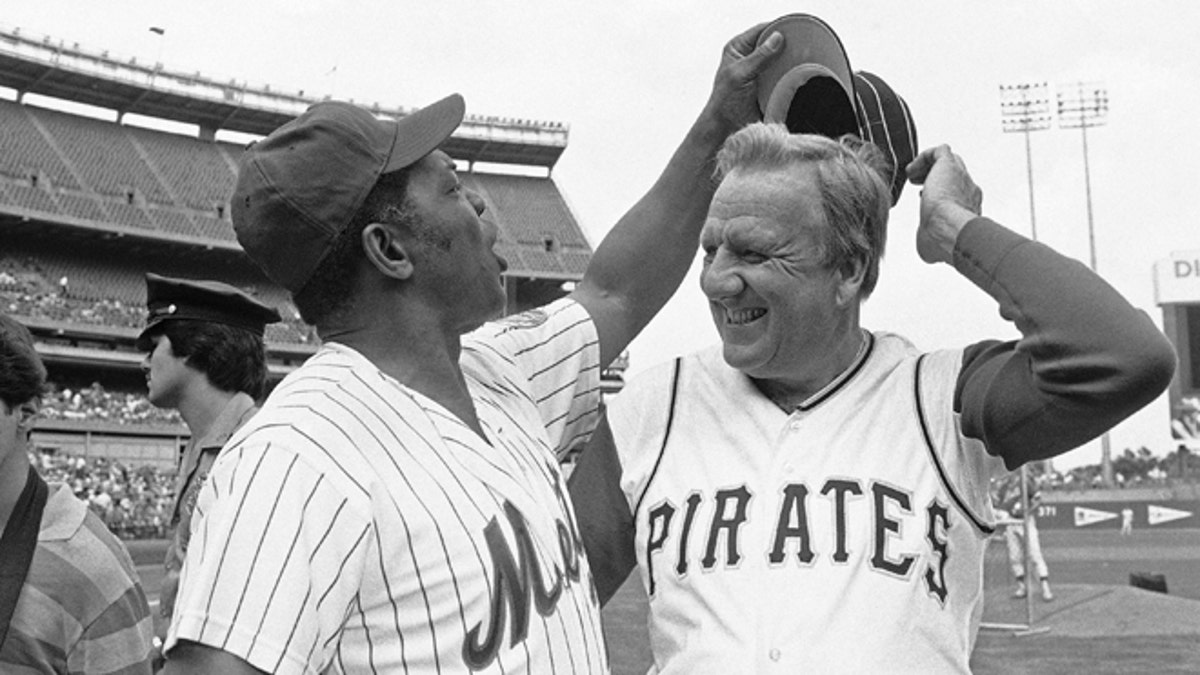

FILE - In this Aug. 14, 1982 file photo, Willie Mays tries to get Ralph Kiner's hat as the two Hall of Famers pose for pictures before the start of Old Timers Day game at Shea Stadium in New York. The baseball Hall of Fame slugger died on Feb. 6, 2014, at his home in Rancho Mirage, Calif. He was 91. (AP Photo/Harry Harris, File)

I will remember his cigars. When he invited me to be his guest after a Mets game to talk about baseball on his program, “Kiner’s Korner,” he inevitably was sporting a cigar.

He was always gracious and knew I shared his taste for a good Cuban, and so we would sit together, puffing happily, while the camera was off during commercials. And, like me, he loved to tell baseball stories, and he had some lovely ones.

I think some of his allure as a broadcaster was the store of good tales that he shared with his audience. Ralph Kiner’s death this week leaves me saddened. I will miss him.

[pullquote]

He was a star player when I was a kid and devoted fan during the ’50s, and I remember watching him on television as a stellar home run hitter at Pittsburgh.

He also drew attention because he obviously had a special attraction to and for lovely women, so I knew he had dated a full range of the Hollywood lovelies.

But he also was a student of hitting whose skills were heightened by his friendship with his teammate, Hank Greenberg. Ralph was enormously grateful to Hank for what his older teammate taught him. He sang the praises of Hank loudly and often.

When I took a lot of heat over the Pete Rose case, Kiner went out of his way to make clear his support for me. He never hesitated to voice opposition to the efforts Rose was making to gain admission to the Hall of Fame.

Kiner had no sympathy for Rose, and I was grateful to him for the clarity with which he addressed the issue. He and the iconic Bob Feller were among my closest supporters among the Hall of Fame idols. They never wavered.

But above all else, Ralph was a student of the art of hitting, and his devotion to that subject was intense.

At dinner one evening at Cooperstown during the Hall of Fame induction ceremonies, I was seated at one end of a long table with members of the Hall arrayed along both sides.

At the other end of the table, Ralph sat next to Johnny Mize, the superb first baseman for the Cardinals at his prime, though I recall him as a preeminent pinch-hitter for the Yankees at the end of his career.

Suddenly Kiner and Mize stood up, and I watched as Mize began to emulate his batting stance while obviously giving Kiner a batting lesson. These were gents well into their 70s at the time, and I was struck by what was obviously taking place. When the dinner ended, I asked Ralph what he and Mize had been doing.

“Well, Commissioner,” he explained,”I have always wanted to ask John how he was able to hit the inside fastball to the opposite field. He could take that inside pitch and hit it to left field, and I wanted him to show me how to do it.”

So here they were, two superb old-timers exchanging tips on how to hit when they both were headed only for the fields of dreams. It showed me the depths of their love for their art and the intensity they brought to their profession. To them the subject of hitting was a lifelong passion, and they could never stop studying it.

Kiner never formally retired from the Mets broadcast booth, and even last season he returned frequently. He never ran out of ways to explain what was taking place, and he usually was able to relate the action to some funny tale from his store of anecdotes.

Yet, for me, there was a serious undercurrent to Kiner’s love for our game. He could be funny, but he never treated baseball as anything other than a professional endeavor.

For Kiner, the game had to be played properly and with respect for both the traditions of the game and the rules. Fun could be had, and humor was present, but the game was about winning.

Even when Kiner got his tongue wrapped around his ear as he delivered some inane sentence, one could laugh with him. None of us ever laughed at him. We respected he was just being honest.

He never pretended to be more than he was. And for me he was one of a now smaller number of great former ballplayers whose love for the game was always bright and shiny. The cigar is out but the memories linger on.