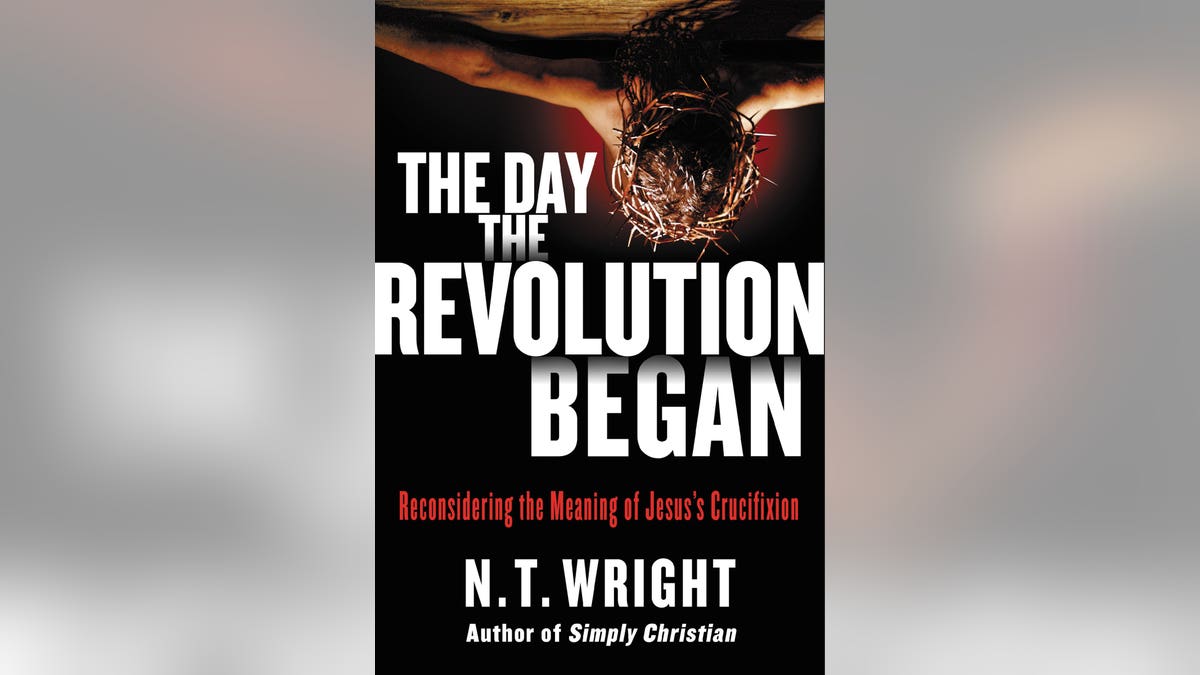

Christians forgotten 'revolutionary nature' of the cross?

Spirited Debate: N.T. Wright discusses why in his opinion that Jesus' crucifixion was a 'pivotal moment in history'

You can’t escape it. Whether it’s a tiny silver pendant or an enormous structure atop a hill (Rio de Janeiro, Montreal), the cross is both eye-catching and powerful.

So powerful, in fact, that a British airline worker was suspended for refusing to remove her cross in case it offended passengers.

TRUMP. OR NEVER TRUMP. WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU CAN'T AGREE WITH THE PEOPLE YOU LOVE

Millions with little connection to organized Christianity instinctively recognise the cross as iconic. The theater producer Peter Sellars, introducing his staged version of Bach’s "St Matthew Passion" in 2014, explained that in this story people of all sorts glimpse truth, and often comfort, beyond what is available elsewhere.

Why? Do we need to ask? You don’t need to know the science of cookery before enjoying a meal. Nor do you need to know music theory before you can be moved by Bach. But someone has to know how to cook; and the musicians need to know what they’re playing and how to play it. Those who teach in church, and those who commend the faith to outsiders, need to grapple with the meaning of Jesus’ death. Then the puzzles begin.

Some great mediaeval paintings of the crucifixion see Jesus as a battered, vulnerable man – with God the Father behind him, a stern, forbidding presence.

The message is clear. God is angry with us, but his anger is all poured out on the innocent Jesus. A caricature, of course, or worse.

The famous John 3:16 doesn’t say ‘God so hated the world that he killed his son’, but ‘God so loved the world that he gave his son’. But that easily gets twisted the wrong way round. Perhaps that’s because many angry despots, in public or domestic life, have beaten up innocent victims. Sometimes they even claim that they do it out of love. We have learned to shudder at such claims.

But isn’t that what the Bible says? ‘He was bruised for our transgressions . . . the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all’? Yes, but what matters is getting the story right.

Many Christians, whether Catholic or Protestant, liberal or conservative, have imagined a story like this. (1) We messed up badly; (2) God had to punish us; (3) fortunately, his innocent son got in the way and took the rap. But the Bible tells a bigger, more subtle story.

Paul’s summary of the Christian message begins, ‘The Messiah died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures’. That doesn’t mean “in accordance with the story we have in our heads, with a few biblical footnotes.” Paul is referring to the entire story of Israel’s ancient scriptures.

That story is not about ‘sin and what God does with it.’ It’s about creation and covenant.

First, creation: God made a wonderful creation, and put humans into it to sum up the praises of creation and to look after his world. This is what it means to be ‘in God’s image’: angled mirrors, reflecting God’s love into the world and reflecting creation’s worship back to God.

Some texts speak of this human vocation as ‘the royal priesthood’. When humans mess it up, it isn’t just that they break some arbitrary rule (‘don’t eat that apple!’). They are taking their orders from something within creation rather than from the creator himself. That is what the Bible calls ‘idolatry’. And it ruins creation as well as humans.

Here’s how it works: humans worship something other than the creator God, and so they think and act in less-than-fully-human ways, thereby failing to take forward God’s purposes for the world. That is ‘sin’: missing the target of true humanness.

The idols, meanwhile, gain power through our worship of them, and they use that to enslave us and corrupt the world.

Think of the contemporary idols: money, sex or power. We worship these forces, and they tell us what to do. So we shrink as humans; not just because we break various commandments (though we do) but because we miss our true calling, and the world suffers in consequence. And if we try to grab that vocation back again – if we try to run the world our way – our sub-humanness shows up all too clearly. Every tyrant, every anarchist, started off by thinking they knew how the world ought to be.

That’s why, when the New Testament talks of Jesus’ death and what it accomplished, it doesn’t just talk about dealing with sin (though it does that too). It talks about God overthrowing the dark powers that have taken over the world.

‘Now,’ said Jesus, ‘the ruler of this world is cast out.’

‘On the cross,’ wrote Paul, ‘Jesus disarmed the principalities and powers.’ That is basic. All the early Christian teachers knew this. That was why they lived as a multi-ethnic, classless community. The ‘powers’ that had kept humans locked up in their sins and their distinct social groupings had been overthrown.

The four Gospels explain the ‘how’. Jesus announced that God was becoming ‘king’, ruling the world as he always intended. This took Jesus to the cross, with ‘King of the Jews’ over his head.

Throughout the story, Jesus is opposed by forces of evil, human and non-human. The lies, hatred and evil of all the world rushes together in one place and nails him to the cross.

When he rose again three days later, his followers realised that this could only be because, on the cross, he had exhausted sin’s power. He had taken on himself the punishment of ‘sin’, so that the grip of the ‘powers’ would be broken. New creation was now launched as a result – with rescued humans at last reflecting God’s purposes into that new world.

What does this mean today? Not just that believers have fellowship with God, now and hereafter, though it does mean that, too.

It means that the door of our prison stands open and we are free to resume our vocation. To be image-bearers. To be the ‘royal priesthood’. To worship the living God freely. To be his agents in the world – not by the world’s normal bullying methods, but by following the royal way of Jesus.

It’s all there in the Sermon on the Mount: blessed are the peacemakers, the hungry-for-justice people, those who care for the poor, who live without anger or lust: those who make the world a radically better place.

That has been going on for two thousand years, though we often forget it. It stands at the root of our somewhat battered concept of ‘human rights’. That wasn’t invented by secular modernity. It comes from Jesus – from Jesus as the focal point of the ancient vision of Israel, of covenant renewed and creation restored. From his victory on the cross.

That’s what it means when people place a cross around their neck, or on top of a hill.

It means that the power of love has overcome the love of power. And that it always will.