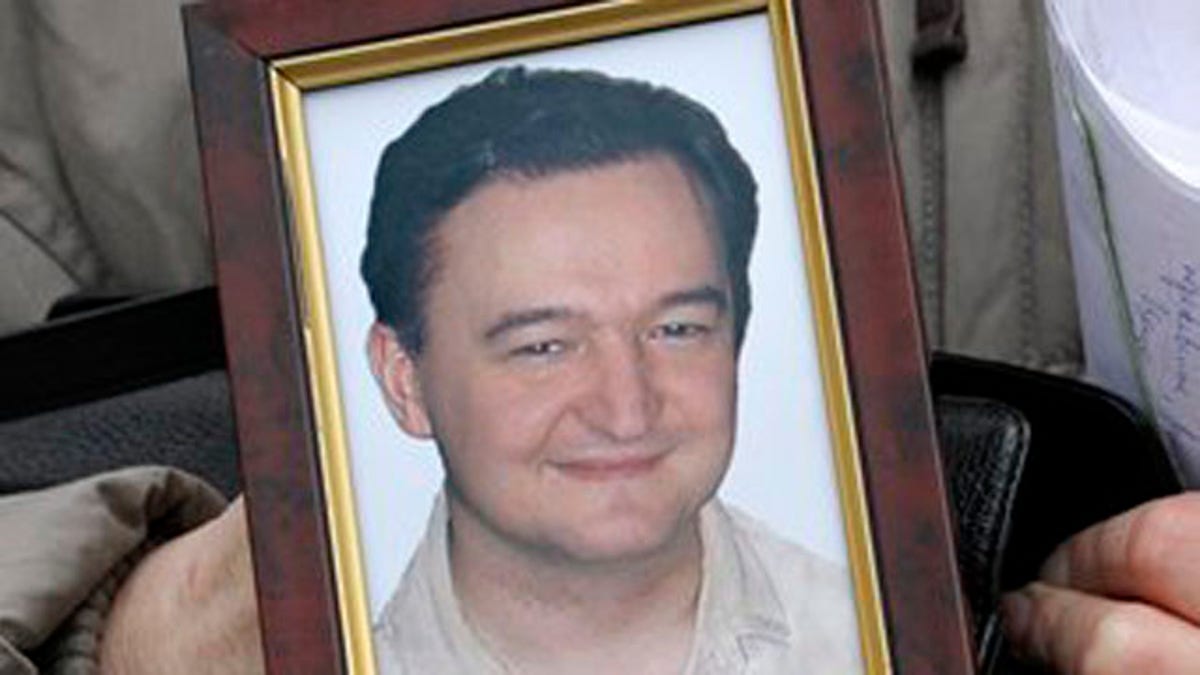

This is a Monday, Nov. 30, 2009 file photo showing a portrait of lawyer Sergei Magnitsky who died in jail, as it is held by his mother Nataliya Magnitskaya, as she speaks during an exclusive interview with the AP in Moscow, Russia, Monday, Nov. 30, 2009. (AP)

Tzvetan Vassilev, a fugitive indicted Bulgarian businessman, has hired a Washington law firm to help him avoid prosecution and settle a score with a politician by invoking the Magnitsky Act, a law that empowers the U.S. government to impose sanctions as retaliation for corruption and abuses of human rights.

The law was not intended to serve as a shield for those who allegedly committed financial crimes and then seek to cloak themselves in righteousness. As our own State Department has acknowledged, the law’s purpose is to “identify and hold accountable persons responsible for gross violations of human rights and acts of significant corruption.”

Clearly, the Magnitsky Act is not about creating an international get-out-of-jail-free card for fugitives like Vassilev.

The Magnitsky Act is named after Sergei Magnitsky, a Russian lawyer who discovered a multimillion-dollar fraud scheme among Russian tax officials. Magnitsky was arrested and held without trial. In 2009, seven days before Russian law required that he be released, he was beaten to death, becoming a worldwide symbol of repression in Vladimir Putin’s Russia and a martyr for freedom.

In the aftermath of Magnitsky’s death, President Obama and Congress worked together to enact the Magnitsky Act in 2012. The law was designed to punish the Russians responsible for Magnitsky’s death by barring them from entering the U.S. and from using the American banking system.

At the outset, the law blocked 18 Russian government officials and businessmen from entering the United States. The law was expanded last year to enhance the president’s power to sanction individuals outside of Russia and given global effect. It was then renamed the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act.

Already, 44 human rights violators, ranging from Russian district court judges to senior investigators for the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, have been put on the sanctions list, and are now barred from entering the U.S., and utilizing U.S. banks.

To be clear, Tzvetan Vassilev is no Sergei Magnitsky. As Reuters reported, Bulgarian authorities recently indicted Vassilev and others on charges of embezzlement and money laundering related to the failure of Bulgaria’s fourth-largest bank, Corporate Commercial Bank – in which Vassilev was the main shareholder.

All told, more than $1.5 billion was purportedly taken from the bank and pocketed by Vassilev and his cronies. For the record, it is one of the largest fraud investigations in Bulgaria since the fall of the Soviet Union.

As the prosecutor put it: “In essence the Corpbank model ... is a mechanism through which a group of people led by Tzvetan Vassilev managed to appropriate the public funds attracted and entrusted to them for management in the bank.” According to a 2014 audit conducted by Ernst & Young Audit, Deloitte Bulgaria and AFA, the bank’s loans had defied standard banking practices and responsible risk assessment. Only 13 percent of the loans on the bank’s books were actually backed by sufficient collateral. The other 87 percent were ticking financial time-bombs.

Not surprisingly, Vassilev has denied culpability and has fought extradition from Serbia, claiming that he is being wrongly accused.

Instead, Vassilev has pointed a finger at Deylan Peevski, a Bulgarian media owner, and Sotir Tsatsarov, Bulgaria’s chief prosecutor. Vassilev is asking the U.S. government to place economic sanctions on these two men using the new Magnitsky Act. Both deny his claims.

Looking at the bigger picture, Bulgaria is a member of both NATO and the European Union. In fact, this past summer, NATO conducted its military drills on Bulgarian soil.

As one U.S. district court observed about Bulgaria and its judicial system, to gain admission to the European Union, Bulgaria was required to demonstrate that it possessed a stable judicial system that adhered to the “rule of law.” The court also noted that Bulgaria was a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights.

Suffice to say, Bulgaria is not Russia, Iran, North Korea, or Libya – enemies and adversaries that have been sanctioned by our government, with systems rife with corruption.

Under these circumstances, the U.S. government and members of Congress should carefully scrutinize Vassilev’s application under the Magnitsky Act. Imposing sanctions here appears groundless. It would make a mockery of the letter and spirit of the law, and be an insult to the legacy of Sergei Magnitsky. We can and should do better than that.