On the 30th anniversary of the Los Angeles riots that shook America in 1992, we asked Triawna Wood, a lifelong Los Angeles resident, for her thoughts and insights.

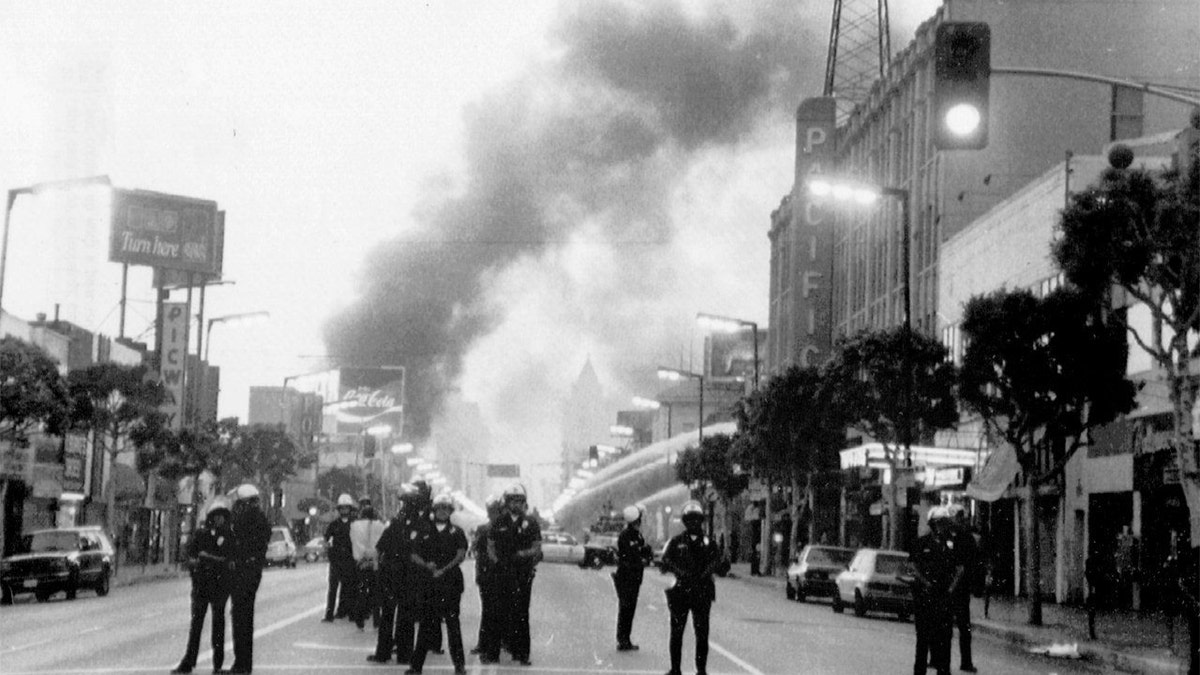

Los Angeles erupted after the Simi Valley jury acquitted Officers Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno for the beating of Rodney King. The riots lasted six days and when the smoke cleared, 63 people were killed, 2,383 were injured and more than 12,000 were arrested. The property damage was estimated to be well over $1 billion.

Wood was four and a half years old and living with her family in the Jordan Downs projects in the Watts neighborhood when the riots erupted. Today, she is a married Army veteran who homeschools her three children.

What follows is a Q&A that has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. We strongly encourage you to watch the accompanying video so you may hear Wood in her own words.

Q: Where were you when the Los Angeles riots began?

A: I was in preschool. My mom picked me up from school, we were coming back home. My normal routine was my mom would watch soap operas and once the soap operas went off, I knew that was my time to watch cartoons. But the soap operas got interrupted by the verdict. And I'm like, "How long is this going to last? I want to see my shows."

I remember my brother and sister coming home, my dad coming home, and then I guess hours later, you just started hearing noises outside. People were just outside, more than normal because it was usually pretty quiet. At this time we were living in the back, the very far back of the Jordan Downs projects, right before you got to Alameda. If there was like an earthquake, or random gunshots on a normal day, we would always go to the stairwell in the middle of the house, for safety, for shelter. I remember, specifically that night, spending that entire night curled up in my dad's lap on the upper part of the stairs, in the stairwell. The whole night, I fell asleep in his lap.

I'VE LIVED IN LA MORE THAN 30 YEARS AND I DON'T FEEL SAFE ANYMORE

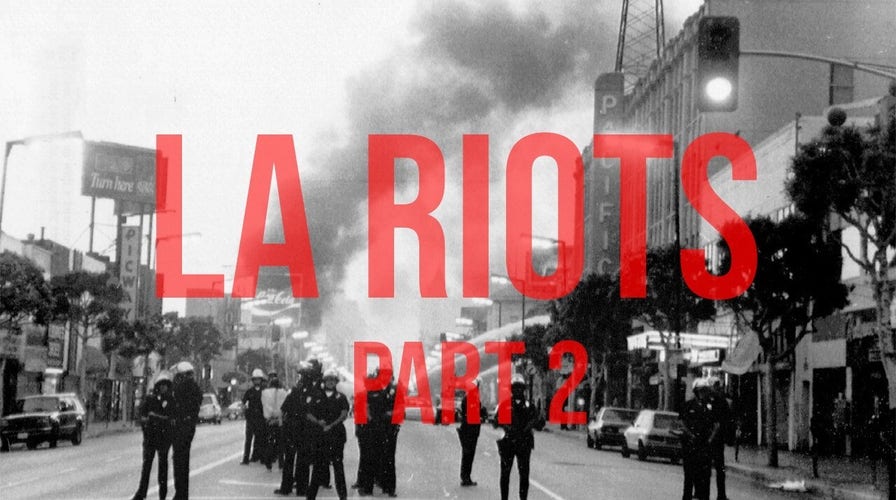

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA - MAY 1: Police guard Hollywood Boulevard after the Rodney King incident sparked riots. Photographed May 1, 1992 in Los Angeles, CA. (Photo by Dayna Smith/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

And then so the next day, my parents tried to tell us about what was going on. My brother and sister were old enough to understand more than I was. And they explained to me like, "You're not going to school the rest of the week—at least, until they tell us when you can come back." I was like, "Okay." So, we just pretty much hunkered down for most of the week.

Throughout the week, I remember my mom's friend bringing us groceries because she didn't live in the city. Because we couldn't come up here to this part of the neighborhood to go to the store, because this was the only grocery store in the area.

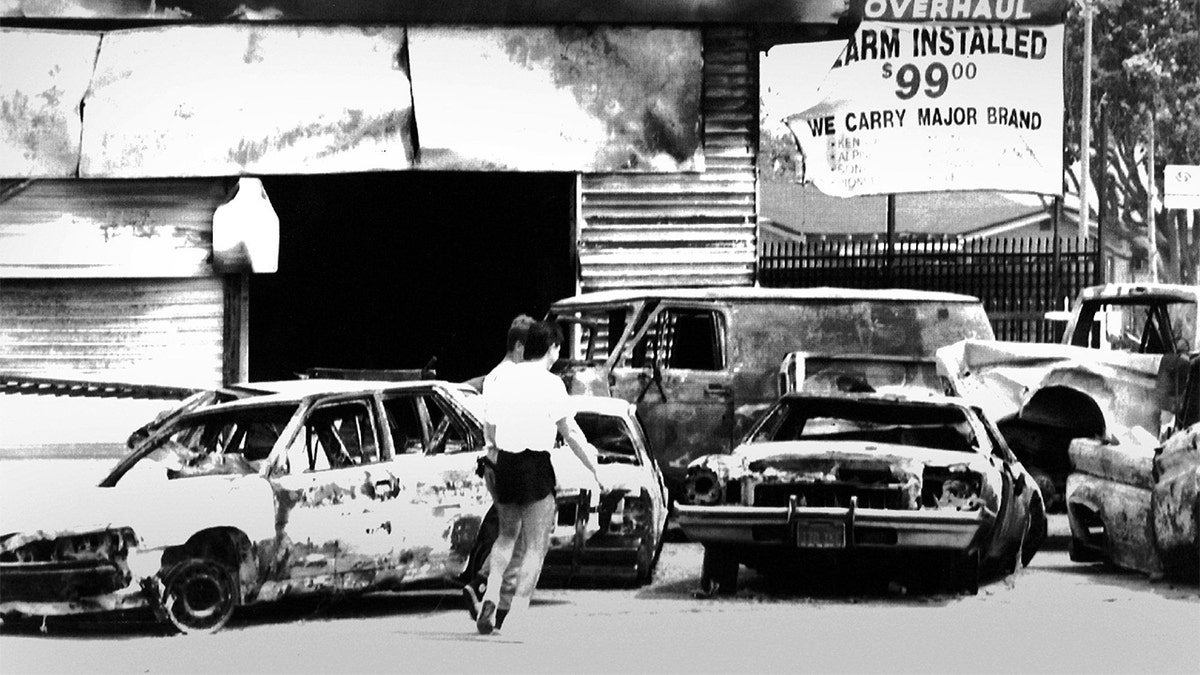

I remember the aftermath, the fallout later. After reemerging back into the world and looking at all the mom and pop shops, the liquor stores just boarded up or torn apart. And I remember thinking, as a little tiny four- or five-year-old, what do you make of this?

Q: What was the most vivid memory that you had?

A: The most vivid memory was learning that my family members, or people who were close to our family, weren't as savory of characters as I thought they were. I think that was the first time, specifically, a close relative of ours, I saw him in a different light. It was a person that I always thought was very protective, nice, funny. I didn't realize that this person was also into gang activity and took advantage of a time that was so violent, really. I think that was the first time that I saw him like that.

He wasn't mean when he came by our house or anything like that, but for him to offer ill-gotten goods, we were kind of like the black Brady Bunch. We were the wholesome family — in church every day, every week, year round. But that was the first time I had that interaction and was like, "Oh, we do know people that's like the bad people you see on TV." And that gave me a sense of the world is bigger than what I was aware of.

Q: Did you understand the anger of the rioters or were you more concerned with upholding law and order?

A: I remember my dad sitting down, explaining to me through his own stories of police harassment. And I started to understand like, "Okay, I know now that some people are going to treat me differently, because of how I look."

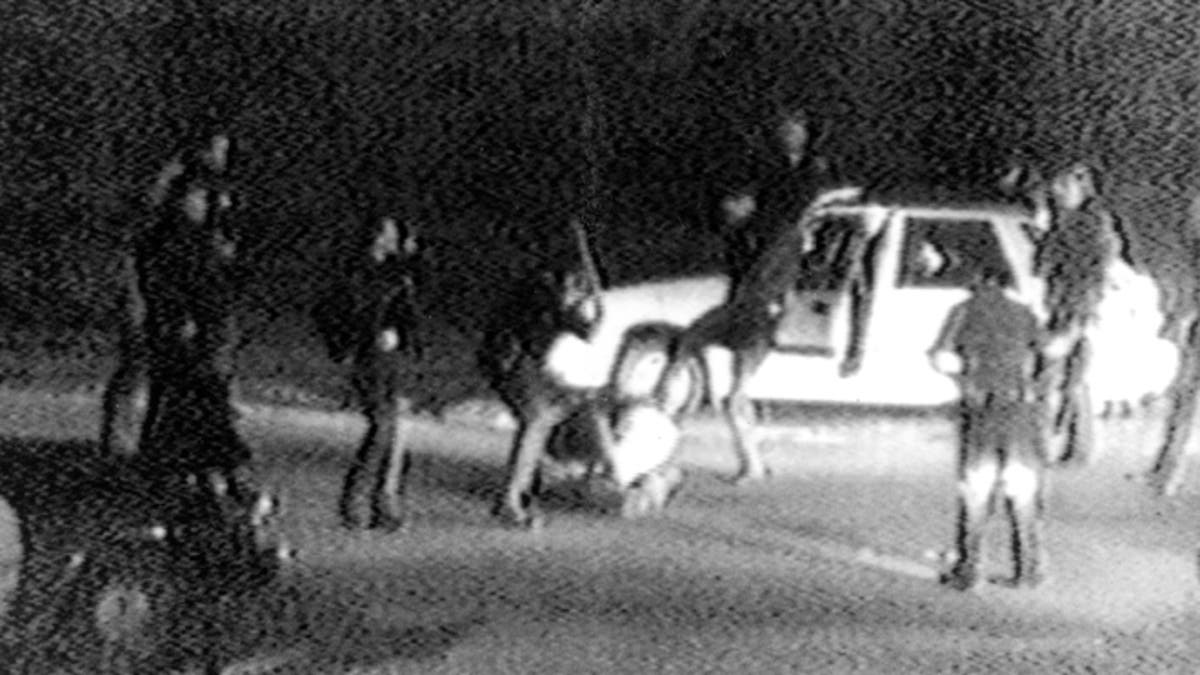

But, at the same time, I remember playing through my head, because I'd seen news clips of the Rodney King video, and I'm like, "Well, but if he was doing something bad, aren't they supposed to beat him up and arrest him?" But I didn't know that there should have been limits then. And so just putting all the puzzle pieces together as a young kid is like, "Oh. So, you don't just beat somebody bloody and then arrest them." But that's what I thought because that's what you see on TV, but you didn't expect to see it for real in life. And that was the first time that I realized, art imitates life.

March 31, 1991: FILE - This image made from video shot by George Holliday shows police officers beating a man, later identified as Rodney King. (AP/Courtesy of KTLA Los Angeles)

Q: What do you think is the biggest lesson to be learned from the riots?

A: One thing I think people did take from it is: maybe we shouldn't destroy our own stuff. But I don't think that should have been the only thing that people should have took from it. I think that if we learn to look at things as not just black and white, but more nuanced on an individual basis and pause before we react, maybe we can think of a stronger way to react that has a better impact for a better outcome.

Q: Do you think the rioting sent a message or do you think it hurt the black community?

A: I think it hurt more. But I think it also came out of hurt. It just became this vicious revolving door of just pain on top of pain. Because of not knowing how to process that pain in a healthy way.

Q: Has the LAPD improved in the years since the riots?

A: To be honest, they said that they were making improvements. I've met with a few officers and chiefs over the years for various different reasons. Some of them, their hearts seem like it's in the right place. But I don't think that they've had maybe enough opportunities to really engage in the change, in the process of actually becoming better. And I think that's because, one, the community has no trust. And two, a lot of younger officers … that started to replace the ones that were retiring, had no interest in the community that they're serving. And I think if there is improvement to be made, that's where it starts — in forging a relationship with the people of the community.

One thing I learned from being in the service, when I was in the Army before I was supposed to go to Afghanistan, you’d have months on top of months of training. You're learning the language, you're learning about the people, you're learning about their customs. What's considered okay, what's not okay. How to behave, how to talk to people, how to shake hands. Before you even set foot on the plane, you need to understand all of these things. And I think the police could take a chapter out of that book. How can you protect and serve a group of people that you really don't understand at all?

Q: The Los Angeles riots changed Los Angeles forever. How did it change the city? How did it change you?

A: It was one of many experiences or events in my life that was another drop in the bucket that basically solidified an idea in my head that I live in a country that never really cared about people who look like me. And that's hard to sit with, and I felt that pain and that anger for years, before I was able to even really process it.

But as far as changing the city? Yeah, I think it changed the city a lot. Especially the black community because it's living through a trauma that never gets acknowledged, never is openly talked about. So there's never room to heal from it, but that's the black experience throughout American history.

LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA - MAY 1: Burned-out cars at the intersection of Normandie and Florence in South Central Los Angeles after the Rodney King riots. Photographed May 1, 1992 in Los Angeles, CA. (Photo by /The Washington Post via Getty Images)

But as far as the city at-large, I think it's changed how we provide security. Like the shopping center around here, back then there were no gates around it. There wasn't a time of night where everything just closed up, and there was no way in or out. And there's so many places like that. There's so many extra security measures, and I don't know if I necessarily feel safer because of that. And I think people take for granted the freedoms that we had in exchange for a false sense of security …

People were much more closed off after that. I think that's when I started to see the shift in people not getting to know their neighbors. Even growing up in the projects, even though my parents were strict, I wasn't allowed to just hang out and go and do whatever, but we knew the majority of our neighbors for rows and rows. Everybody knew each other because it was a community. I think after that, you started to see a decline in that sense of community. People stopped talking to each other for various reasons, but on a larger scale.

Q: It never recovered?

A: Never recovered. Even in the neighborhood I live in now, when we first moved there, I said hi to introduce myself. And people just looked at me like, "The f***?" Like, "Who are you?" And I'm like, "Just saying hi, we just moved in." People think that it's normal, but that's not what I grew up with.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Q: You talked about how you felt anger. Were you able to work through it or are you still working through it?

A: I didn't know that my dad had run-ins with the police before. I didn't know that was a reoccurring thing. And I didn't know that I would eventually experience similar things. Even on a milder scale, but still. And it was just kind of like, what do you do with that? So as a teenager—yeah, the angsty teen. But as a black teen, you're not allowed to express that because now you're a threat. So, it took me years to just work on me and realize that no matter what has happened in the world, what has happened throughout history, that does not dictate where I want to be and how I want to be. And it took me years to work through that, to process all of those emotions, how I viewed the world. It even took me a lot of changing my own perspective, time and time again. I actively sought to get out, to explore, because this couldn't be the only way of looking at life.

I think if there's anything to probably leave off with, it's that we all suffer some type of trauma or pain collectively. It's not just individually, and it's not just subjugated to the minority communities. It's always another perspective that's happening at the same time. And I think if we focus on learning to see how others perceive that same event or series of events and realize that we all suffered some type of trauma from it, we can connect on a deeper level of understanding, how it affected the individual and how it affected us at-large as a society. I think when you have shared pain, it makes you stronger. It makes it easier to bond. But we have to get out of our own individual pain first in order to experience that type of bond.