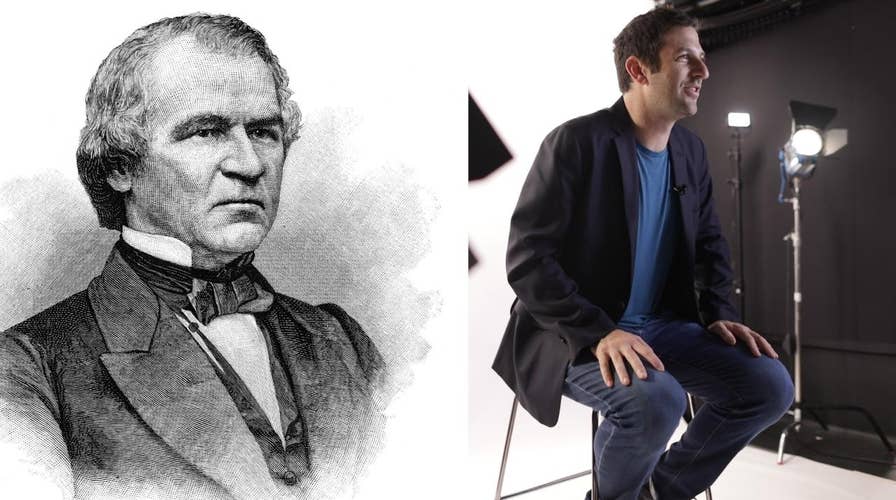

Jared Cohen: How a drunk vice president foreshadowed segregation

Jared Cohen explains the extraordinary scene that occurred when Andrew Johnson – sick with typhoid and three brandy glasses deep – was sworn into office as vice president on Inauguration Day, March 4, 1865. This was a day that foreshadowed segregation in a post-Civil War America.

Inauguration day, March 4, 1865, was a miserable day, but nonetheless an extraordinary scene. Abraham Lincoln had won re-election and the Civil War was all but won. His second inaugural address would later be regarded as one of the great speeches of his career, but not before his soon-to-be vice president made a drunken fool of himself.

Proceeding Lincoln, a red-faced Andrew Johnson – sick with typhoid and three brandy glasses deep – entered the Senate chamber around noon, arm in arm with Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, moments away from the most disgraceful and humiliating start to a vice presidency in American history. He ambled to his seat on the dais with the presiding officer, while Hamlin introduced the vice-president-elect – whom he didn’t much like – in a short 250-word speech.

After expressing his gratitude to his colleagues for their kindness during his tenure as vice president, Hamlin suppressed whatever bitterness he felt about having been tossed off the ticket and asked: “Is the vice-president elect now ready to subscribe the oath of office?” The combination of Hamlin’s introduction and Johnson’s speech was supposed to be a matter of minutes; instead, it turned into a 20-minute spectacle.

ACCIDENTAL PRESIDENTS, PART 6: CABINET CATASTROPHE AND A PRESIDENT IN LOVE

Andrew Johnson sauntered to the podium, where he began to speak extemporaneously in what seemed like an endless diatribe fueled by drunken bitterness toward everyone. The unusually high temperature in the Senate chamber certainly did little to counter the effects of alcohol flowing to his brain. Fortunately for Johnson, the combination of slurred speech and rustling in the visitors’ gallery made it almost impossible to understand what he was saying.

At perhaps the most important moment in his career, Johnson was overcome with hubris, condescendingly admonishing all who sat before him as not having earned their place through the same hard work that allowed him to ascend. His speech was absurd, declaring that all who stood before him owed their positions to the people. He then turned to publicly shame each member of Lincoln’s cabinet: “I will say to you, Mr. Secretary Seward, and to you, Mr. Secretary Stanton, and to you, Mr. Secretary . . .” At this point, Johnson embarrassingly forgot the name of the secretary of the Navy, paused his speech, and whispered to his friend John Forney, “Who is the Secretary of the Navy?” After being told the name, he continued his harangue, “and to you, Mr. Secretary Welles, I would say, you all derive your power from the people, whose creatures you are!”

Hamlin had seen enough and after 17 excruciating minutes pulled on Johnson’s coattails as both a nudge and gesture for him to stop. Johnson eventually took a moment to pause – presumably to breathe in between tirades – at which point Hamlin hastily administered the oath. Predictably, the oath of office, too, was a disaster. Johnson slapped his hand on the Bible, forcefully held the book up, and proclaimed in the sloppiest of voices, “I kiss this Book in the face of my nation of the United States.” And kiss the book he did. According to Benjamin Butler, the Massachusetts senator who would later lead the impeachment effort against Johnson, he “slobbered the Holy book with a drunken kiss.”

The spectacle wasn’t yet finished. Following the vice presidential oath, it had been tradition for the new vice president to swear in the new senators. Johnson tried to fulfill this duty, but by this time had become so disoriented that he handed the responsibility over to Forney, muttering to the surprised Senate clerk, “Here, you swear them in. You know it better than I do.”

The crowd was aghast, particularly as very few of them knew that Johnson had been sick or how much alcohol he had consumed. Beginning with the cabinet, Attorney General James Speed “sat with his eyes closed,” turned to his right, and whispered to Gideon Welles, “All this is in wretched bad taste. That man is certainly deranged.” Welles, still recovering from Johnson forgetting his name, conveyed his displeasure to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, whispering, “That man is either drunk or crazy.” Stanton, who himself “appeared to be a petrified man,” agreed “there is evidently something wrong.” Postmaster General William Dennison “was red and white by turns.” On the other hand, Secretary of State William Seward “was as bland and serene as a summer day,” later coming to Johnson’s aid by suggesting that his behavior was triggered by what must have been overwhelming “emotion on returning and revisiting the Senate.”

Lincoln, like everyone else, was visibly displeased. He closed his eyes and painstakingly averted his eyes from the humiliating spectacle. Senator John Henderson of Missouri, a close friend of Lincoln’s and co-author of the 13th Amendment, observed that the president, awaiting his own inauguration, sat with his “head dropped in the deepest humiliation,” not so much for himself, but on behalf of a man who appeared to be destroying a life’s reputation in less than 20 minutes. After recovering from the initial shock of the moment, he bent over and whispered to Henderson, also acting as a marshal for the inauguration, “Do not let Johnson speak outside.”

As the inaugural party moved from the Senate chamber to the steps of the Capitol’s east portico, it was as if the dark clouds that greeted Andrew Johnson dissipated just in time to inaugurate Abraham Lincoln. The president, with his inebriated vice president by his side, looked for any opportunity to ease the discomfort he had just witnessed. He noticed Frederick Douglass, the famous former slave whom Lincoln called a friend, standing in the crowd next to Mrs. Thomas Dorsey, the wife of another well-known ex-slave.

Douglass had been a frequent visitor to the White House and Lincoln proudly pointed him out to Johnson. What happened next is subject to interpretation. As Douglass would later recall in his autobiography, “The first expression which came to [Johnson’s] face, and which I think was the true index of his heart, was one of bitter contempt and aversion. Seeing that I observed him, he tried to assume a more-friendly appearance; but it was too late; it was useless to close the door when all within had been seen. His first glance was the frown of the man, the second was the bland and sickly smile of the demagogue.” He would describe this exchange of looks as one of those “moments in the lives of most men, when the doors of their souls are open, and unconsciously to themselves, their true characters may be ready by the observant eye.” Douglass had drawn his conclusion. Turning to Mrs. Dorsey, he said, “Whatever Andrew Johnson may be, he certainly is no friend of our race.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Perhaps this was the real Andrew Johnson’s unveiling, showing himself as a former master unable to conceal his disdain for the former slave. It is also possible that Johnson was just drunk, his surroundings spinning, his nausea kicking in, and his mind not entirely present. Anyone who has ever had too much to drink can imagine how a drunken glance could be mistaken as hateful and angry if the recipient was predisposed to judgment and unaware of the intoxication. Regardless of whether the look was real or just sloppy, that moment was seared in Douglass’s mind. “No stronger contrast could well be present between two men than between President Lincoln and vice-president Johnson on this day,” he observed. “Mr. Lincoln was like one who was treading the hard and thorny path of duty and self-denial; Mr. Johnson was like one just from a drunken debauch. The face of the one was full of manly humility, although at the topmost height of power and pride, the other was full of pomp and swaggering vanity.”

Five weeks later, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson became the 17th president. He proved the greatest catastrophe of the eight accidental presidents, siding with remnants of the Confederacy in Reconstruction. Johnson may have been drunk during his infamous encounter with Frederick Douglass. But the prediction was spot on.