On the afternoon of July 1, 1863 – the first day of fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg – a Northern soldier propped his rifle against a tree and took careful aim at a tall, bearded Southern officer who was leading his troops forward through the woods.

The Northern soldier was Sergeant Charles H. McConnell of the 24th Michigan Infantry, whose regiment and the Iron Brigade to which it belonged had been forced to retreat from McPherson’s Ridge on the west side of Gettysburg.

As the blue-uniformed troops around him fell back, McConnell paused to fire his last round at the towering officer leading the advancing Southern troops.

[pullquote]

His target was a 27-year-old North Carolina farmer-turned-soldier, Lieutenant Colonel John R. Lane, who had taken command of the 26th North Carolina Infantry after its young colonel had been shot down.

The North Carolinians had begun their assault some 45 minutes earlier with 800 troops: now only 212 were standing.

The opposing 24th Michigan had suffered almost equally grievous losses. When Sergeant McConnell fired his last cartridge, he sent a one-ounce lead bullet smashing into the back of Lane’s neck just as the officer turned to rally his troops.

Miraculously, Lane survived.

In 1903, he was invited to give a speech at Gettysburg on the 40th anniversary of the battle. By then he was a prominent Confederate veteran and a well-known North Carolina livestock dealer.

As the aging solider prepared to deliver his speech at Gettysburg, he was joined on the stage by an elderly Chicago pharmaceutical executive and Union veteran – Charles McConnell, the Michigan soldier who had shot Lane 40 years earlier.

An unexpected encounter had brought the two together decades after the war, and they had become close friends.

“I thank God I did not kill you,” McConnell proclaimed to Lane on the stage at Gettysburg, and the two former enemies warmly shook hands.

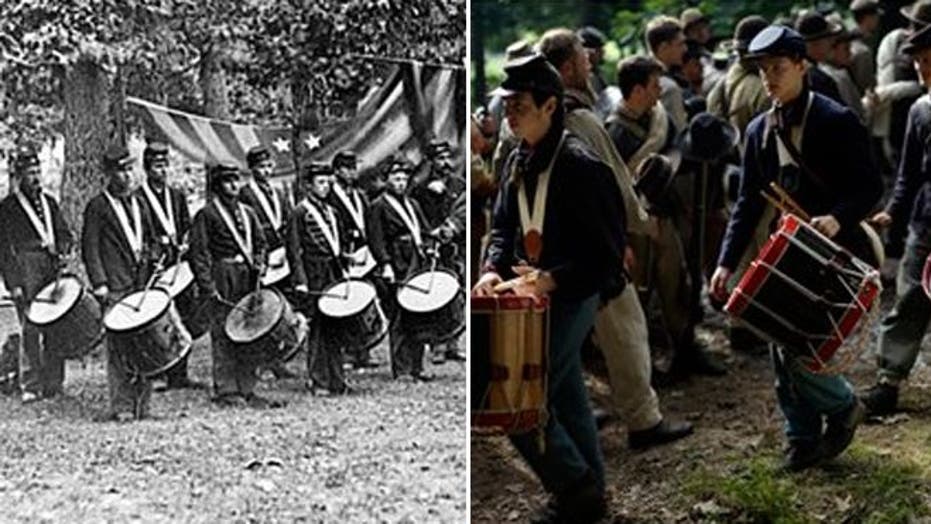

Nearby, a blue-uniformed band of Northern veterans broke into a rendition of “Dixie” as the crowd wildly cheered Lane’s and McConnell’s exceptional reconciliation.

Of all the lessons to be remembered from the Battle of Gettysburg on its 150th anniversary, one not to be ignored is the remarkable spirit of national reconciliation that followed the Civil War -- embodied by Gettysburg veterans such as McConnell and Lane.

Granted, there are lessons aplenty to be learned from Gettysburg: the disasters that can follow the failure to settle issues peacefully, the horrors and waste of warfare, the tremendous sacrifices rendered to produce the results of that war, as well as important lessons in military strategy and tactics, exceptional lessons in leadership and the inspiration of American valor, both Northern and Southern, as demonstrated on Gettysburg’s fields of fire and fury on July 1-3, 1863.

Some of those lessons can be learned from other battles and other wars, but the reconciliation of the American nation is unique.

The stunning horror of the Civil War and the ugliness, inequities and oppression of the Reconstruction Era that followed it, made reconciliation exceedingly unlikely.

Historically, civil wars do not end well. Bitterness, revenge and renewed fighting can continue for decades, even generations, producing national chaos and cultural collapse.

Not so with our Civil War.

It was followed by a national reconciliation, which was led in no small way by the nation’s veterans – those men in blue and gray who had actually fought each other, including many Gettysburg principals.

President and commander-in-chief Abraham Lincoln set the example for national reconciliation in his second inaugural address, which urged Northerners and Southerners alike to “bind up the nation’s wounds” with “malice toward none; with charity for all.”

Following Lincoln’s lead, Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant gave Confederate General Robert E. Lee generous terms at Appomattox, where Lee’s surrender triggered the end of the war.

The most influential man in the South, Lee refused to allow his army to turn to guerilla warfare, and spent the rest of his life striving to set a personal and public example of reconciliation.

Also influential was the model of reconciliation set by Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain, a Union officer who would become almost legendary for his leadership at Gettysburg.

Given the honor of overseeing the actual surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox, Chamberlain issued an extraordinary order to the Northern troops under his command. As Lee’s defeated soldiers marched forward to stack their weapons and fold their flags, there were no cheers, no jeers, no jubilation.

Instead, at Chamberlain’s order, the victorious Northern troops saluted their former foes. The startled Southern soldiers responded in kind, and the war that had claimed 620,000 lives thus ended in a mutual salute.

These key examples of reconciliation were later duplicated by countless old soldiers in blue and gray, who joined each other on the major battlefields of the war in anniversary commemorations that continued far into the 20th century.

There, on former killing fields transformed into parks, they called each other “my friend the enemy,” treated one another with mutual respect, and helped rebuild the nation.

Rooted in the Judeo-Christian values on which American culture, law and government were founded, this spirit of reconciliation did indeed “bind up the nation’s wounds” to an extraordinary degree.

Today – 150 years after Gettysburg – that spirit of reconciliation remains a lasting lesson for the ages and one that is uniquely American.