Fox News Flash top entertainment headlines for July 13

Fox News Flash top entertainment and celebrity headlines are here. Check out what's clicking today in entertainment.

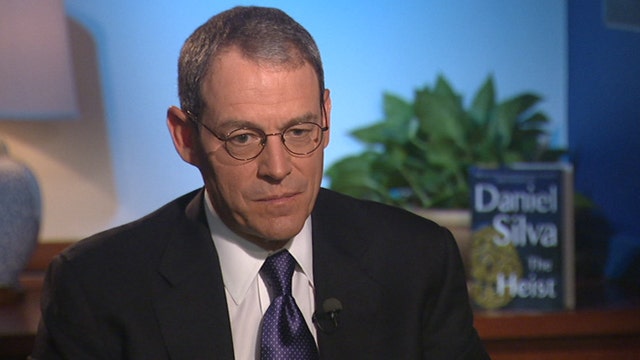

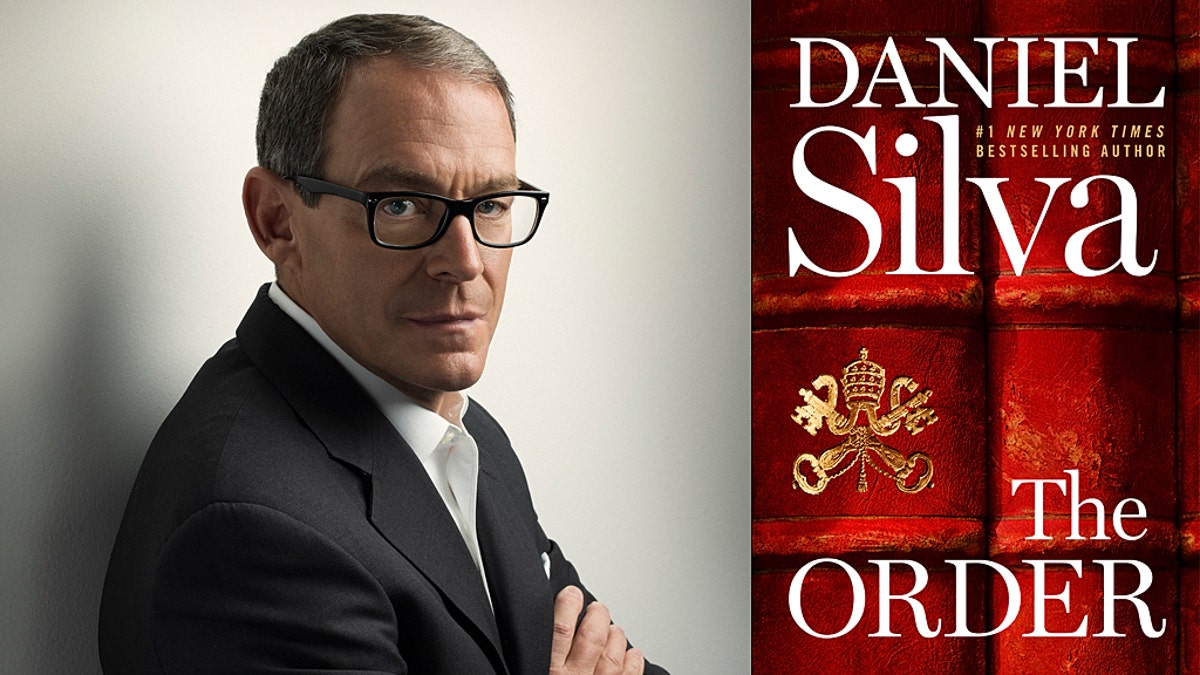

Editor's note: Daniel Silva's new thriller "The Order: A novel" features art restorer and legendary spy Gabriel Allon.

Allon has slipped quietly into Venice for a much-needed holiday with his wife and two young children. But when Pope Paul VII dies suddenly, Gabriel is summoned to Rome by the Holy Father’s loyal private secretary, Archbishop Luigi Donati. A billion Catholic faithful have been told that the pope died of a heart attack. Donati, however, has two good reasons to suspect his master was murdered. The Swiss Guard who was standing watch outside the papal apartments the night of the pope’s death is missing.

So, too, is the letter the Holy Father was writing during the final hours of his life. A letter that was addressed to Gabriel.

Chapter 1

ROME

The call arrived at 11:42 p.m. Luigi Donati hesitated before answering. The number displayed on the screen of his telefonino belonged to Albanese. There was only one reason why he would ring at such an hour. “Where are you, Excellency?” “Outside the walls.”

“Ah, yes. It’s a Thursday, isn’t it?” “Is there a problem?”

“Better not to say too much on the phone. One never knows who might be listening.”

The night into which Donati stepped was damp and cold. He was dressed in a black clerical suit and Roman collar, not the fuchsia-trimmed cassock and simar he wore around the office, which was how men of his ecclesiastical rank referred to the Apostolic Palace. An archbishop, Donati served as private secretary to His Holiness Pope Paul VII.

Tall and lean, with rich dark hair and movie-idol features, he had recently celebrated his sixty-third birthday. Age had done nothing to diminish his good looks. Vanity Fair magazine had recently christened him “Luscious Luigi.”

The article had caused him no end of embarrassment inside the backbiting world of the Curia. Still, given Donati’s well-deserved reputation for ruthlessness, no one had dared to mention it to his face. No one but the Holy Father, who had teased him mercilessly.

Better not to say too much on the phone . . .

Donati had been preparing himself for this moment for a year or more, ever since the first mild heart attack, which he had concealed from the rest of the world and even much of the Curia. But why tonight of all nights?

The street was oddly quiet. Deathly quiet, thought Donati suddenly.

It was a palazzo-lined avenue just off the Via Veneto, the sort of place a priest rarely set foot—especially a priest educated and trained by the Society of Jesus, the intellectually rigorous and sometimes rebellious order to which Donati belonged.

His official Vatican car, with its SCV license plates, waited curbside. The driver was from the Corpo della Gendarmeria, the Vatican’s 130-member police force. He headed westward across Rome at an unhurried pace.

He doesn’t know . . .

On his mobile phone Donati scanned the websites of the leading Italian newspapers. They were in the dark. So were their colleagues in London and New York.

“Turn on the radio, Gianni.” “Music, Excellency?”

“News, please.”

It was more drivel from Saviano, another rant about how Arab and African immigrants were destroying the country, as if the Italians weren’t more than capable of making a fine mess of things themselves.

Saviano had been badgering the Vatican for months about a private audience with the Holy Father. Donati, with no small amount of pleasure, had refused to grant it.

“That’s quite enough, Gianni.”

The radio went blessedly silent. Donati peered out the win- dow of the luxury German-made sedan. It was no way for a Soldier of Christ to travel.

He supposed this would be his final journey across Rome by chauffeured limousine.

For nearly two decades he had served as something like the chief of staff of the Roman Catholic Church.

It had been a tumultuous time—a terrorist attack on St. Peter’s, a scandal involving antiquities and the Vatican Museums, the scourge of priestly sexual abuse— and yet Donati had relished every minute of it.

Now, in the blink of an eye, it was over. He was once again a mere priest. He had never felt more alone.

The car crossed the Tiber and turned onto the Via della Conciliazione, the broad boulevard Mussolini had carved through Rome’s slums.

The floodlit dome of the basilica, restored to its original glory, loomed in the distance. They followed the curve of Bernini’s Colonnade to St. Anne’s Gate, where a Swiss Guard waved them onto the territory of the city-state.

He was dressed in his night uniform: a blue tunic with a white schoolboy collar, knee-length socks, a black beret, a cape against the evening chill. His eyes were dry, his face untroubled.

He doesn’t know . . .

The car moved slowly up the Via Sant’Anna—past the barracks of the Swiss Guard, the church of St. Anne, the Vatican printing offices, and the Vatican Bank—before coming to a stop next to an archway leading to the San Damaso Courtyard.

Donati crossed the cobbles on foot, boarded the most important lift in all of Christendom, and ascended to the third floor of the Apostolic Palace.

He hurried along the loggia, a wall of glass on one side, a fresco on the other. A left turn brought him to the papal apartments.

Another Swiss Guard, this one in full dress uniform, stood straight as a ramrod outside the door. Donati walked past him without a word and went inside. Thursday, he was thinking. Why did it have to be a Thursday?

Eighteen years, thought Donati as he surveyed the Holy Father’s private study, and nothing had changed. Only the telephone.

Donati had finally managed to convince the Holy Father to replace Wojtyla’s ancient rotary contraption with a modern multiline device.

Otherwise, the room was exactly the way the Pole had left it. The same austere wooden desk. The same beige chair. The same worn Oriental rug. The same golden clock and crucifix. Even the blotter and pen set had belonged to Wojtyla the Great.

For all the early promise of his papacy—the promise of a kinder, less repressive Church—Pietro Lucchesi had never fully escaped the long shadow of his predecessor.

Donati, by some instinct, marked the time on his wristwatch. It was 12:07 a.m. The Holy Father had retired to the study that evening at half-past eight for ninety minutes of reading and writing.

Ordinarily, Donati remained at his master’s side or just down the hall in his office. But because it was a Thursday, the one night of the week he had to himself, he had stayed only until nine o’clock.

Do me a favor before you leave, Luigi . . .

Lucchesi had asked Donati to open the heavy curtains covering the study’s window. It was the same window from which the Holy Father prayed the Angelus each Sunday at noon.

Donati had complied with his master’s wishes. He had even opened the shutters so His Holiness could gaze upon St. Peter’s Square while he slaved over his curial paperwork. Now the curtains were tightly drawn. Donati moved them aside. The shutters were closed, too.

The desk was tidy, not Lucchesi’s usual clutter. There was a cup of tea, half empty, a spoon resting on the saucer, that had not been there when Donati departed.

Several documents in manila folders were stacked neatly beneath the old retractable lamp.

A report from the Archdiocese of Philadelphia regarding the financial fallout of the abuse scandal.

Remarks for next Wednesday’s General Audience.

The first draft of a homily for a forthcoming papal visit to Brazil.

Notes for an encyclical on the subject of immigration that was sure to rile Saviano and his fellow travelers in the Italian far right.

One item, however, was missing.

You’ll see that he gets it, won’t you, Luigi?

Donati checked the wastebasket. It was empty. Not so much as a scrap of paper.

“Looking for something, Excellency?”

Donati glanced up and saw Cardinal Domenico Albanese eyeing him from the doorway.

Albanese was a Calabrian by birth and by profession a creature of the Curia. He held several senior positions in the Holy See, including president of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, and archivist and librarian of the Holy Roman Church.

None of that, however, explained his presence in the papal apartments at seven minutes past midnight. Domenico Albanese was the camerlengo. It was his responsibility alone to issue the formal declaration that the throne of St. Peter was vacant.

“Where is he?” asked Donati.

“In the kingdom of heaven,” intoned the cardinal. “And the body?”

Had Albanese not heard the sacred calling, he might have moved slabs of marble for his living or hurled carcasses in a Calabrian abattoir.

Donati followed him along a brief corridor, into the bedroom. Three more cardinals waited in the half-light: Marcel Gaubert, José Maria Navarro, and Angelo Francona.

Gaubert was the secretary of state, effectively the prime minister and chief diplomat of the world’s smallest country. Navarro was prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, guardian of Catholic orthodoxy, defender against heresy. Francona, the oldest of the three, was the dean of the College of Cardinals. As such, he would preside over the next conclave.

It was Navarro, a Spaniard of noble stock, who addressed Donati first. Though he had lived and worked in Rome for nearly a quarter century, he still spoke Italian with a pronounced Castilian accent. “Luigi, I know how painful this must be for you. We were his faithful servants, but you were the one he loved the most.”

Cardinal Gaubert, a thin Parisian with a feline face, nodded profoundly at the Spaniard’s curial bromide, as did the three laymen standing in the shadow at the edge of the room: Dr. Octavio Gallo, the Holy Father’s personal physician; Lorenzo Vitale, chief of the Corpo della Gendarmeria; and Colonel Alois Metzler, commandant of the Pontifical Swiss Guard.

Donati, it seemed, was the last to arrive. It was he, the private secretary, who should have summoned the senior princes of the Church to the bedside of the dead pope, not the camerlengo. Suddenly, he was racked by guilt.

But when Donati looked down at the figure stretched upon the bed, his guilt gave way to overwhelming grief.

Lucchesi was still wearing his white soutane, though his slippers had been removed and his zucchetto was nowhere to be seen.

Someone had placed the hands upon the chest. They were clutching his rosary. The eyes were closed, the jaw slack, but there was no evidence of pain on his face, nothing to suggest he had suffered.

Indeed, Donati would not have been surprised if His Holiness woke suddenly and inquired about his evening.

He was still wearing his white soutane . . .

Donati had been the keeper of the Holy Father’s schedule from the first day of his pontificate.

The evening routine rarely varied. Dinner from seven to eight thirty. Paperwork in the study from eight thirty until ten, followed by fifteen minutes of prayer and reflection in his private chapel.

Typically, he was in bed by half past ten, usually with an English detective novel, his guilty pleasure. "Devices and Desires" by P. D. James lay on the bedside table beneath his reading glasses. Donati opened it to the page marked.

Forty-five minutes later Rickards was back at the scene of the murder . . .

Donati closed the book. The supreme pontiff, he reckoned, had been dead for nearly two hours, perhaps longer. Calmly, he asked, “Who found him? Not one of the household nuns, I hope.”

“It was me,” replied Cardinal Albanese. “Where was he?”

“His Holiness departed this life from the chapel. I discovered him a few minutes after ten. As for the exact time of his passing . . .” The Calabrian shrugged his heavy shoulders. “I cannot say, Excellency.”

“Why wasn’t I contacted immediately?” “I searched for you everywhere.”

“You should have called my mobile.”

“I did. Several times, in fact. There was no answer.”

The camerlengo, thought Donati, was being untruthful. “And what were you doing in the chapel, Eminence?”

“This is beginning to sound like an inquisition.” Albanese’s eyes moved briefly to Cardinal Navarro before settling once more on Donati. “His Holiness asked me to pray with him. I accepted his invitation.”

“He phoned you directly?”

“In my apartment,” said the camerlengo with a nod. “At what time?”

Albanese lifted his eyes to the ceiling, as though trying to recall a minor detail that had slipped his mind. “Nine fifteen. Perhaps nine twenty. He asked me to come a few minutes after ten. When I arrived . . .”

Donati looked down at the man stretched lifeless upon the bed. “And how did he get here?”

“I carried him.” “Alone?”

“His Holiness bore the weight of the Church on his shoulders,” said Albanese, “but in death he was light as a feather. Because I could not reach you, I summoned the secretary of state, who in turn rang Cardinals Navarro and Francona. I then called Dottore Gallo, who made the pronouncement. Death by a massive heart attack. His second, was it not? Or was it his third?”

Donati looked at the papal physician. “At what time did you make the declaration, Dottore Gallo?”

“Eleven ten, Excellency.”

Cardinal Albanese cleared his throat gently. “I’ve made a slight adjustment to the time line in my official statement. If it is your wish, Luigi, I can say that you were the one who found him.”

“That won’t be necessary.”

Donati dropped to his knees next to the bed. In life, the Holy Father had been elfin. Death had diminished him further.

Donati remembered the day the conclave unexpectedly chose Lucchesi, the Patriarch of Venice, to be the two hundred and sixty-fifth supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church.

In the Room of Tears he had chosen the smallest of the three ready-made cassocks. Even so, he had seemed like a small boy wearing his father’s shirt. As he stepped onto the balcony of St. Peter’s, his head was barely visible above the balustrade. The vaticanisti christened him Pietro the Improbable. Church hard-liners had referred to him derisively as Pope Accidental.

After a moment Donati felt a hand on his shoulder. It was like lead. Therefore, it had to be Albanese’s.

“The ring, Excellency.”

It was once the responsibility of the camerlengo to destroy the dead pope’s Ring of the Fisherman in the presence of the College of Cardinals. But like the three taps to the papal forehead with a silver hammer, the practice had been done away with.

Lucchesi’s ring, which he seldom wore, would merely be scored with two deep cuts in the sign of the cross. Other traditions, however, remained in place, such as the immediate locking and sealing of the papal apartments. Even Donati, Lucchesi’s only private secretary, would be barred from entering once the body was removed.

Still on his knees, Donati opened the drawer of the bedside table and grasped the heavy golden ring. He surrendered it to Cardinal Albanese, who placed it in a velvet pouch. Solemnly, he declared, “Sede vacante.”

The throne of St. Peter was now empty. The Apostolic Constitution dictated that Cardinal Albanese would serve as temporary caretaker of the Roman Catholic Church during the interregnum, which ended with the election of a new pope.

Donati, a mere titular archbishop, would have no say in the matter. In fact, now that his master was gone, he was without portfolio or power, answerable only to the camerlengo.

“When do you intend to release the statement?” asked Donati.

“I was waiting for you to arrive.” “Might I review it?”

“Time is of the essence. If we delay any longer . . .”

“Of course, Eminence.” Donati placed his hand atop Lucchesi’s. It was already cold. “I’d like to have a moment alone with him.”

“A moment,” said the camerlengo.

The room slowly emptied. Cardinal Albanese was the last to leave.

“Tell me something, Domenico.”

The camerlengo paused in the doorway. “Excellency?” “Who closed the curtains in the study?”

“The curtains?”

“They were open when I left at nine. The shutters, too.”

“I closed them, Excellency. I didn’t want anyone in the square to see lights burning in the apartments so late.”

“Yes, of course. That was wise of you, Domenico.”

The camerlengo went out, leaving the door open. Alone with his master, Donati fought back tears. There would be time for grieving later.

He leaned close to Lucchesi’s ear and gently squeezed the cold hand. “Speak to me, old friend,” he whispered. “Tell me what really happened here tonight.”

From the book "THE ORDER: A Novel" by Daniel Silva. Copyright 2020 by Daniel Silva. Reprinted by permission of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.