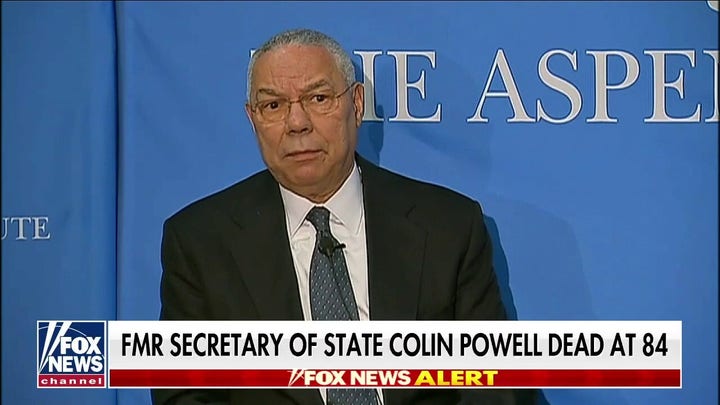

KT McFarland on Colin Powell's wisdom, 'great lessons for life'

Former Deputy National Security Advisor K.T. McFarland joined 'Fox & Friends' following the news of Colin Powell's passing Monday.

I first met Colin Powell, who died Monday, in the Pentagon in the early years of the Reagan administration.

He was Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger’s military assistant; I was the secretary’s speechwriter. We were in and out of each other’s offices a dozen times every day. We were an odd pair in those days—there weren’t many Black flag officers and even fewer women in Pentagon senior leadership.

Gen. Colin Powell almost wasn’t—a general, that is. After Vietnam, he was passed over for promotion. But it had nothing to do with his record in Vietnam, which was exceptional. A poor kid from the Bronx, and son of Jamaican immigrants, Powell wasn’t part of the "old boy" West Point network. But President Lyndon Johnson’s Secretary of the Army insisted they add several men of color to the promotion list. A few years and promotions later, Gen. Powell was in the inner circle of the Reagan administration.

During those years, Weinberger was worried the U.S. might again be drawn into another war we couldn’t win—this time in the Middle East. Weinberger got permission from President Ronald Reagan to lay out a warfighting doctrine for the post-Vietnam world, and he asked me to draft a speech.

More from Opinion

I went to Powell, and asked him about lessons learned in Vietnam. He talked about the frustrations of fighting in a war with vague and ever-changing objectives, and without the support of the American people. He spoke for many in his generation of veterans: if America went to war, it should be for good reason—and we should win.

My speech draft became known as Weinberger Principles of War, which President Reagan endorsed. It set out a series of guidelines for when and how the U.S. should go to war, with clearly defined goals, objectives, and resources. The United States should only go to war in defense of our vital national interests, with the support of the American people, and with overwhelming resources. And we should fight to win.

Fast forward a decade, Powell was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the first Gulf War. We fought and won that war by following those same principles.

Fast forward another decade to September 11, 2001. We went into Afghanistan and destroyed all but of handful of al Qaeda in a few short months. President George W. Bush’s neoconservative advisers pushed to invade Iraq, convinced Saddam Hussein’s possessed and was getting ready to use weapons of mass destruction.

Secretary of State Powell was less convinced, but reluctantly agreed to go to the United Nations and make the case for attacking Iraq, deposing Saddam Hussein, and destroying his weapons of mass destruction. He later said it was one of the biggest mistakes of his life.

In the end there were no weapons of mass destruction, but we stayed in Iraq, as we did in Afghanistan. As Powell predicted, it was a disaster. His plans for a post-Saddam self-governing Iraq were tossed aside. The neoconservatives wanted to build modern democracy, and permanent U.S. bases. But history has a way or repeating itself—Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan. We started with the best of intentions, but we ultimately failed.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

After leaving the Bush administration, Powell left politics and public life largely behind. He mentored young people, joined some corporate boards, wrote a few bestselling books—including one that set out the principles which guided him, in public service and private life.

Another of his books uses his own life story as a template for everything that is great about America. A poor black kid from the Bronx, son of immigrants, rises to become an iconic American hero.

That wasn’t just Powell’s American journey. It is our American journey.

To me, Powell represents what our military can and should be. Non-political, fiercely patriotic, ambitious for nation but not for self. He believed we needed a strong military, not for conquest, but to deter our enemies from attacking us. He embodied Reagan’s "Peace through Strength."

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In many ways, Powell seems to have lived a lifetime ago. The lessons he learned and the principles he lived by have been forgotten the current generation of military and civilian leaders. It’s time to dust them off. They would be a good place to start as we struggle to redefine our military, our adversaries, and our national purpose.

It would be Colin Powell’s final—and greatest—gift to us all.