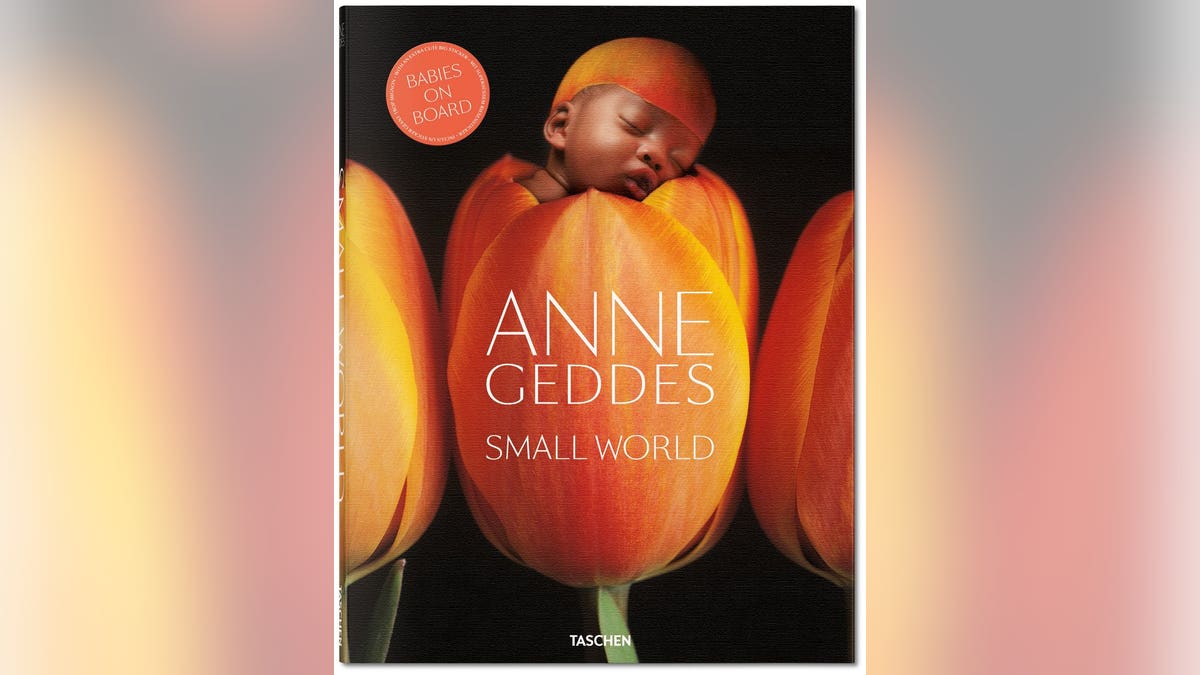

(Anne Geddes, Small World)

Editor's note: This extract by Holly Stuart Hughes is taken from Anne Geddes. Small World, published by TASCHEN (2017).

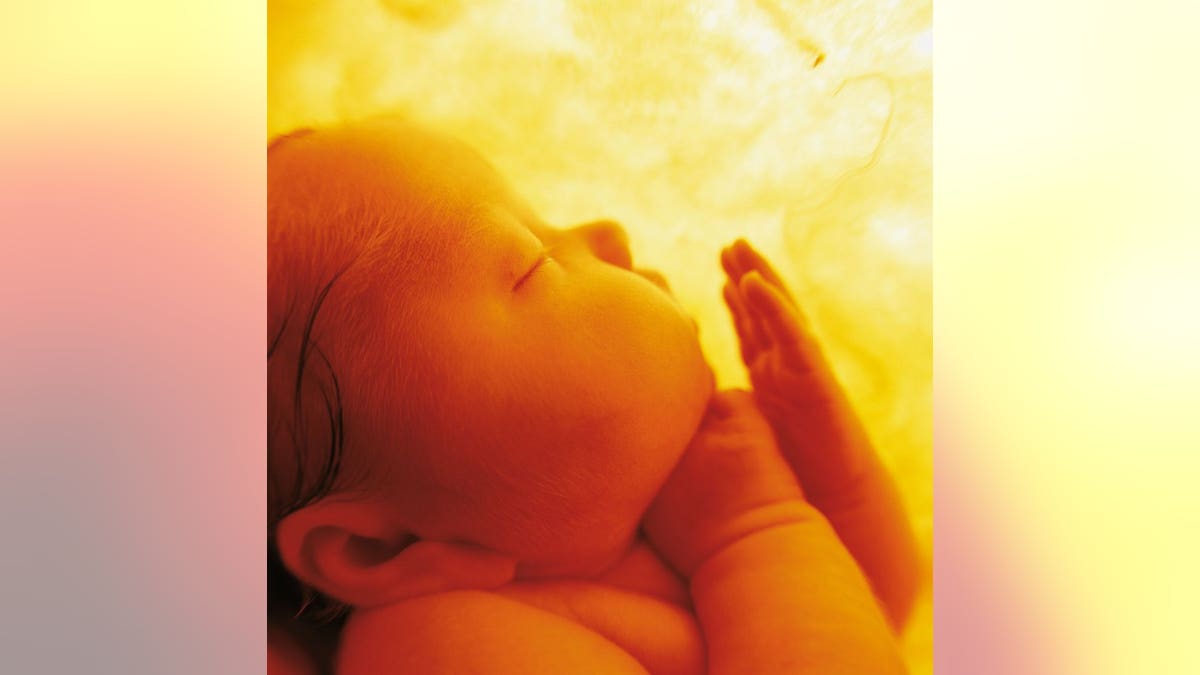

“There’s only goodness around babies and that’s what I’m fascinated by,” Anne Geddes says. “It’s just human purity right there.” For the three decades she has been making photographs, Geddes has dedicated herself to exploring the wonder and innocence of new life, mining her memories, dreams, and observations of nature for new inspirations and new symbols through which she expresses her thoughts and emotions about motherhood and childhood.

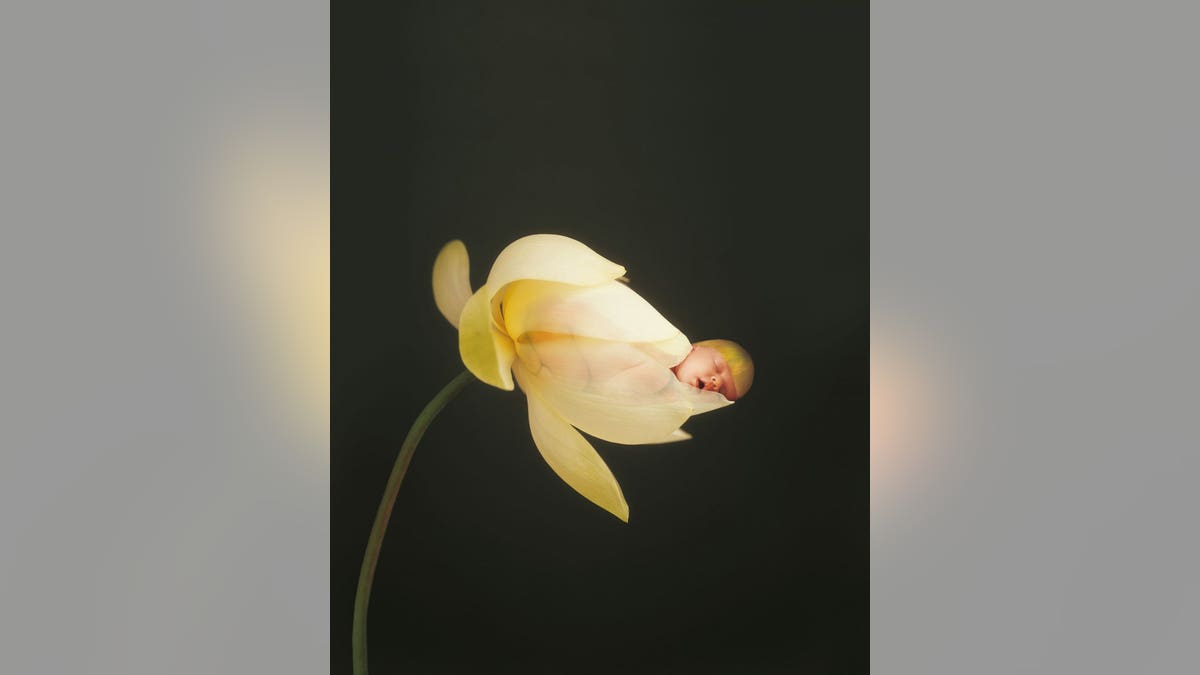

Each of her photographs begins with a seed of an idea she wants to convey, or a puzzle she wants to examine: How can she best highlight the soft folds of a baby’s legs or the peaceful expression of a sleeping newborn? How can she bring a children’s storybook or fairy tale to life? How can she celebrate the beauty of a pregnant woman’s curved belly? She makes sketches, then experiments, and, finally, crafts her composition.

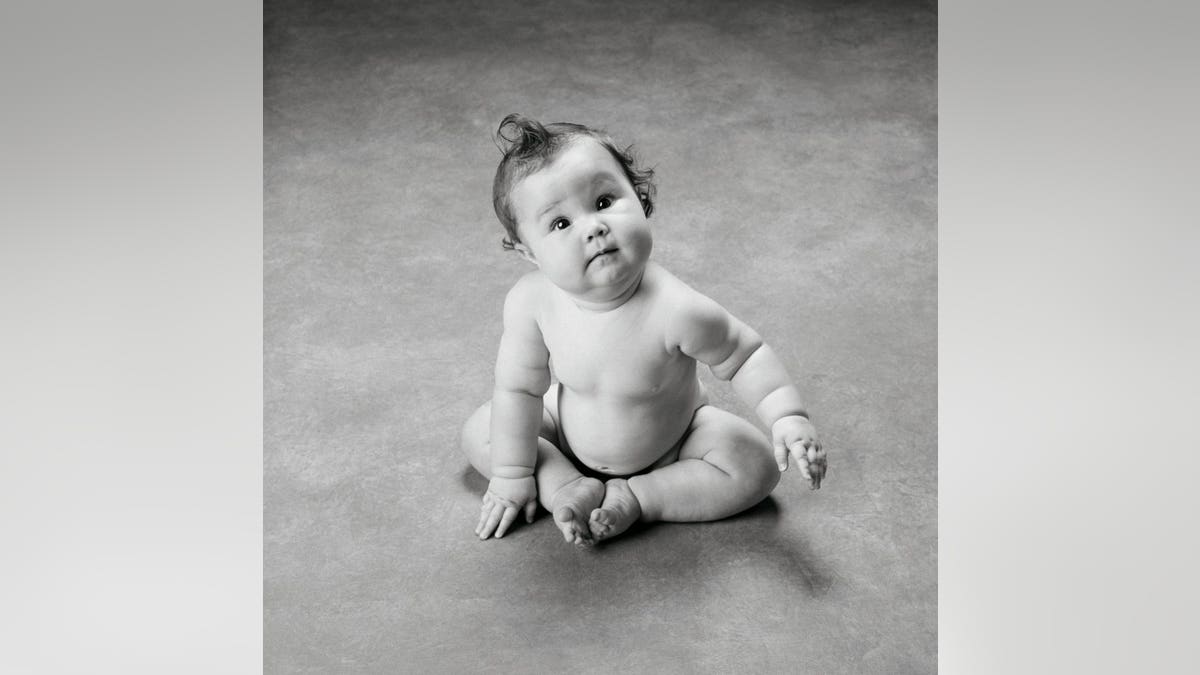

This book draws on the large archive of photographs Geddes has created over the course of her prolific career to show the many approaches she has taken to portray each stage of early human development. Her interest in what she calls “new life” has inspired her to photograph pregnancy, newborns blissfully and peacefully unaware of the world around them, babies who are beginning to sit up and take stock of their fingers and toes, and children taking steps to look around and to express the force of their personalities on the world.

Geddes has transformed the photography of motherhood and childhood. Early in her career, while making commissioned portraits for parents, she broke from the tradition of portraying children as miniature adults, stiffly posed in their Sunday best. She told parents not to worry if their kids balked at smiling for her camera. “I’d say, ‘When you look at this in 20 or 30 years’ time, you’ll want to remember the 2-year-old who didn’t want to wear matching socks that day.’” She has remained true to the honesty of this approach, whether she’s shooting elaborate productions or contemplative studies of form. Her imagery is immediately recognizable and, thanks to the popularity of her books, cards, and calendars, she’s the rare photographer whose name is almost as famous as her most famous photos. Her success has inspired imitation as well as parody.

Typically, photographers who achieve popular success for their work on one subject choose to recreate their greatest hits again and again. Geddes, however, has followed her interests. Ignoring imitators and critics, she remains committed to photographing what delights her.

“I do keep evolving and changing,” she notes. After she completes one long-term series, she seeks a new creative challenge. With each new series, she has honed new techniques for lighting and composing her images, varying her style from the contemplative to the whimsical.

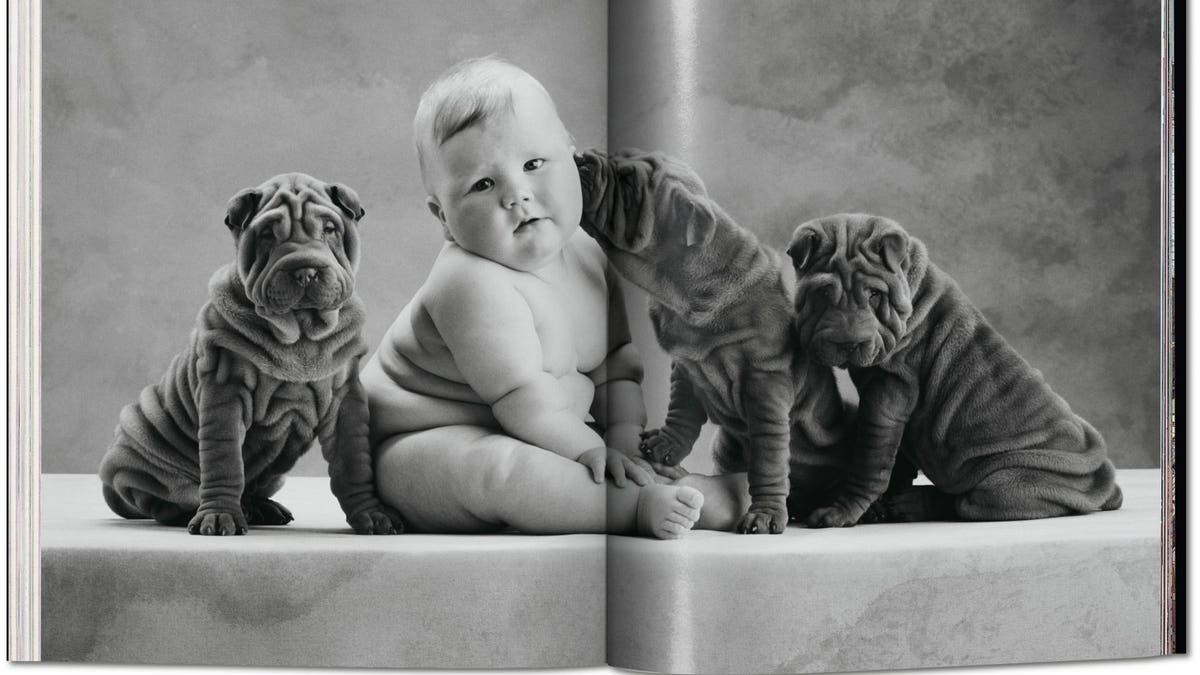

Geddes notes that the “gentle humor” in many of her best-known images has often been overlooked. While she insists that her approach is often lighthearted, she takes her craft and her choice of subject matter very seriously. Babies, she argues, “are so important to the world. They change people’s lives. They turn women into mothers and men into fathers. They make families.”

Shortly after midnight on New Year’s 1984, Geddes said out loud, “I’m going to be the best-known baby photographer in the world.” At the time, she had little reason for such confidence. She was self-taught and her sole experience as a working photographer had been making portraits of children for friends and neighbors. She had taken a break from the work following the birth of her first daughter and her family’s move to Sydney. When her daughter was two, Geddes picked up the camera again to make baby and family portraits, which she sold as customized Christmas cards. She shot all her photos outdoors or in available light, and her first efforts were unpolished, but they evidenced a knack for capturing kids’ personalities.

In 1986, Geddes, pregnant with her second daughter, saw a newspaper ad for a children’s portrait studio. That year, she contacted the photographer, and offered her services as an assistant. Learning how to work with artificial lighting and a 4x5 camera expanded her sense of what she could achieve with her photography. With confidence in her new skills, she set up her own studio in her garage at home in 1987. Her husband, Kel, a television executive, had her name put on a plaque that he hung on the garage door. His next job took the family to Auckland, New Zealand, where Geddes opened a new studio. The upbeat honesty and humor of her unposed portraits of babies and kids made them unique at the time. A New Zealand monthly magazine published an article on her commissioned portraits, along with one of her photos. Her new business took off.

Geddes credits her 10 years shooting commissioned portraits with teaching her how to coax and corral kids of every age. With time, however, she chafed at the limitations of the genre and the stress of meeting parents’ expectations. “I used to say that even if I charged a million dollars for a portrait session, there’s not a lot you can do with a 2-year-old who’s having a bad day,” she says. To fuel her creativity and “to save my sanity,” she says, she resolved in 1990 to create a photo a month just for herself.

Her first two experiments established the twin paradigms for the styles all her subsequent work has followed: One is the classically composed study of form, and the other is the imaginative illustration that tells a story within a single frame. Her first personal image was a black-and-white portrait of a sleeping four-month-old named Joshua, wrapped in swaddling cloths that are suspended from a big hook, as if he were being weighed. The idea, Geddes says, came from New Zealand’s Plunket Society, an aid organization that provides nutrition and health advice to new parents, which would weigh newborns in cloth diapers on a suspended scale.

The elements that make the Joshua image striking—the graphic elegance, the stark backdrop, the simple props that highlight the baby’s delicacy and tiny size—reappear in numerous photos Geddes has shot over the years. The quiet simplicity of her photo of a man’s hands gently clasping a premature and underweight baby, and her series of sleeping newborns cocooned in black silk against backdrops, can be traced back to the Joshua portrait. Geddes calls these studies her “classic images.” They are, she says, “just about the babies: Look at this, how small and how beautiful they are.”

With her second personal experiment, Geddes made her first attempt at taking a whimsical, illustrative approach. She had in mind the story that generations of parents told their children when they asked where babies come from: They’re found in a cabbage patch, the story says. Geddes used heads of cabbage as her props. She wrapped cabbage leaves around containers, then seated seven-month-old twins Rhys and Grant into the center of each container. With cabbage leaves on their heads, they look at each other in puzzlement. The droll image is still one of Geddes’s most recognizable creations. It contains many of the elements for which Geddes is known: the juxtaposition of babies and props, humor, surprise, nature, and allusions to a well-known legend. The babies become the heroes of the story she tells within a single frame. Geddes explains, “They’re like characters in my world, my imaginary world.”