Jared Cohen: Lessons in Leadership from the Accidental Presidents

Drawing on the examples of Harry S. Truman and Lyndon B. Johnson, Jared Cohen explains how we can learn from how both presidents approached getting advice and incorporating the advisers from their predecessor.

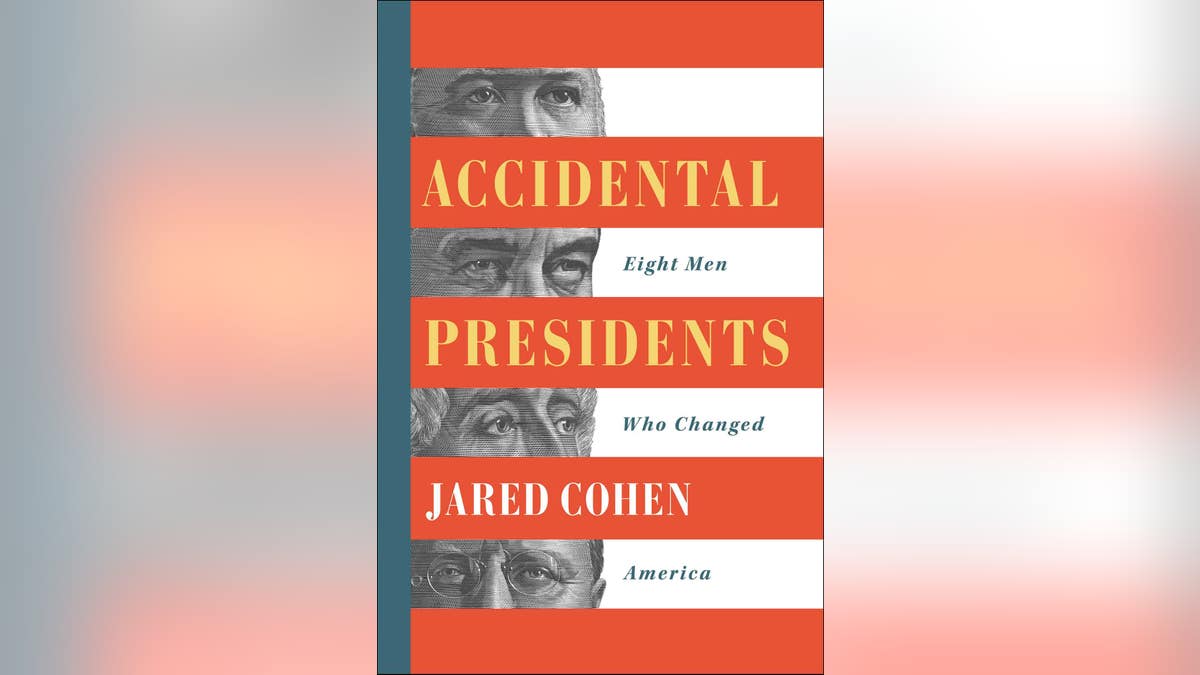

We succeed and fail by the advice we get and whom we listen to. Today, it seems that there is unprecedented interest in consuming advice and lessons, yet we might be overlooking some of the most important and insightful case studies. I stumbled into them during a five-year indulgence writing “Accidental Presidents," about eight men who became president upon the death of their predecessor – history altered by a heartbeat.

We can learn a lot from the triumphs and failures of these men, who were neither the voters’ nor their party’s choice.

A must-read case study is Harry Truman, who inherited a greater burden and with less preparation than any accidental president in history.

Everyone knew Truman would be president, even his predecessor Franklin Roosevelt. It wasn’t discussed, nor was it acknowledged by the president, who made no effort to get to know the man who would almost certainly succeed him. During Truman’s 82 days as vice president, he saw FDR twice, he never received a foreign policy or war briefing, hadn’t stepped foot in the map room where all the war planning happened, didn’t get debriefed on the happenings at Yalta or the Manhattan Project, and had no exposure to any of the leaders who would shape the post-war order.

On April 12, 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt informed Harry Truman that her husband was dead. “Is there anything I can do for you?” Truman asked, to which she responded, “Is there anything we can do for you? For you are the one in trouble now.” As the realities of the moment sank in, Truman quickly realized she was right.

On his first day as president, Truman told reporters, “I felt as though the moon and the stars and all the planets fell on me last night when I got the news [of FDR’s death]. I have the most terribly responsible job any man ever had.”

He wasn’t wrong. He lacked the subject matter expertise to fight the war and had at best a novice’s understanding of what it would take to win the peace. “I was beginning to realize,” he would later write, “how little the Founding Fathers had been able to anticipate the preparations necessary for a man to become President so suddenly.”

Harry Truman faced a daunting set of challenges. The war in Europe persisted and while the Germans were on the defensive and victory seemed likely, it was unclear what that would look like and at what price. Hitler was still alive and commanding the Nazis from his bunker. Roosevelt’s relationship with Churchill had been complex and the two had not seen eye-to-eye on Russia. Stalin appeared to be reneging on every promise he had made at Yalta and was proving unpredictable at best, villainous at worst.

There was also the Pacific theater, which raged on. War with Japan was still a fierce fight and the U.S. was faced with the grim prospect of having to move over 1 million men from the European theater for an invasion of Japan in November. A ferocious battle for Okinawa had already commenced and would prove to be one of the bloodiest in U.S. history. Bureaucratic battles between the Army and Navy were undermining the war effort. And the new president had to digest having just been briefed on the Manhattan Project and grapple with how to make use of a new weapon capable of unleashing unimaginable destruction.

Harry Truman had been a machine politician from Missouri whom everybody underrated, including himself. But part of what made Truman successful is that he was remarkably decisive, both about his policies and his choice of advisers. His ability to make monumental decisions during his first year in office showed tremendous confidence and continued throughout his presidency. His quick decisions about whom he should listen to were equally impressive.

By the end of Truman’s first term, he could point to a long list of accomplishments – more than most presidents achieve in an entire term. He had ended World War II (including making the tough decision to drop the atomic bomb just four months into his term), launched the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe, succeeded where Woodrow Wilson had failed in establishing the United Nations, recognized the state of Israel, authorized the Berlin airlift, and signed the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, which filled key constitutional gaps. He also desegregated the military through Executive Order 9981.

In 1948 he became president in his own right. With his successes, Harry Truman had written the playbook on leading under pressure. He had impossible shoes to fill, but he had the right team around him.

FDR was revered by his advisers and they preferred to think of him as immortal, rather than acknowledge the reality that he was dying. When he died 11 weeks into his fourth term, this group of loyal Europeanists sought to carry out Roosevelt’s vision with Truman as their like-minded new chief executive. These were men who wanted to save Europe, which required Truman to be successful.

The new president knew very little about foreign policy, but he was a patriot and shared their vision. This alignment meant that he trusted their advice and listened to them, while they put faith in his ability to learn fast and lead. They didn’t waste time questioning whether he could sit with Stalin, manage Churchill, or make the big decisions. They helped him do it, which is part of why he proved so decisive.

When they advised him to leave the postwar future of Japan to General Douglas MacArthur, he adhered. When they urged him to focus his attention on Europe, he followed their advice. When they explained that the atomic bomb could save more than a million American lives, he trusted their motives. He made some of his biggest decisions in just the first nine months, which reinforced trust and confidence.

In this sense, Truman was lucky, since they guided him well and were all in it for the long haul. George H. W. Bush summed-up this success, telling me, “It turned out, Truman did a fine job. Thank heavens. We all assumed we were training for the invasion of Japan. I always felt Harry saved our lives.”

Truman was dealt an undeniably good hand on foreign policy, but he should still be credited for his cabinet savvy and ought to be a prescriptive case study for success.

The lessons from Lyndon B. Johnson are far more sobering.

LBJ inherited a very different hand from his predecessor, John F. Kennedy, than Truman did from FDR, and his fatal flaw was not recognizing this. Truman’s approach wouldn’t work with Kennedy’s particular cabal of advisors and the Vietnam War context. Johnson should have gotten rid of the Kennedy crowd, who perhaps in pursuit of their own agendas – or out of fear for how he would react to the truth – gave him misguided information about Vietnam.

Lyndon Johnson lacked the courage in foreign policy that he exhibited on civil rights, which is part of why he kept Kennedy’s advisers. He was determined to be a great domestic president and foreign policy crises were an unfortunate reality that he had to address. At first, this meant resisting further escalation and holding out for a peaceful settlement. But soon, fearing he would be the one to lose Vietnam, he escalated and then escalated further.

A failure in leadership has consequences and the tragedy for Johnson is that Vietnam overshadows his domestic achievements, most notably the civil rights acts of 1964, 1965 and 1968. The loss for the country is that had Vietnam not gone south, LBJ may have had another four years in office to continue advancing civil rights. Had this happened, he would have died just two days after leaving office in 1969.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Most presidents go into office hoping to do great things. Sometimes circumstances or missteps make them do things that are not great, that are foolish or disastrous. We cannot diminish what Johnson did on the domestic side. He was a president who thought big about trying to change America. Some of it worked and some of it didn’t. The part that worked left an indelible mark on the country that would be felt for decades to come.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE IN JARED COHEN'S "ACCIDENTAL PRESIDENTS" SERIES, AND KEEP VISITING FOXNEWS.COM/OPINION FOR MORE BOOK EXCERPTS.

Excerpted from "Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America" by Jared Cohen (Simon & Schuster, April 9, 2019)