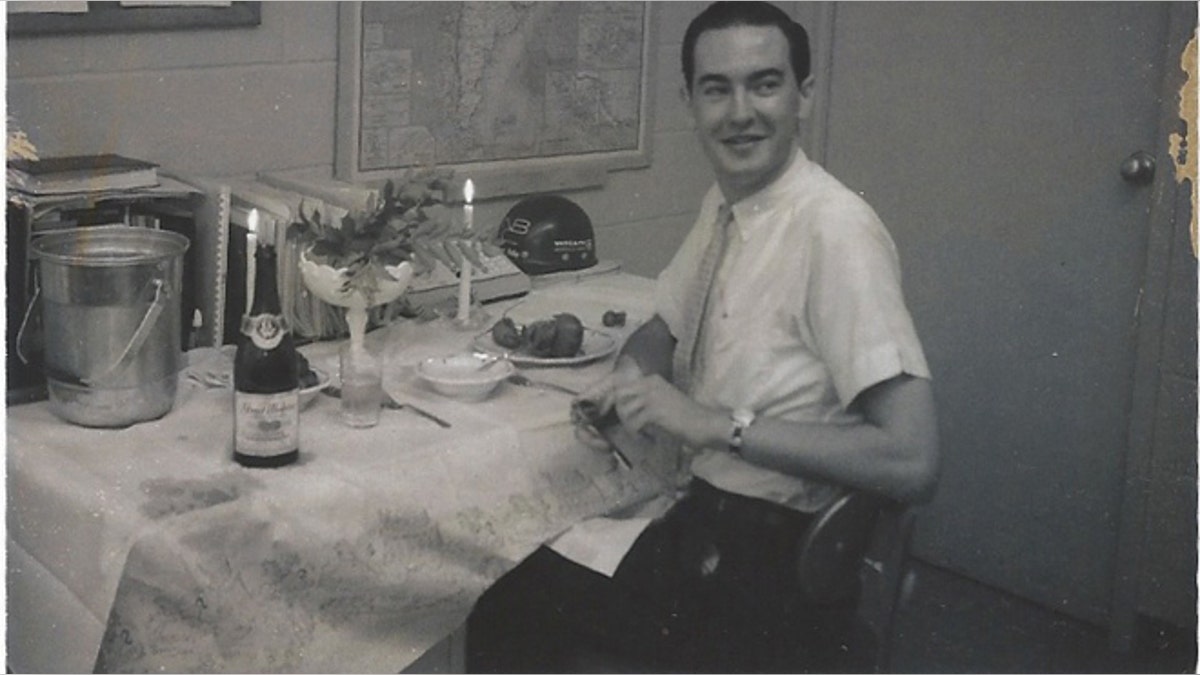

Cal Thomas as a 20-year-old copy at NBC in Washington. (Courtesy of the author)

My parents voted for Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election. I had not yet developed a political worldview, but as a freshman at American University in Washington, D.C., I stayed up late to watch the election returns slowly trickle in before going to bed at 2 a.m. with the outcome still undecided.

The following year I was hired as a copyboy at NBC News, delivering wire service “copy” to news reporters in the network’s Washington bureau. White House correspondent Sander Vanocur invited me to accompany him to observe the swearing-in of Adlai Stevenson as the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

President Kennedy was there. It was the first time I had seen a president in person. My mother had told me about visits she and her parents had made to the White House when Calvin Coolidge was president, but this was something new for me.

[pullquote]

After the Eisenhower years, my impression of the man was similar to that of many others: Kennedy looked so young.

Two years later on the way to work, Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, I stopped at a traffic light on River Road in Bethesda, Md. It was 1:30 p.m. Eastern Time. A bulletin interrupted the music I was listening to on the car radio. President Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. My first reaction was to roll down my car windows and shout to other motorists, “The president has been shot!” I then raced to the bureau where it was controlled chaos for the next four days.

The 1960s are often called the “Golden Age” of broadcast journalism. One reason is that the networks were composed mainly of men who were writers with experience at newspapers or wire services. Some had reported on World War II. They became my mentors. Working alongside them was my master class.

On that unforgettable day, as I was reviewing the Associated Press wire coverage, I saw something I had never seen before. “Flash,” the bulletin read, “Kennedy seriously wounded, perhaps fatally, by assassin’s bullet.” Flash was a designation reserved for only the most catastrophic events. The time on the wire copy was 12:39 p.m. Central Time. Less than an hour later, there was another “Flash.” “President Kennedy Dead.”

I saved copies of the wire bulletins and tucked them neatly inside the book “Four Days,” a historical record of President Kennedy’s death. Re-reading UPI White House Correspondent Merriman Smith’s reporting from Dallas with the limited technology of the time is a testament to what great journalism once looked like. His stories are in the book.

Also included in “Four Days” is an essay by the late historian Bruce Catton whose words written just weeks after the assassination cut through a lot of the analysis and gets to the true legacy of this personally flawed, but fascinating man:

“What John F. Kennedy left us was most of all attitude,” he wrote. “To put it in the simplest terms, he looked ahead. He knew no more than anyone else what the future was going to be like, but he did know that that was where we ought to be looking. Only to a certain extent are we prisoners of the past. The future sets us free. It is our escape hatch. We can shape it to our liking, and we had better start thinking about how we would like it.”

Ronald Reagan would embrace a similar futuristic outlook.

What followed Kennedy’s assassination was an era of growing and more expensive government, race riots, the divisive Vietnam War and social disintegration. It was not the hopeful future Kennedy envisioned, but Bruce Catton’s words remind us we can always start over by using the future as an “escape hatch.”