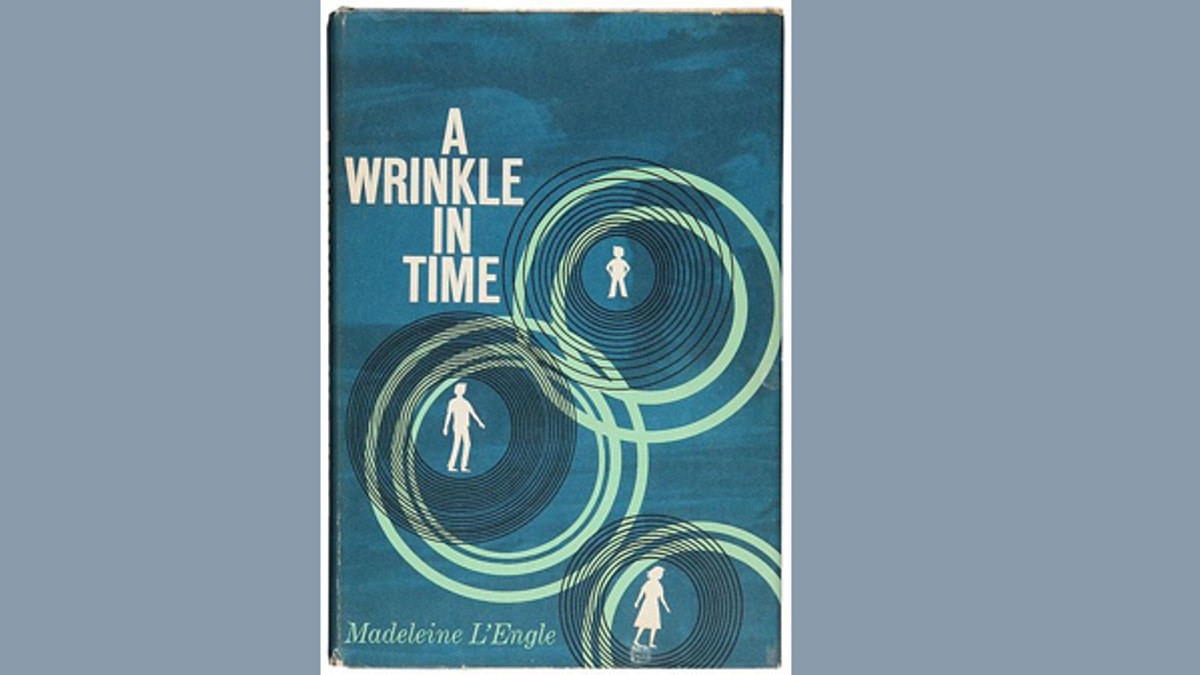

In September 1962—fifty years ago this month—my third-grade class filed into the school library in search of adventure. I found mine almost immediately—a book displayed on the "new arrivals" shelf. It had a blue cover with three children silhouetted against radiating concentric circles.

I snatched the book off the shelf and printed my name in the first space on the card in the pocket. I was the first student at John C. Fremont Elementary School to check out "A Wrinkle in Time" by Madeleine L'Engle. It was L'Engle's first published novel, and it would go on to win many awards, including the prestigious Newbery Medal. (L'Engle, who died in 2007, also received the National Humanities Medal in 2004.)

At the tender age of nine, I was already a science-fiction addict, having been hooked years earlier on black-and-white TV space operas like Tom Corbett—Space Cadet. I was hungry for science fiction to read, yet our school library had little to offer. So the discovery of "A Wrinkle in Time" had a huge impact on me.

[pullquote]

It would not be an exaggeration to say that "A Wrinkle in Time" helped set the course of my life. I'm a writer today in large part because that novel captured my imagination when I was a boy. I have re-read it many times, and with each new reading, my appreciation has deepened.

As a boy, I was lost in the adventure tale of good versus evil, of children on a quest to save their father, who was lost in time and space. I was enthralled by those mysterious angelic beings named Mrs Whatsit, Mrs Who, and Mrs Which—and the deadly telepathic entity known only as IT.

Re-reading the novel as an adult, I've been even more impressed to note how L'Engle seamlessly wove together concepts from quantum physics and the Christian faith. "A Wrinkle in Time" contains allusions to Isaiah, Psalms, and the New Testament. Mrs Who quotes from 1 Corinthians: "But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty" (1 Corinthians 1:27).

The inspiring notion that God is pleased to use foolish, weak creatures like ourselves as His instruments to topple the mighty and powerful also runs through the fantasy of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien (and, I might add, this theme is central to my own "Timebenders" science-fantasy series). I can personally attest that readers, both young and old, draw hope and optimism from these books to live their lives with a sense of mission, purpose, and confidence.

"A Wrinkle in Time" introduced my young mind to the concept of paradoxes, which are common in both physics and faith. For example, L'Engle employs an idea called a "tesseract" or "hypercube," a geometric construct consisting of four dimensions of space and one dimension of time. L'Engle uses the tesseract as a device to warp space and permit faster-than-light travel.

L'Engle paid a heavy price in rejection letters for aiming such mind-expanding concepts at a young audience. The book was rejected more than forty times before it was accepted by Farrar, Straus & Giroux for a June 1962 release. L'Engle's refusal to dumb her story down was vindicated by generations of avid, grateful readers.

Even as a nine-year-old reader, I found strange and intoxicating ideas like the tesseract essential to the book's appeal. When I wrote my "Timebenders" series for young readers, L'Engle's example emboldened me to include some challenging concepts of my own. My editors, to their credit, agreed that my readers could handle a little quantum physics with their fantasy.

Fifty years ago, my life was changed by a book. If you've never experienced "A Wrinkle in Time," now would be a good time to discover it its wonders. And if you're already a fan, it just might be time to return—and remember.