Biden, Democratic Party losing support among Black voters as concerns about economy spike: Poll

Janelle King and Jason Brown discuss Biden's slipping support from Black voters and how candidates can capitalize on issues important to Black Americans.

The Atlantic went to bat for President Biden, publishing a piece Wednesday titled "Why Americans Hate a Good Economy" as his polling continues to show overwhelming disapproval.

The article began by citing a recent Financial Times poll showing the majority of voters saying they are financially worse under Biden "despite some objective positive measures" like 3.9% unemployment, an unchanged consumer price index and a drop in "wage inequality."

Staff writer Jerusalem Demsas attempted to explain what she viewed as the disconnect between Americans' perception of the economy versus the economy itself, highlighting "seven possible explanations."

The Atlantic offered seven explanations as to "why Americans hate a good economy" as President Biden's polling continues souring. (Kent Nishimura/Getty Images)

The first is "People need a second to adjust," reflecting that the country is still bouncing back from the COVID pandemic followed by the spike in inflation.

"Although price jumps are leveling off, it’s important to appreciate that economic conditions changed really fast in both directions, and people may need time to register what’s going on," Demsas wrote. "Even if respondents think conditions are improving, they’re rating the Joe Biden Economy based on the past two years, not just last month, and their perceptions may be baked in."

The second reason, Demsas conceded, is that "inflation is just really that bad," writing "If someone has a good-paying job in an inflationary environment, they may tell a pollster that they’re doing well—but the economy is doing poorly."

BIDEN SKIPPING PUBLIC BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION TO NOT CALL ATTENTION TO AGE, NY TIMES REPORTER SAYS

The third explanation is that "expectations are high."

"During the pandemic, the federal government provided Americans unprecedented support. It stopped evictions; it dropped thousands of dollars into personal bank accounts; it paused student-loan repayments; it gave aid to unemployed workers; it provided tax breaks to parents of young children, and billions in aid to state and local governments. In doing so, the government may have raised expectations for what a ‘good economy’ is supposed to feel like," Demsas wrote. "In 2020 and 2021, Americans acquired new sources of income, which have since disappeared. If I found $10,000 on the ground one year, and was not so fortunate the next, I would be correct in telling a pollster that I’m worse off, even if I got a $5,000 raise."

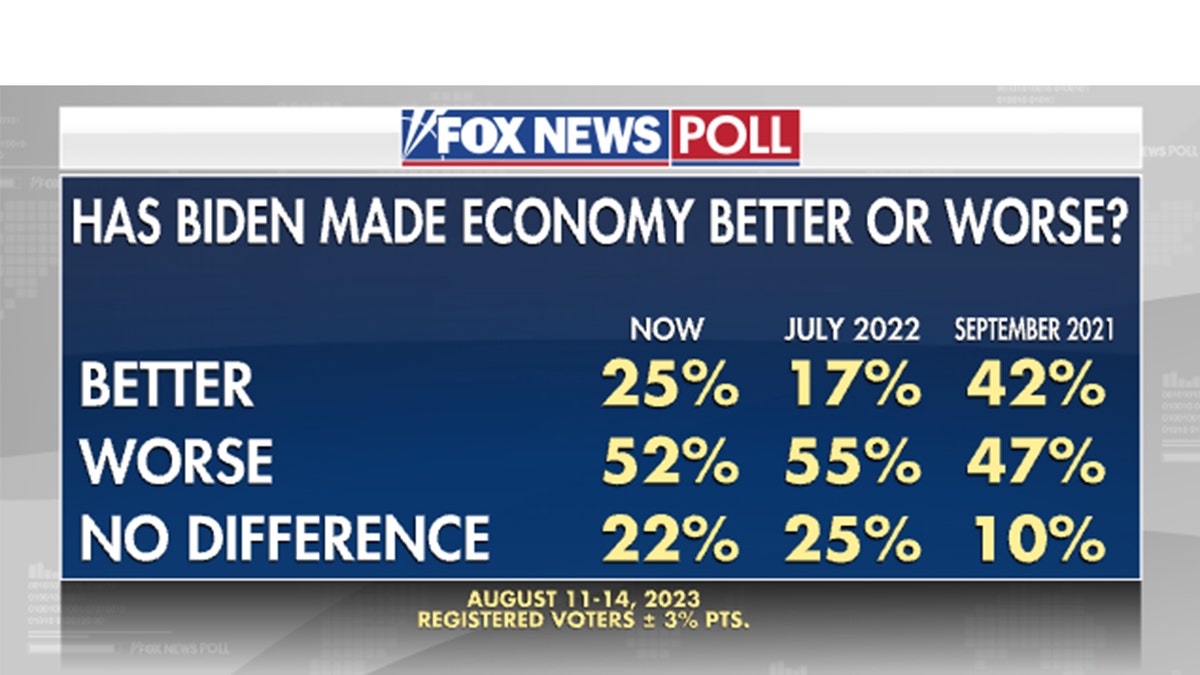

A Fox News poll from August showed more than half of Americans believe President Biden has made the economy worse. (Fox News)

After acknowledging that "rent is too damn high," the Atlantic staff writer went on to say, "The biggest winners are at the bottom."

"A new study showing declining inequality found that Americans whose incomes rank in the bottom 10 percent have seen their inflation-adjusted wages rise to new heights since the pandemic," Demsas told readers. "Although in absolute terms, high-income people are doing better than low-income people, they may be more sensitive to the "costs" of a tight labor market."

BILL MAHER SAYS DEMS' LAST-MINUTE SAN FRAN CLEAN-UP FOR XI IS A SIGN THAT ‘TRUMP IS WINNING’ IN 2024

Demsas then turned to blame the media loving "bad news" as the sixth explanation, quoting Biden's own criticism of "negative" reporting about his administration.

"The media does have a negativity bias, which has some effect on how Americans perceive the state of the world. But when people are asked about the amount of negative or positive news they’ve heard about the economy, survey responses look relatively stable since 2020," she wrote.

The RealClearPolitics average of polls show only 38% approve of President Biden's handling of the economy. (AP/Jonathan Ernst/Pool)

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The last explanation, according to Demsas, is that Democrats are "bad cheerleaders."

"Beyond the question of why Americans’ feelings about the economy may have diverged from the actual economy is another, perhaps equally important question: Why are policy makers and commentators so eager to explain it—or explain it away?" Demsas wondered. "I attribute all of this energy to a mad dash to set the narrative following the pandemic recession. Some believe that the government’s robust response to the crisis proves that we could stabilize working- and middle-class family finances in perpetuity. Others believe that ensuing inflation was too high a price to pay for those social supports. Yet others wish that policy makers would focus more on how their ideas and victories are translated through a fragmented media ecosystem."

She continued, "Narrowly, this debate is about whether voters think the economy is good or bad, and why; the bigger issue is what lesson future politicians will draw about how to respond to recessions. Will they cower at the potential inflationary effects of fiscal stimulus? Will they require that any new social supports remain permanent rather than risk voters’ wrath when they are removed? Policy makers tend to overlearn the lessons from the last war, and every side is fighting to say what, exactly, those lessons are."