You have to tell the government what you're going to fish for: Meghan Lapp

Seafreeze Fisheries liaison Meghan Lapp and attorney Mark Chenoweth tell 'The Story' how a case brought by fisherman could change the regulatory authority of the federal government.

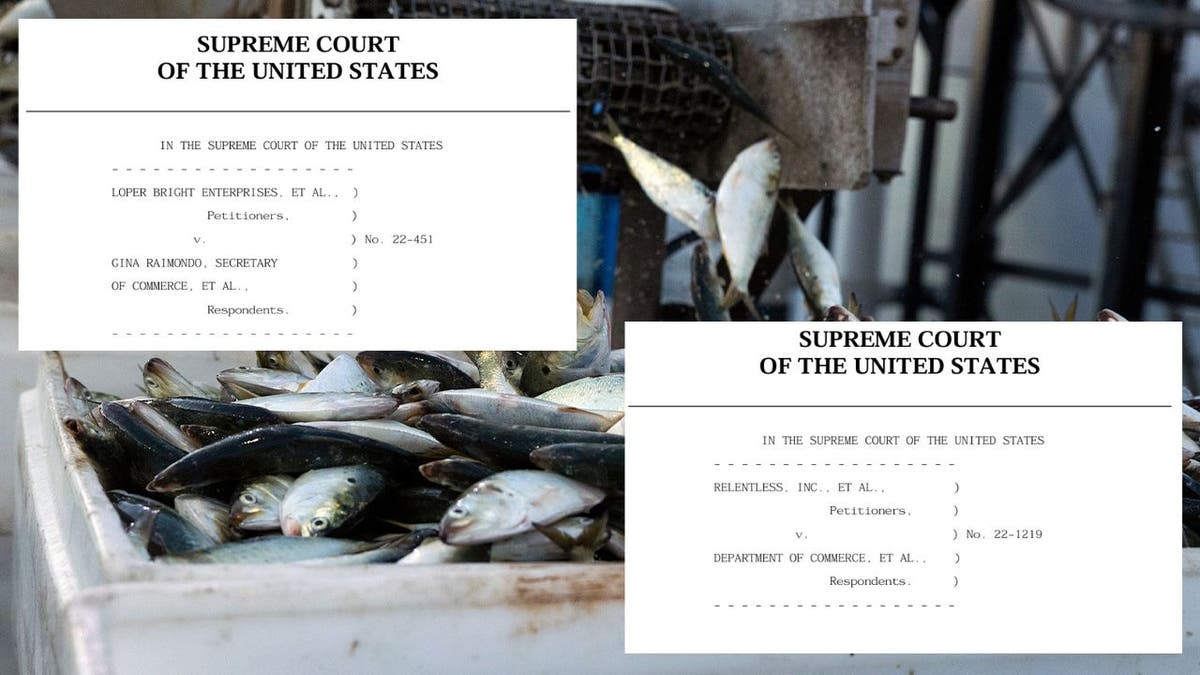

The Supreme Court heard oral arguments Wednesday in the Loper Bright Enterprises, Inc. v. Raimondo and Relentless, Inc. v. Dept. of Commerce cases that could see a longstanding 1984 precedent overturned.

The plaintiffs in the Loper Bright Enterprises, Inc. v. Raimondo case are a group of herring fishermen from Cape May, N.J., who are challenging a 2020 regulation issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service that requires them to pay around $700 per day for human monitors to be put on their boats when asked to ensure they adhere to fishing regulations.

Plaintiffs in the Relentless, Inc. v. Dept. of Commerce case are a group of Rhode Island fishermen who are challenging the 1984 Chevron precedent as well as the 2020 regulation.

The New Civil Liberties Alliance (NCLA), a nonprofit civil rights organization, is representing three fishing companies: Relentless Inc., Huntress Inc. and Seafreeze Fleet LLC.

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments Wednesday in the Loper Bright Enterprises, Inc. v. Raimondo and Relentless, Inc. v. Dept. of Commerce cases.

The Cause of Action Institute, a nonprofit organization that advocates for government accountability, is representing the plaintiffs in the Loper Bright Enterprises, Inc. v. Raimondo case.

For the past 30 years, the Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) has given the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) the authority to require monitors on commercial fishing boats, according to the Cause of Action Institute.

"The MSA explicitly requires the owners of certain classes of fishing boats to pay for their own monitors. However, the MSA does not specify who is responsible for paying the cost of the monitors on the herring boats used by the fishermen," the organization stated.

"The issue began when the government recently ran out of money to pay for certain at-sea monitoring programs. Instead of asking Congress for more money, NOAA suddenly decided that the herring fishermen must now pay for the cost of third-party monitors."

Fishermen prepare to offload catch from fishing vessel Brianna Louise at Lund's Fisheries Inc. in Cape May, New Jersey, U.S., on Tuesday, Oct. 17, 2023. (Photographer: Rachel Wisniewski/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The nonprofit organization added that the monitoring costs can take up as much as 20% of a ship’s daily take-home pay and "presents a huge burden that could easily drive these fishermen out of the herring business."

A 1984 Supreme Court case, Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, found that when a law is "ambiguous or silent about what is required in a specific situation, federal courts must defer to regulatory agencies," the Cause of Action Institute noted.

"On a daily basis, before you leave the dock, you have to tell the government what you're going to fish for. You have a government ankle bracelet on your boat called Vessel Monitoring System. They know where you are at all times. They know how fast you're going, what direction you're going in," said Meghan Lapp, the fisheries liaison for Seafreeze Ltd.

HIGH-PROFILE SUPREME COURT CASES TO WATCH IN 2023–24

Lapp told "The Story" Wednesday they are required by Congress to take fisheries observers on their boat.

Fishing vessel Eva Marie, one of several boats named in the Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo Supreme Court case, prepares to dock at Lund's Fisheries Inc. in Cape May, New Jersey, U.S., on Tuesday, Oct. 17, 2023. (Photographer: Rachel Wisniewski/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

"They collect fisheries data as well as enforce rules and regulations. We can be boarded by the Coast Guard at any time, with or without cause, and this is all going on while we're harvesting fish. We're hauling back nets. We're using heavy equipment, you know, on a platform that's moving," she added. "Going fishing is a dangerous profession, but it's also an extremely rewarding one, but in this particular instance, the government decided that it wanted to expand its monitoring program, but Congress didn't give it the money to do so. So, the agency's solution was to force those costs on us."

Mark Chenoweth, president and chief legal officer of the NCLA, told anchor Martha MacCallum that Congress never said agencies could charge Lapp and others to put monitors on their boats, nor were they given the authority to do so.

"The agency didn't have enough money to do it unless they charged the boats," he said. "And so, they decided to read the regulation in a way favorable to the government, so that they could go ahead and put more monitors on the boats than Congress approved."

Catch is offloaded from a fishing vessel at Lund's Fisheries Inc. in Cape May, New Jersey, U.S., on Tuesday, Oct. 17, 2023. (Photographer: Rachel Wisniewski/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Justice Neil Gorsuch appeared skeptical during oral arguments about the Chevron ruling, saying he has concerns about its impact on people who have "no power to influence agencies."

"The cases I saw routinely on the courts of appeals — and I think this is what niggles at so many of the lower court judges — are the immigrant, the veteran seeking his benefits, the Social Security Disability applicant, who have no power to influence agencies, who will never capture them, and whose interests are not the sorts of things on which people vote, generally speaking," Gorsuch said.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

He added: "[I] didn’t see a case cited, and perhaps I missed one, where Chevron wound up benefiting those kinds of peoples. And it seems to me that it’s arguable, and, certainly, the other side makes this argument powerfully, that Chevron has this disparate impact on different classes of persons."

The Supreme Court is expected to issue rulings in late June or early July.