After more than a century and a half in Mexico, the remains of U.S. soldiers killed during the Mexican-American War will be returned to the United States on Wednesday.

The long deceased troops will receive full military honors during a repatriation ceremony set to take place at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. The bodies will then be handed over to forensic anthropologists in the hope of determining who the soldiers were or, at the very least, what state they came from.

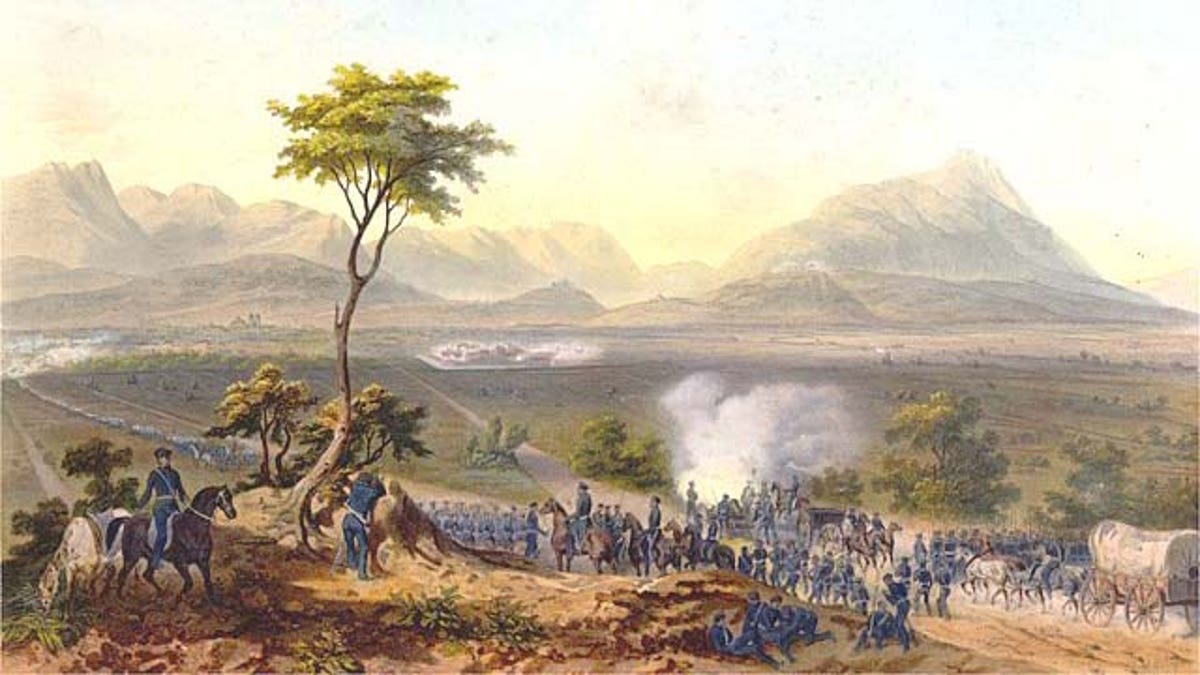

The soldiers were part of the Army of Occupation led by former President Zachary Taylor – then a general – who fought in the 1846 Battle of Monterrey. Out of a force of more than 6,000 soldiers from Tennessee, Mississippi, Ohio and Texas, only 120 U.S. troops were killed and 43 went missing in the three day mêlée in which American forces defeated the Mexican Army of the North.

Archaeologists in Mexico discovered the remains of 10 soldiers between 1995 and 2011 as the scientists dug in an area where a construction company planned to build.

Since the discovery, the U.S. State Department and members of Tennessee’s congressional delegation have negotiated with the Mexican government to have the remains returned to the U.S. Tennessee believes the soldiers were part of the state’s militia. About 30,000 Tennesseans responded to calls for additional troops and about 35 were killed in action, according to the Tennessean.

- Best pix of the week

- Guinness Records, Mexico’s Favorite Pastime

- Digital X-rays give look inside holy reliquaries in Mexico

- Borinqueneers: Puerto Rico’s Forgotten Heroes

- Police, soldiers swarm Mexico’s Acapulco, killings continue

- Borinqueneers get recognition they deserve by U.S.

- Border Fence Would Cut Through Texas University

- Cemetery In Mexico Holds Remains Of 750 U.S. Soldiers Killed During Mexican-American War

- U.S. Military Cemetery in Mexico City

- Explorers Find 200-Year-Old Shipwreck in Gulf of Mexico

“After working for several years with the State Department and our U.S. consulate in Monterrey, Mexico, I was pleased to learn that the remains of these U.S. soldiers will finally be returned to American soil,” Rep. Scott DesJarlais of Tennessee said in a statement. I applaud the diligent work and dedication of our State Department and military personnel who have worked tirelessly over the years to secure the return of these remains.

DesJarlais added: “This joint effort embodies the longstanding commitment to our men and women in uniform that the United States does not leave our fallen soldiers behind.”

A team of scientists led by Hugh Berryman, a forensic anthropologist and a professor at Middle Tennessee State University, will work with the Army in an attempt to identify the solders and find out more about their life and how they died.

While scientists are hopeful that the skeletal remains of the soldiers are in good condition, they warn that it will be very difficult to determine exactly who each solider is unless a descendent of one of the veterans comes forward or DNA can be extracted from the teeth.

“If the skull is in good condition you may be able to do facial reconstruction or if the teeth are in good condition the DNA can be extracted to find out of there is a relative,” A. Midori Albert, a professor and forensic anthropologist at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, told Fox News Latino. Albert is not one of the anthropologists working with the Army.

“You really need a living descendent to accurately determine the identity of the solders,” she said.

Albert added, however, that while it may be difficult to determine exactly who these soldiers are, there is still a wealth of information that can be gleaned from the skeletal remains. Bone measurements and comparisons to similar remains can determine if the soldiers are actually from the U.S. and what their age was when they died.

Anthropologists can also look at any bone trauma the soldiers had to determine how they died and if disease played a part in their death. Some of the bones had greenish stains, suggesting they had been in long contact with metal, possibly from the bullets that took their lives.

New technology using stable isotopes found in bones might even be able to determine where in the U.S. these soldiers came from.

“Just getting an age range and how they died is very important because it can confirm historical facts,” Albert said. “Evidence always backs up stories.”

The Mexican-American War lasted from 1846 to 1848 and led to the United States adding territory that would later become Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. The war also helped Taylor become president in 1849 – he died suddenly in office of a stomach-related illness a year later – and was a training ground for many of the military leaders during the Civil War a decade later, including Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

While the identity of these soldiers may be difficult to determine, Albert said that many people will be happy to know that they come from a region that has had an impact on U.S. history.

“A lot of people enjoy being from a region that did something for our homeland,” she said. “If this is anything it acts as human comfort.”