Among the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, America's first African-American military air squadron which heroically fought in World War II, was a little known about Hispanic pilot named Esteban Hotesse.

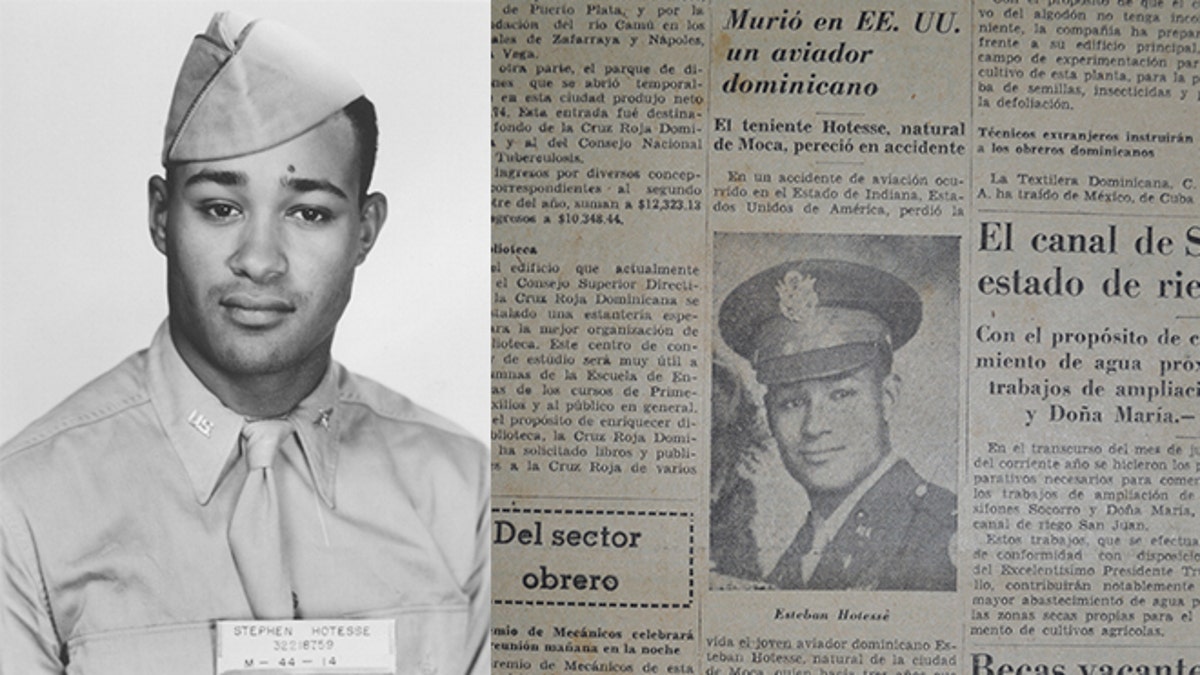

Born in Moca, Dominican Republic, but a New Yorker since he was 4 years old, Hotesse served with the Tuskegee Airmen for more than three years before he died during a military exercise on July 8th, 1945. He was just 26.

As a black Dominican, Hotesse was a part of a squadron credited for single-handedly tearing down the military's segregation policies, while helping to change America's perception of African-Americans during the Jim Crow era.

He is believed to be the first Dominican soldier to serve on the well-known squadron. His historic role was recently discovered by a group of New York academics.

Enlisted on February 21, 1942, Hotesse was part of the 619 squadron of the 477 bombardment group known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Though his squadron never flew in combat, he took part in the battle for civil rights at home.

Hotesee took part in what is known as the Freeman Field Mutiny. In 1945, Hotesse and the rest of the Tuskegee airmen attempted to integrate an all-white officers club at the airfield base in Seymour, Indiana. Under military regulations, any military officer clubs were open to any officer regardless of race, but Freeman Field segregated black from white officers. More than 100 black officers of the Tuskegee group were arrested when they defied orders and sat in the white club anyway. It wasn't until 1995 that the record of their reprimands was expunged.

Not only were they pioneers, in U.S. aviation, as black members of the U.S. armed forces — they were pioneers in the Civil Rights movement.

Hotesse's contributions as an American pioneer - underscoring the importance of Hispanic servicemen and women during our nation's greatest war - would have gone unnoticed had it not been for 29-year-old Edward De Jesus. An academic working part-time as a researcher at the Dominican Studies Institute at CUNY, De Jesus, like Hotesse, was born in the Dominican Republic and moved to the United States at the age of 4.

“I had never heard or read about Dominicans in World War II,” De Jesus, 29, said. “It’s significant for me because growing up looking at American history documentaries it was always hard to identify because you never see someone like you in these documentaries.”

De Jesus uncovered Hotesse's story while helping a team of researchers working on a three year project about the role of Dominicans in the war effort. He dug through and found his census records, naturalization form and marriage certificate, and eventually came in contact with Hotesse's relatives.

Hotesse was survived by his Puerto Rican wife Iristella Lind Hotesse, with who he had two daughters: Mary Lou and Rosalie Hotesse. One of his granddaughters, Iris Rivera, donated a collection of photos and articles to the Dominican Institute.

"The family was waiting for this moment, for him to be recognized," De Jesus said.

Hotesse's story is among 10 on display at an exhibit at the Dominican Institute honoring Dominican veterans and their contributions during World War II.