MEXICO CITY – The two-minute video started with a casting call and a chance at winning an invitation to the Instituto Cumbres graduation – the social event of the year at one of Mexico City most expensive schools. It went on to feature five male students auditioning models, who dance, flirt and wash their feet – all as the boys sip liquor, look disinterested and tend to a jaguar on a leash.

The video went viral in Mexico, offering a rude reminder of the insensitivities of the upper crust in a country where half the population is poor, social mobility is scant and political connections can count for more than talent job competitions. It also offered a glimpse at the attitudes of the country’s future leaders – a frightening prospect for many columnists and commentators.

“What message did they want to give everyone? Basically that they have lots and lots and lots of money. And that’s why they absolutely don’t care what any of us thinks of them,” columnist Susana Moscatel wrote in the newspaper Milenio. “The sad thing in all of this is that it is precisely the prototype of boys that will end up as political party leaders or other variations of that and keep the party going.”

The scandal once again brought attention to the mirrey phenomenon, in which children of the elites, enabled by social media and society magazines, are increasingly accused of exhibitionism and flaunting their power, privilege and possessions – in ways that exceed the excesses of the entitled generations of “juniors” coming before them.

The word, “Mirrey” – “My king” – began as a greeting in the Lebanese community, but came to describe young men of privilege prone to partying, wearing their shirts unbuttoned and showing off status – with crooner Luis Miguel seen as the model mirrey.

“It was clear by 2007 that you have a new urban tribe,” says author and academic Ricardo Raphael, who recalls, “I heard my kids talking about the smell of ‘mirrey’ after a party.”

Raphael started investigating the subject at around the same as the hit Mexican movie Nosotros los Nobles was released in 2013. It featured a rich father tricking his indolent children into thinking that family fortune evaporated in bankruptcy to teach them about the real world.

The movie, Rafael told Fox News Latino, showed “this guy, who is not an adult, he’s between 17 and 30 years old, spoiled kid (and) good for nothing. … When I started looking at what was going on with the Mexican elite, I found these people.”

He calls current age and the rise of mirreyes, “The Mirreynato,” or “Mirrey rule,” in which money is the main value, while impunity is the norm.

“The mirrey doesn’t belong to another urban tribe: he aspires to be the chosen tribe, which places itself above all others,” Raphael writes in his recently released book Mirreynato, The Other Inequality. The juniors of past years – whose exhibitionism was kept in check by the elites’ origins in the political regime coming out of the Mexican Revolution – were arrogant, Raphael says, “But today it’s become more notorious, the same with impunity, corruption, discrimination and inequality.”

The rise of the mirreyes is causing disquiet in Mexico, where they’re seen as the heirs to a country still struggling with issues such as inequality, impunity and discrimination – and addressing the deep disenchantment with the transition to democracy over the past three decades.

Their ascendance is seen in society magazines – which have mushroomed in Mexico over the past 15 years, as the nouveau riche show off and the old money types try stay in the status seeking game – and on social media sites such as Instagram and Facebook.

The motives are more than mere vanity, Raphael says, “because people are going to protect you if you show off.”

He gives examples such as police officers not pulling over cars traveling in convoys with heavy security.

Friends with the rights connections, meanwhile, can lead to jobs and contracts later in life – and possibly riches.

“Friends and family [in Mexico] substitute for a rule of law that works,” says Manuel Molano, deputy director of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, a public advocacy think tank. “Among friends, it’s easier for you protect each other or become accomplices.”

Such friendships are often formed as schools such as Instituto Cumbres – an academy belonging to the Legionaries of Christ, a Catholic order founded in Mexico and famed for courting the rich. (Its founder, Father Marcial Maciel, died in disgrace, having fathered children and been accused of sexually abusing seminarians.)

These schools perform only slightly better than public schools on standardized tests, according to Raphael, but offer parents the opportunity to have their children befriend the offspring of elite families.

“It’s not so much the academic level, rather they bring together the children of very prominent people,” said Bernardo Barranco, a commentator of Catholic matters, who describes the Legionaries of Christ’s institutions and schools as “clubs.”

Barranco sees a change in the elites as the old money is joined by the new money made by politicians, union bosses and possibly even narcos. “They don’t have the culture of work that the old generations of rich people in Mexico did,” he said.

For those lacking the social connections, there are attempts at mimicking the mirreyes.

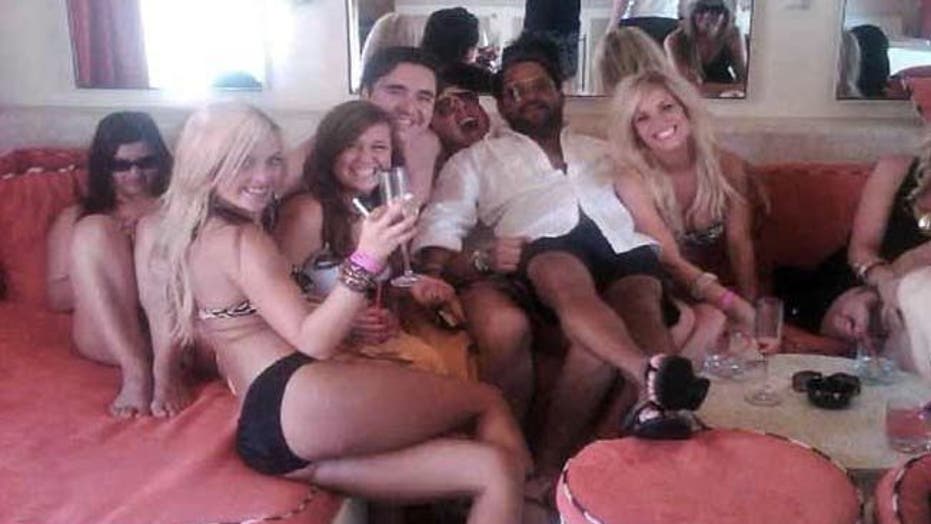

“There is the ‘mirrey’ that has had money all of his life and the ‘wannabe,’” said Pepe Ceballos, founder of the website, Mirrreybook, which posts photos of mirreyes – many of which are submitted by mirreyes themselves – at the beach, in nightclubs and, increasingly, on private planes. “They’re the same. It’s a person that has this need for you to see them, whose personal value is in these valuables.”

The need to show status stretches through society, say some observers, who question if the mirreyes are not a symptom of something societal in Mexico.

“The graduation parties of the middle and upper classes and the quince años of the popular classes,” analyst Genaro Lozano wrote in the newspaper Reforma, “both are rituals of a society enamored with simulation, spending and status anxiety.”