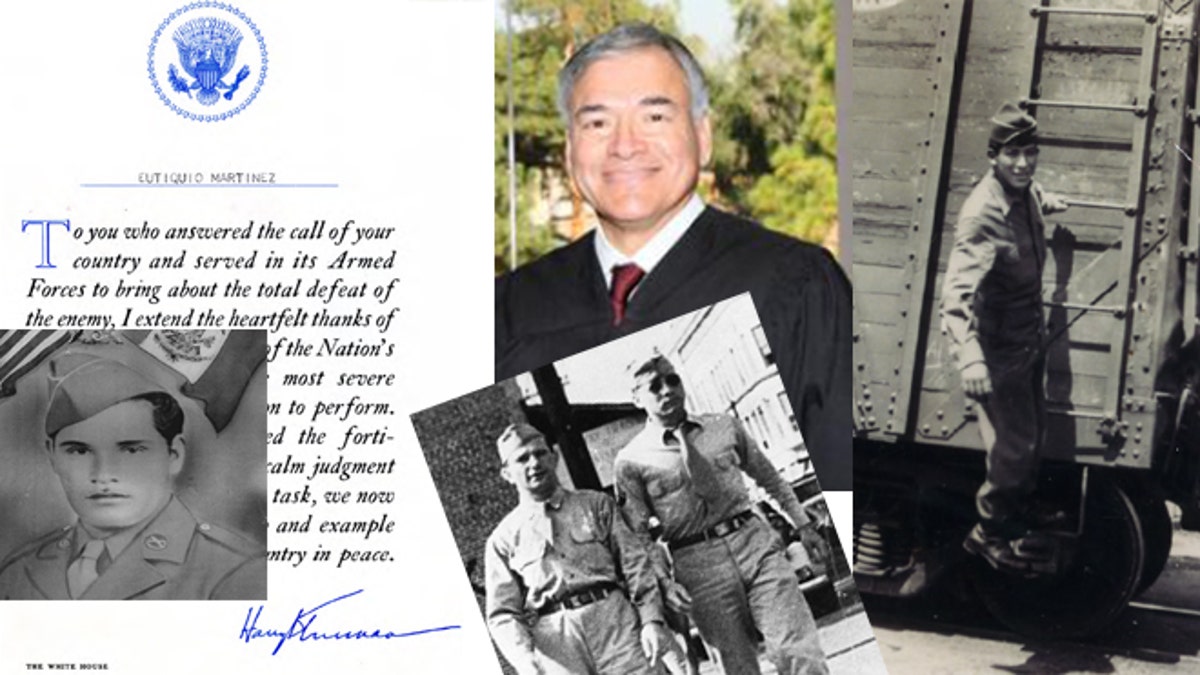

Judge Frederick Aguirre (center) surrounded by, clockwise from right, his uncle Richard Aguirre as a P.F.C.; his father Alfred Aguirre with Ruben Abraham in 1945; his father-in-law, Eutiquio Martínez, along with a letter to Martínez from the White House and signed by Harry S. Truman. (Photos: Courtesy Orange County Hispanic Bar Association, American Patriots of Latino Heritage)

California Superior Court Judge Frederick P. Aguirre knows that he was only able to attend college at University of Southern California and law school at University of California at Los Angeles because he was able to attend Orange County public schools that had been integrated.

He knows that the schools were only integrated because of the newfound political power that returning servicemen had in Southern California in the post-World War II period.

He knows that because his father, Alfred, uncles Richard and Joe, and 23 assorted cousins all served in the U.S. military during World War II, along with another 6 cousins in Korea.

“My family nobly served in Germany, Italy, North Africa, the Pacific, as well as the Air Force, Navy, Army—all the services,” Aguirre told Fox News Latino.

“I carry it with me—the fact that they provided me with every opportunity I’ve had,” he added.

Fifteen years ago, just a couple of years before Gov. Gray Davis appointed Aguirre to the Superior Court of Orange County, Aguirre and his schoolteacher wife, Linda Martínez Aguirre, started a small non-profit organization called Latino Advocates for Education, with the mission of documenting the contributions of Latino servicemen in the U.S. military.

Along with an engineer friend, Rogelio Rodriguez, they have “personally profiled thousands of veterans,” Aguirre said, laughing. “All while being a full-time judge, schoolteacher and engineer.”

Part of the problem, he pointed out, is that before Vietnam, Latinos were listed as white by the armed forces. So the three of them ended up going through more than 20 million names of soldiers who served during World War II and Korea, extracting those with Hispanic surnames.

They have discovered around half a million Latinos who were counted as white and have attempted to track their rank, medals received, casualty figures and so on, for each.

“This has been a tough job, because we did it without funding,” Aguirre told the bilingual Southern California magazine, Para Todos ("For Everybody'), in 2011. “It was all volunteer work on our own time.”

Aguirre is the grandson of a Mexican migrant who settled in Orange County in 1908.

His father, Alfred, was a 9th-grade dropout who trained as a radio operator with the Army.

When he shipped out, he became part of the Army Corps of Engineers unit that built Kadena air field in Okinawa after the Japanese island was taken over by the U.S.—an invasion, by the way, that Aguirre’s uncle, Richard, took part in.

“From my uncle's company of 200 men, only 20 came back alive and uninjured,” Aguirre said. “He didn’t suffer one scratch at Okinawa. He became a sergeant at West Point after the war.”

Aguirre points out that for Mexican-American families in Southern California, it was a point of patriotism and pride to take up their country’s call to arms.

“My wife’s father and five of her uncles served in World War II and Korea,” he told FNL. “In my family, there are two sets of five brothers who all served. There’s one family here, Nevarez is their name, in which 8 brothers served. How many parents have eight kids, let alone eight boys, let alone born close enough together to serve within 10 years of each other?”

He points out that because they were classified as white, many of their achievements aren’t known.

“We have identified more than 600 Latino flyers during World War II,” he said, “including five aces who downed more than five enemy airplanes. Did you know that the first person to be killed at Pearl Harbor was Latino? Ensign Manuel Gonzalez, who was trying to land his plane when the attack happened.”

Aguirre points out, “I didn’t see that in ‘Pearl Harbor’ or in ‘Tora! Tora! Tora!’ did you?”

After returning from war, many of those servicemen, now accustomed to receiving the same treatment as white soldiers, couldn’t understand why they couldn’t use the same swimming pools or movie theaters as white patrons.

Even more important, their kids were expected to attend separate schools. Aguirre’s father, who worked in construction the rest of his life, joined the fight to integrate Orange County schools, eventually becoming the first City Councilman in Placentia, Calif.

He and his wife put every one of their seven children through college.

In Aguirre’s chambers, visitors can spot photos of his relatives during the war, Para Todos reported, as well as a large Stars and Stripes.

“The flag was given to me by my cousin, Sgt. Christopher Miranda Braman,” who was stationed at the Pentagon during the 9/11 attacks, he said, and personally helped 62 people flee the building. “It fills me with pride to have someone in my family who is a hero as he is.”

Earlier this month, the U.S. Congress awarded the 65th Infantry Regiment, a Puerto Rico-based unit known as the “Borinqueneers,” the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award this side of a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Was Aguirre pleased by the honor?

“Of course,” he told FNL. “Immediately, I sent a note congratulating my friend, [Supreme Court Justice] Sonia Sotomayor, saying, ‘How great, Boricua!’”