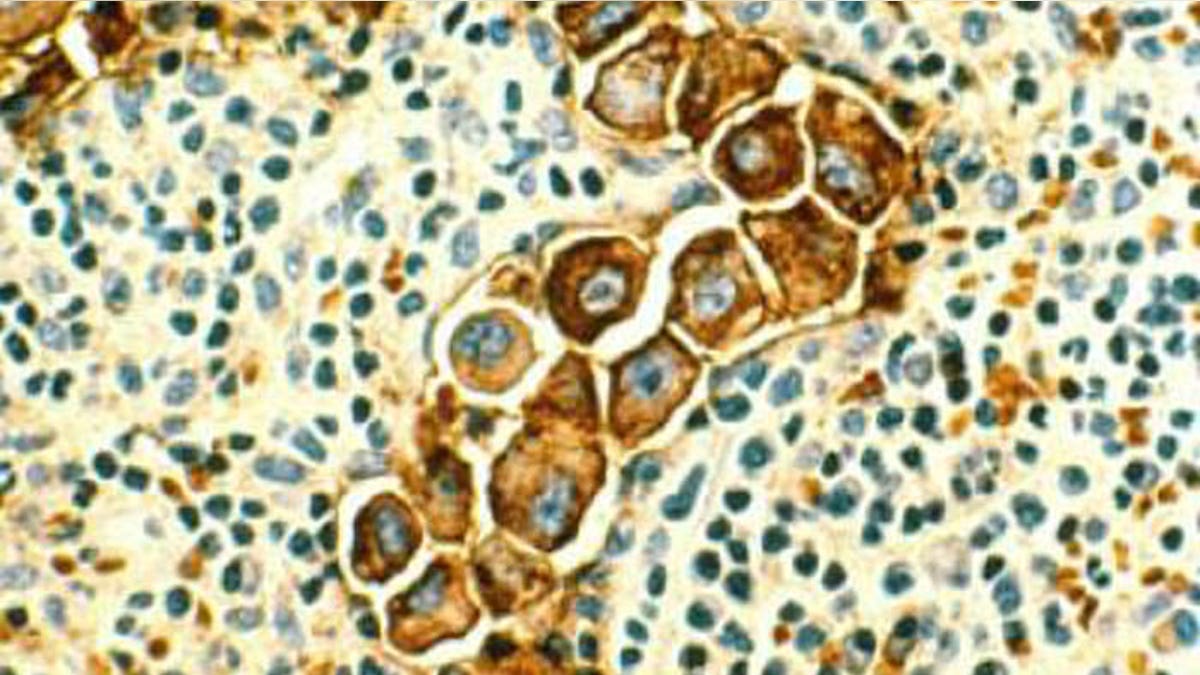

This image shows metastasized human breast cancer cells (magnified 400 times, stained brown) in lymph nodes. (National Cancer Institute)

The proportion of people surviving years after a cancer diagnosis is improving, according to a new analysis.

Men and women ages 50 to 64, who were diagnosed in 2005 to 2009 with a variety of cancer types, were 39 to 68 percent more likely to be alive five years later, compared to people of the same age diagnosed in 1990 to 1994, researchers found.

“Pretty much all populations improved their cancer survival over time,” said Dr. Wei Zheng, the study’s senior author from Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

As reported in JAMA Oncology, he and his colleagues analyzed data from a national sample of more than 1 million people who were diagnosed with cancer of the colon or rectum, breast, prostate, lung, liver, pancreas or ovary between 1990 and 2010.

Among people ages 50 to 64 diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer in 1990 to 1994, about 58 percent were alive five years later. Five-year survival rates were about 83 percent for breast cancer, about 7 percent for liver cancer, about 13 percent for lung cancer, about 5 percent for pancreas cancer, about 91 percent for prostate cancer and about 47 percent for ovarian cancer.

Among people in the same age range diagnosed between 2005 and 2009, a larger proportion survived each of the cancers except ovarian cancer. Survival rates at five years rose by 43 percent for colon or rectum cancers, 52 percent for breast cancer, 39 percent for liver cancer, 68 percent for prostate cancer, 25 percent for lung cancer and 27 percent for pancreas cancer, compared to the early 1990s.

The better odds of survival did not apply equally to all age groups, however, and tended to favor younger patients. For example, survival rose by only 12 to 35 percent for people diagnosed between ages 75 to 85.

And while there was a small improvement in ovarian cancer survival among white women during the study period, survival among black women with ovarian cancer got worse.

Advances in treatments and better cancer screenings and diagnoses are likely responsible for the overall increases in survival, the researchers write.

“In general our study shows different segments benefit differently from recent advances in oncology,” Zheng said. “We need to find out the reason.”

The researchers speculate that older people may not benefit equally from medical advances, because doctors may avoid aggressive care for them for fear they couldn't tolerate treatments like surgery or chemotherapy.

Also, older people and racial minorities are less likely to be included in trials of new cancer treatments, the researchers point out. They say more effort should be made to include those groups in trials so doctors have treatment guidelines based on science.

“Additional research is needed to find the reasons why there are gaps,” Zheng said.